pomponazzi pietro grataroli guglielmo (1 Ergebnisse)

Produktart

- Alle Produktarten

- Bücher (1)

- Magazine & Zeitschriften

- Comics

- Noten

- Kunst, Grafik & Poster

- Fotografien

- Karten

-

Manuskripte &

Papierantiquitäten

Zustand

- Alle

- Neu

- Antiquarisch/Gebraucht

Einband

- alle Einbände

- Hardcover

- Softcover

Weitere Eigenschaften

- Erstausgabe

- Signiert

- Schutzumschlag

- Angebotsfoto

Land des Verkäufers

Verkäuferbewertung

-

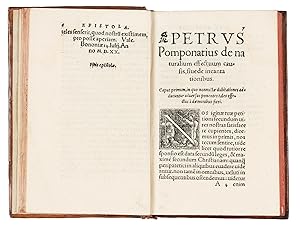

De naturalium effectuum causis, sive de Incantationibus, opus abstrusioris philosophiae plenum, & breuissimis historijs illustratum atque ante annos XXXV compositum, nunc primà m verà in lucem fideliter editum. Adiectis brevibus scholijs à Gulielmo Gratarolo Physico Bergomate

Verlag: Basel, Heinrich Petri August 1556, Basel, 1556

Zustand: Molto buono (Very Good). 8vo (152x96 mm). [16], 349, [3] pp. Collation: ?8 A-Y8. Large printer's device on last leaf verso (below which a contemporary hand has added the Psalms quote: ?[?] Tange montes et fumig[abunt]?). Woodcut historiated initials on black ground. 18th-century marbled calf, gilt spine with five raised bands and lettering piece, red edges (restorations to spine and joints). On the front pastedown engraved bookplate of Henry Blackett with his family's coat-of-arms and the motto ?nous travaillons en espérance? (possibly the London publisher Henry Blackett, 1825-1871). Skillfully repaired worm track to the lower margin at the beginning and at the end of the volume not affecting the text, round worm hole in the lower blank margin throughout most of the volume, pale damp stain to the upper outer corner of the first and last leaves, otherwise a very good, clean copy with several reading signs and marginal annotations in Latin (slightly trimmed) by a contemporary hand. RARE FIRST EDITION of the De incantationibus (?On incantations?), the only work by Pietro Pomponazzi included in the Index of forbidden books (first in the 1580 Parma index, then in the 1596 Roman one) and a true landmark in the history of philosophy. The work takes its cue from a question posed by the Mantuan physician Ludovico Panizza regarding the explanation of some miraculous events (two seriously ill kids and a man wounded with an arrow healed with spells and a flour sieve moved only by the sound of words) and the existence of demons. Always remaining within the frame of the Aristotelian philosophy, the work firmly rejects all magical cures and events, while supporting a physical explanation of all magical phenomena in direct controversy with the demonological and astrological literature of the time, which in the same years was fuelling the witch-hunt. By bringing everything that is in the world under the general laws of nature, the De Incantationibus comes to the conclusion that there is no such thing as magic, witchcraft, miracles, etc., as all marvelous events and powers observed in experience or recorded in history have their natural explanation. ?In regard to the religious issue, I have tried to show that he [Pomponazzi] makes a claim for the absolute truth of philosophy and relegates religion to the purely practical function of controlling the masses. Religious doctrines contain a kind of truth because they can persuade men to act so as to preserve the social order. But religious doctrine has social value rather than speculative veracity [.] rational truth is the only truth. It is really compatible only with complete disbelief. And I think that this is the statement that Pomponazzi makes. The only doctrines that he accepts are those of philosophy. Philosophy rejects the personal Christian God acting within history and eliminates the miracles of religion. Philosophy reduces to the absurd the notion of a life after death. And finally philosophy destroys revelation itself by viewing it as the product of heavenly forces rather than the act of divine will? (M.L. Pine, Pietro Pomponazzi Radical Philosoper of the Renaissance, 1986, pp. 34-35). The De Incantationibus is together with his treatise on the immortality of the soul Tractatus de immortalite animae, first published at Bologna in 1516, probably Pomponazzi's most important and influential achievement, as it constitutes a forerunner of naturalism and positivism. In the De Incantationibus ?Pomponazzi's conclusion results from a dramatic change in method which in turn is based on a profoundly new attitude toward philosophical inquiry. Medieval theologians and philosophers as well as most Renaissance thinkers were content to limit the role of reason in nature because they sincerely believed that the Christian God intervened in the natural order to create miraculous occurrences. As we have seen, this belief prevented their scientific convictions from destroying Christian doctrine by exempting central Biblical miracles from natural process. Even those who held that Christian revelation and Aristotelian science were irreconcilable maintained a sincere fideism which allowed each universe to remain intact, each standing separate from the other. But once Pomponazzi applied the critical method of Aristotelian science to all religious phenomena, Christian miracles were engulfed by the processes of nature. Absorbed by the ?usual course of nature', the miracle could no longer be the product of divine fiat. Indeed Christianity itself became merely another historical event, taking its place within the recurring cycles of nature, and destined to have a temporal career within the eternal flow of time? (Pine, p. 273). The text, which had a tormented elaboration and the author never considered concluded, was composed in 1520 (the preliminary epistola to Panizza is dated Bologna, 24 July 1520) and circulated widely in manuscript form until it was published posthumously in 1556 (and again in 1567) by the Protestant physician, alchemist and editor Guglielmo Grataroli. Guglielmo Grataroli (or Gratarolo or Gratarol) was born at Bergamo. After completing his medical studies in Padua, he returned to his native city to practise medicine. In 1546 he underwent a conversion to Protestantism and after suffering persecution by the local inquisition he fled to Basel, where he practised as a physician and taught at the university. In 1552 he published an unusual pamphlet in which he expressed his own religious beliefs, including a millenarian admonition to the fauthful (Confessione di fede, con una certissima et importantissima ammonitione). He entered in contact with Calvin in Geneva and associated with printing circles in Basel and Strassburg. He compiled an index to the Basel edition of Galen's works and produced a number of small tracts on medical topics intended to constitute a sort of self-help encyclopedia for educated laymen. But Grataroli is also remembered as the maker of his compatriot's, Pietr.