What warps when you're traveling at warp speed?

What's the difference between a holodeck and a hologram?

What happens when you get beamed up?

What's the difference between a wormhole and a black hole?

What is antimatter, and why does the Enterprise need it?

Are time loops really possible, and can I kill my grandmother before I am born?

Discover the answers to these and many other fascinating questions from a renowned physicist and dedicated Trekker.

Featuring a section on the top ten physics bloopers and blunders in Star Trek as selected by Nobel-Prize winning physicists and other devout Trekkers!

"Today's science fiction is often tomorrow's science fact. The physics that underlines Star Trek is surely worth investigating. To confine our attention to terrestrial matters would be to limit the human spirit."

--From the foreword by Stephen Hawking

NATIONAL BESTSELLER!

This book was not prepared, approved, licensed, or endorsed by any entity involved in creating or producing the Star Trek television series or films.

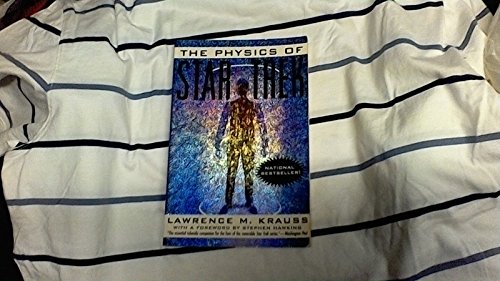

The Physics of Star Trek

By Lawrence M. KraussPerennial

Copyright © 1996 Lawrence M. Krauss

All right reserved.ISBN: 9780060977108

CHAPTER ONE

NEWTON

Antes

"No matter where you go, there you are."

--From a plaque on the starship Excelsior, in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, presumably borrowed from The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai

You are at the helm of the starship Defiant (NCC-1764), currentlyin orbit around the planet Iconia, near the Neutral Zone. Yourmission: to rendezvous with a nearby supply vessel at the other end ofthis solar system in order to pick up components to repair faultytransporter primary energizing coils, There is no need to achieve warpspeeds; you direct the impulse drive to be set at full power for leisurelyhalf-light-speed travel, which should bring you to your destination ina few hours, giving you time to bring the captain's log up to date.However, as you begin to pull out of orbit, you feel an intense pressurein your chest. Your hands are leaden, and you are glued to yourseat. Your mouth is fixed in an evil-looking grimace, your eyes feellike they are about to burst out of their sockers, and the blood flowingthrough your body refuses to rise to your head. Slowly, you loseconsciousness . . . and within minutes you die.

What happened? It is not the first signs of spatial "interphase"drift, which will later overwhelm the ship, or an attack from a previouslycloaked Romulan vessel. Rather, you have fallen prey to somethingfar more powerful. The ingenious writers of Star Trek, on whomyou depend, have not yet invented inertial dampers, which they willintroduce sometime later in the series. You have been defeated bynothing more exotic than Isaac Newton's laws of motion--the veryfirst things one can forget about high school physics.

OK, I know some trekkers out there are saying to themselves,"How lame! Don't give me Newton. Tell me things I really want toknow, like `How does warp drive work?' or `What is the flash beforegoing to warp speed--is it like a sonic boom?' or `What is a dilithiumcrystal anyway?'" All I can say is that we will get there eventually.Travel in the Star Trek universe involves some of the most exotic conceptsin physics, But many different aspects come together before wecan really address everyone's most fundamental question about StarTrek; "Is any of this really possible, and if so, how?"

To go where no one has gone before--indeed, before we even getout of Starfleet Headquarters--we first have to confront the samepeculiarities that Galileo and Newton did over three hundred yearsago. The ultimate motivation will be the truly cosmic question whichwas at the heart of Gene Roddenberry's vision of Star Trek and which,to me, makes this whole subject worth thinking about: "What doesmodern science allow us to imagine about our possible future as acivilization?"

Anyone who has ever been in an airplane or a fast car knows thefeeling of being pushed back into the scat as the vehicle acceleratesfrom a standstill. This phenomenon works with a vengeance aboarda starship. The fusion reactions in the impulse drive produce hugepressures, which push gases and radiation backward away from theship at high velocity. It is the backreaction force on the engines--fromthe escaping gas and radiation--that causes the engines to "recoil"forward. The ship, being anchored to the engines, also recoils forward.At the helm, you are pushed forward too, by the force of thecaptain's seat on your body. In turn, your body pushes back on theseat.

Now, here's the catch. Just as a hammer driven at high velocitytoward your head will produce a force on your skull which can easilybe lethal, the captain's seat will kill you if the force it applies to youis too great. Jet pilots and NASA have a name for the force exerted onyour body while you undergo high accelerations (as in a plane or duringa space launch): G-forces. I can describe these by recourse to myaching back: As I am sitting at my computer terminal busily typing, Ifeel the ever-present pressure of my office chair on my buttocks--apressure that I have learned to live with (yet, I might add, that my buttocksare slowly reacting to in a very noncosmetic way). The force onmy buttocks results from the pull of gravity, which if given free reinwould accelerate me downward into the Earth. What stops me fromaccelerating--indeed, from moving beyond my seat--is the groundexerting an opposite upward force on my house's concrete and steelframe, which exerts an upward force on the wood floor of my second-floorstudy, which exerts a force on my chair, which in turn exerts aforce on the part of my body in contact with it. If the Earth were twiceas massive but had the same diameter, the pressure on my buttockswould be twice as great. The upward forces would have to compensatefor the force of gravity by being twice as strong.

The same factors must be taken into account in space travel. If youare in the captain's seat and you issue a command for the ship toaccelerate, you must take into account the force with which the seatwill push you forward. if you request an acceleration twice as great,the force on you from the seat will be twice as great. The greater theacceleration, the greater the push. The only problem is that nothingcan withstand the kind of force needed to accelerate to impulse speedquickly--certainly not your body.

By the way, this same problem crops up in different contextsthroughout Star Trek--even on Earth. At the beginning of Star TrekV: The Final Frontier, James Kirk is free-climbing while on vacation inYosemite when he slips and falls. Spock, who has on his rocket boots,speeds to the rescue, aborting the captain's fall within a foot or twoof the ground. Unfortunately, this is a case where the solution can beas bad as the problem. It is the process of stopping over a distance ofa few inches which can kill you, whether or not it is the ground thatdoes the stopping or Spock's Vulcan grip.

Well before the reaction forces that will physically tear or breakyour body occur, other severe physiological problems set in. First andforemost, it becomes impossible for your heart to pump stronglyenough to force the blood up to your head. This is why fighter pilotssometimes black out when they perform maneuvers involving rapidacceleration. Special suits have been created to force the blood upfrom pilots' legs to keep them conscious during acceleration. Thisphysiological reaction remains one of the limiting factors in determininghow fist the acceleration of present-day spacecraft can be, andit is why NASA, unlike Jules Verne in his classic From the Earth to theMoon, has never launched three men into orbit from a giant cannon.

If I want to accelerate from rest to, say, 150,000 km/sec, or abouthalf the speed of light, I have to do it gradually, so that my body willnot be torn apart in the process. In order not to be pushed back intomy seat with a force greater than 3G, my acceleration must be nomore than three times the downward acceleration of falling objects onEarth. At this rate of acceleration, it would take some 5 million seconds,or about 2 1/2 months, to reach half light speed! This would notmake for an exciting episode.

To resolve this dilemma, sometime after the production of the firstConstitution Class starship--the Enterprise (NCC-1701)--the StarTrek writers had to develop a response to the criticism that the accelerationsaboard a starship would instantly turn the crew into...