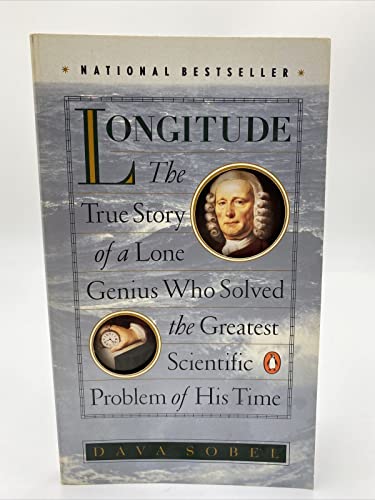

An award-winning science journalist traces the development of the marine chronometer by an obscure, uneducated clock maker--an invention that revolutionized sailing by allowing navigators to determine their ship's longitude. Reprint. Tour.

Longitude

The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His TimeBy Dava SobelPenguin Books

Copyright © 1996 Dava Sobel

All right reserved.ISBN: 0140258795

CHAPTER ONE

Imaginary Lines

When I'm playful I use the meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude for a seine, and drag the Atlantic Ocean for whales. --MARK TWAIN, Life on the Mississippi

: : Once on a Wednesday excursion when Iwas a little girl, my father bought me abeaded wire ball that I loved. At atouch, I could collapse the toy into a flatcoil between my palms, or pop it open to make a hollowsphere. Rounded out, it resembled a tiny Earth,because its hinged wires traced the same pattern ofintersecting circles that I had seen on the globe in myschoolroom--the thin black lines of latitude and longitude.The few colored beads slid along the wirepaths haphazardly, like ships on the high seas.

My father strode up Fifth Avenue to RockefellerCenter with me on his shoulders, and we stopped tostare at the statue of Atlas, carrying Heaven and Earthon his.

The bronze orb that Atlas held aloft, like the wiretoy in my hands, was a see-through world, defined byimaginary lines. The Equator. The Ecliptic. The Tropicof Cancer. The Tropic of Capricorn. The Arctic Circle.The prime meridian. Even then I could recognize,in the graph-paper grid imposed on the globe, a powerfulsymbol of all the real lands and waters on theplanet.

Today, the latitude and longitude lines governwith more authority than I could have imagined forty-oddyears ago, for they stay fixed as the world changesits configuration underneath them--with continentsadrift across a widening sea, and national boundariesrepeatedly redrawn by war or peace.

As a child, I learned the trick for remembering thedifference between latitude and longitude. The latitudelines, the parallels, really do stay parallel to eachother as they girdle the globe from the Equator to thepoles in a series of shrinking concentric rings. The meridiansof longitude go the other way: They loop fromthe North Pole to the South and back again in greatcircles of the same size, so they all converge at theends of the Earth.

Lines of latitude and longitude began crisscrossingour worldview in ancient times, at least three centuriesbefore the birth of Christ. By A.D. 150, the cartographerand astronomer Ptolemy had plotted them onthe twenty-seven maps of his first world atlas. Alsofor this landmark volume, Ptolemy listed all the placenames in an index, in alphabetical order, with the latitudeand longitude of each--as well as he could gaugethem from travelers' reports. Ptolemy himself hadonly an armchair appreciation of the wider world. Acommon misconception of his day held that anyoneliving below the Equator would melt into deformityfrom the horrible heat.

The Equator marked the zero-degree parallel oflatitude for Ptolemy. He did not choose it arbitrarilybut took it on higher authority from his predecessors,who had derived it from nature while observing themotions of the heavenly bodies. The sun, moon, andplanets pass almost directly overhead at the Equator.Likewise the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn,two other famous parallels' assume their positionsat the sun's command. They mark the northernand southern boundaries of the sun's apparent motionover the course of the year.

Ptolemy was free, however, to lay his prime meridian,the zero-degree longitude line, wherever heliked. He chose to run it through the Fortunate Islands(now called the Canary & Madeira Islands) off thenorthwest coast of Africa. Later mapmakers movedthe prime meridian to the Azores and to the CapeVerde Islands, as well as to Rome, Copenhagen, Jerusalem,St. Petersburg, Pisa, Paris, and Philadelphia,among other places, before it settled down at last inLondon. As the world turns, any line drawn from poleto pole may serve as well as any other for a startingline of reference. The placement of the prime meridianis a purely political decision.

Here lies the real, hard-core difference betweenlatitude and longitude--beyond the superficial differencein line direction that any child can see: The zero-degreeparallel of latitude is fixed by the laws of nature,while the zero-degree meridian of longitudeshifts like the sands of time. This difference makesfinding latitude child's play, and turns the determinationof longitude, especially at sea, into an adult dilemma-onethat stumped the wisest minds of theworld for the better part of human history.

Any sailor worth his salt can gauge his latitude wellenough by the length of the day, or by the height ofthe sun or known guide stars above the horizon. ChristopherColumbus followed a straight path across theAtlantic when he "sailed the parallel" on his 1492journey, and the technique would doubtless have carriedhim to the Indies had not the Americas intervened.

The measurement of longitude meridians, in comparison,is tempered by time. To learn one's longitudeat sea, one needs to know what time it is aboard shipand also the time at the home port or another placeof known longitude--at that very same moment. Thetwo clock times enable the navigator to convert thehour difference into a geographical separation. Sincethe Earth takes twenty-four hours to complete onefull revolution of three hundred sixty degrees, onehour marks one twenty-fourth of a spin, or fifteen degrees.And so each hour's time difference between theship and the starting point marks a progress of fifteendegrees of longitude to the east or west. Every day atsea, when the navigator resets his ship's clock to localnoon when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky,and then consults the home-port clock, every hour'sdiscrepancy between them translates into another fifteendegrees of longitude.

Those same fifteen degrees of longitude also correspondto a distance traveled. At the Equator, wherethe girth of the Earth is greatest, fifteen degreesstretch fully one thousand miles. North or south ofthat line, however, the mileage value of each degreedecreases. One degree of longitude equals four minutesof time the world over, but in terms of distance,one degree shrinks from sixty-eight miles at the Equatorto virtually nothing at the poles.

Precise knowledge of the hour in two differentplaces at once--a longitude prerequisite so easily accessibletoday from any pair of cheap wristwatches--wasutterly unattainable up to and including the eraof pendulum clocks. On the deck of a rolling ship,such clocks would slow down, or speed up, or stoprunning altogether. Normal changes in temperatureencountered en route from a cold country of origin toa tropical trade zone thinned or thickened a clock'slubricating oil and made its metal parts expand or contractwith equally disastrous results. A rise or fall inbarometric pressure, or the subtle variations in theEarth's gravity from one latitude to another, couldalso cause a clock to gain or lose time.

For lack of a practical method of determining longitude,every great captain in the Age of Explorationbecame lost at sea despite the best available chartsand compasses. From Vasco da Gama to Vasco Nunezde Balboa, from Ferdinand Magellan to Sir FrancisDrake--they all got where they were going willy-nilly,by forces attributed to good luck or the grace of God.

As more and more sailing vessels set out to conqueror explore new territories, to wage war, or toferry gold and commodities between foreign lands,the wealth of nations floated upon the oceans. Andstill no ship owned a...