Verwandte Artikel zu Sisters of The Revolution: A Femimist Speculative Fiction...

Inhaltsangabe

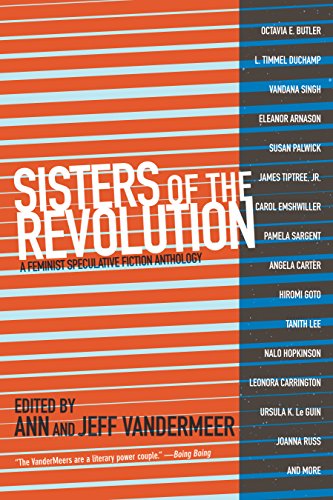

Sisters of the Revolution gathers a highly curated selection of feminist speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, horror and more) chosen by one of the most respected editorial teams in speculative literature today, the award-winning Ann and Jeff VanderMeer. Including stories from the 1970s to the present day, the collection seeks to expand the conversation about feminism while engaging the reader in a wealth of imaginative ideas. Sisters of the Revolution seeks to expand the ideas of both contemporary fiction and feminism to new fronts.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Ann VanderMeer is the Hugo Award&;winning editor of Weird Tales and the founder of Buzzcity Press. She currently serves as an acquiring fiction editor for Tor.com, Cheeky Frawg Books, and Weirdfictionreview.com. She has also won a World Fantasy Award and a British Fantasy Award for coediting The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories. She is the coeditor of numerous titles, including The Kosher Guide to Imaginary Animals, Steampunk, Steampunk II: Steampunk Reloaded, and The Steampunk Bible. Jeff VanderMeer is a columnist, a publisher, and the author of several books, including Booklife, City of Saints & Madmen, Finch, Shriek: An Afterword, Veniss Underground, and Wonderbook, the world&;s first fully illustrated, full-color creative writing guide. He is the cofounder of Weirdfictionreview.com and Cheeky Frawg Books and has edited or coedited 12 fiction anthologies. His nonfiction appears in the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, and the Los Angeles Times, among others. He is a three-time World Fantasy Award winner. They live in Tallahassee, Florida.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Sisters of the Revolution

A Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology

By Ann VanderMeer Jeff VanderMeerPM Press

All rights reserved.

Contents

Introduction,

The Forbidden Words of Margaret A. L. Timmel Duchamp,

My Flannel Knickers Leonora Carrington,

The Mothers of Shark Island Kit Reed,

The Palm Tree Bandit Nnedi Okorafor,

The Grammarian's Five Daughters Eleanor Arnason,

And Salome Danced Kelley Eskridge,

The Perfect Married Woman Angélica Gorodischer,

The Glass Bottle Trick Nalo Hopkinson,

Their Mother's Tears: The Fourth Letter Leena Krohn,

The Screwfly Solution James Tiptree, Jr.,

Seven Losses of na Re Rose Lemberg,

The Evening and the Morning and the Night Octavia E. Butler,

The Sleep of Plants Anne Richter,

The Men Who Live in Trees Kelly Barnhill,

Tales from the Breast Hiromi Goto,

The Fall River Axe Murders Angela Carter,

Love and Sex Among the Invertebrates Pat Murphy,

When It Changed Joanna Russ,

The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet Vandana Singh,

Gestella Susan Palwick,

Boys Carol Emshwiller,

Stable Strategies for Middle Management Eileen Gunn,

Northern Chess Tanith Lee,

Aunts Karin Tidbeck,

Sur Ursula K. Le Guin,

Fears Pamela Sargent,

Detours on the Way to Nothing Rachel Swirsky,

Thirteen Ways of Looking at Space/Time Catherynne M. Valente,

Home by the Sea Élisabeth Vonarburg,

CHAPTER 1

L. TIMMEL DUCHAMP

The Forbidden Words of Margaret A.

L. Timmel Duchamp is an American writer, editor, and publisher. Her short fiction has been published in Asimov's Science Fiction, Pulphouse, and a variety of anthologies such as Full Spectrum. In addition to her own writing of both fiction and essays, she runs Aqueduct Press, providing a platform for the voices of others. "The Forbidden Words of Margaret A." tells the story of a woman imprisoned for speaking out. Her words are considered so dangerous that the government adopted a constitutional amendment limiting free speech, specifically the words of Margaret A. The story was first published in Pulphouse: The Hardback Magazine in 1980.

[N.B.: The following report was prepared exclusively for the use of the National Journalists' Association for the Recovery of Freedom of the Press by a journalist who visited Margaret A. sometime within the last two years. JATROF requests that this report not be duplicated in any form or removed from JATROF offices and that the information provided herein be used with care and discretion.]

Introduction

Despite the once-monthly photo-ops the Bureau of Prisons allows, firsthand uncensored accounts of contact with Margaret A. are rare. The following, though it falls short of providing a verbatim transcript of Margaret A.'s words, attempts to offer a fuller, more faithful rendition of one journalist's contact with Margaret A. than has ever been publicly available. This reporter's awareness of the importance to her colleagues of such an account, as well as of the danger disseminating it to a broader audience would entail for all involved in such an effort, has prompted the deposit of this document with JATROF.

Before describing my contact with Margaret A., I wish to emphasize the constraints that circumscribed my meeting with Margaret A. Members of JATROF will necessarily be familiar with the techniques the government uses to manipulate public perception of data. Certainly I, going into the photo-op, considered myself well up on the government's tricks for controlling the contextualization of issues it cares about. Yet I personally can vouch for the insidious danger of momentarily forgetting the obvious: where Margaret A. is concerned, much slips our attention, keeping us from thinking clearly and objectively about the concrete facts before our eyes. I'm not sure how this happens, only that it does. The information we have about Margaret A. somehow does not get added up correctly. I urge readers, then, not to skip over details already known to you, but to take my iteration of them as a caveat, as a reminder, as an aid to thought about an issue that for all its publicity remains remarkably murky. I thus ask my readers' indulgence for excursions into what may seem unnecessary political analysis and speculation. I know of no other way to wrest the framing of my own contact with Margaret A. out of the murk and mire that tends to obscure any objective recounting of facts relating to the Margaret A. situation.

To start with the most obvious: Margaret A. permits only one photo-op a month. The Bureau of Prisons (naturally pleased to make known to the public that the government can't be held responsible for thwarting the public's desire for "news" of her) doesn't allow Margaret A. to choose from among those who apply, and in this way effectively controls media access to her. The Justice Department of course would prefer to dispense with these sessions altogether, but when at the beginning of Margaret A.'s imprisonment they denied all media access to her, their attempt to sink Margaret A.'s existence into oblivion instead provoked a constant stream of speculation and protest that threatened them with not only the repeal of the Margaret A. Amendment, but even worse a resurgence of the massive civil disorder that had prompted her incarceration and silencing in the first place. Beyond obliterating Margaret A.'s words, I would argue that the government places the next highest priority on preventing the public from perceiving Margaret A. as a martyr. That consideration alone can explain why the conditions of her special detention in a quonset hut within the confines of the Vandenberg Air Force Base is such that no person or organization — not even the ACLU or Amnesty International, organizations which deplore the fact of her confinement — can reasonably fault them. The responsible journalist undertaking coverage of Margaret A. must bear these points in mind.

Selection for and Constraints upon the Photo-op

I've been fascinated by Margaret A. my entire adult life. I entered journalism precisely so that I'd have a shot at firsthand contact with Margaret A. and have systematically pursued that goal with every career step I've taken. (I realize that to most members of JATROF it is the implications of the Margaret A. Amendment and not Margaret A. herself that matter most. The words of Margaret A., however, for a brief time radically changed the way I looked at the world. Since losing it, I've never ceased to yearn for another glimpse of that perspective. Surely of all people, JATROF members can most appreciate that such a goal does not belie the ideals of the profession?) Accordingly, I studied the Bureau of Prison's selection preferences, worked my way into suitable employment, then patiently and quietly waited. I lived carefully. I kept myself as clean of suspect contacts as any working journalist can. When finally I was selected for one of Margaret A.'s photo-ops, Circumspection has been rewarded, I congratulated myself. Reading and rereading the official notification I felt as though I had just been granted a visa to the promised land.

An invitation to meet Simon Bartkey had been attached to the visa, however. Naturally this disconcerted me: an in-person screening by a Justice Department official is quite a bit different from scrutiny of one's record. But I told myself that I'd been "good" for so long that my professionalism would see me over this last hurdle. Thus one month before I was due to meet Margaret A., my producer and I flew to Washington and met this Justice Department official assigned to what they call "the Margaret A. Desk" — an "expert" who cheerfully admitted to me that he had never heard or read any of Margaret A.'s words himself. I couldn't help but be impressed with the show they run, for the BOP has it down to a fine procedure designed to ensure that everything flows with the smoothness and predictability of a high-precision robotics assembly. Besides providing an opportunity for one last intense scrutiny of the journalists they've selected, to their way of thinking, a visit to Simon Bartkey sets both the context journalists are supposed to use as well as the ground rules.

Let me note in reminder here that Simon Bartkey has survived three different administrations precisely because he's accounted an "expert" on "the Margaret A. situation." Since the early days of the Margaret A. phenomenon, each administration has fretted about the public's continuing fascination with her. Bartkey expressed it to me in these words: "This ongoing interest in her defies all logic. Her words — except for a few hoarded tapes, newspapers, and samizdat — have been completely obliterated, and the general public has no access to them, and certainly no memory of them. The American public has never been known to have such a long attention span, especially with regard to someone not continually providing ever new and more exciting grist to the media's mill. Why then do people still want to see her? Why haven't they forgotten about her?" (How it must gall politicians that Margaret A. has for the last fifteen years enjoyed higher name recognition than each sitting U.S. president during the same period.)

Though it was the most important event in my life (I was nineteen when it happened), I can't remember any of her words. I was too young and naive at the time to hold onto newspapers and the ad hoc ephemera figures like Margaret A. invariably generate, and certainly never dreamed that her words could be expunged from the internet. And like most people I never dreamed a person's words could become illegal. One hears rumors, of course, of old tapes and newspapers carefully hoarded — yet though I've faithfully tracked every such rumor I've caught wind of, none has ever panned out.

For perhaps twenty of the fifty-five minutes I spent being briefed by him, Bartkey took great pleasure in explaining to me how the passage of time will ultimately eclipse Margaret A.'s public visibility. Leaning back in his padded red leather chair, he announced that the generational gap more than anything will finally isolate those who persist in "worshiping at the altar of her memory." His fingers stroking his mandala-embossed bottle green silk tie, he insisted that Margaret A. can mean nothing to college kids since they were only infants at the time of the Margaret A. phenomenon. He might conceivably prove to be correct, but I don't think so. The kids I've talked to find the Margaret A. Amendment so irrational and egregious an offense against the spirit of the First Amendment that they're suspicious of everything they've been told about it. If no records of Margaret A.'s words still exist, neither do reports of the massive civil disorder their civics textbooks use to justify the passage of the amendment. The fact of the Margaret A. Amendment, I think, has got to fill them with suspicions of a cover-up. Consider: the only images they connect with Margaret A. now are the videos and photos taken of this U.S. citizen living in internal exile, a small middle-aged woman dwarfed by the deadly array of missiles and radar installations and armed guards surrounding her. I doubt that young people are capable of understanding that anyone's particular use of language in and of itself could have threatened the dissolution of every form of government in this country (much less provoked the unprecedented, draconian measure of a constitutional amendment to silence it). I've seen the cynical skepticism in their faces when older people talk about those days. How could any arrangement of words on paper, any speech recorded on tape be as dangerous as government authorities say? And why ban no one else's speech, not even that of her most persistent followers (except of course when quoting her)? Young people don't believe it was that simple. When I listen to their questions I've no trouble deducing that they believe the government is covering up the past existence of a powerful, armed, revolutionary force. They consider the amendment not only a cover-up but also a gratuitous measure designed to curtail speech and establish a precedent for future curtailments.

Needless to say I didn't share such observations with Bartkey any more than I offered him my theory that the new generation is not only suspicious of a cover-up but also dying for a taste of forbidden fruit. While doubting its vaunted potency (or toxicity, depending on one's point of view), they long to know what it is they're being denied. This sounds paradoxical, I admit, yet I've heard a note of resentment in their expressions of skepticism. The dangers of Margaret A.'s words may not be apparent to them, but by labeling the fruit forbidden — fruit their elders had been privileged enough to taste — the amendment — which they consider a cover-up to start with — is provoking resentment in this new generation coming of age. Rather than developing amnesia about Margaret A., the new generation may well become obsessed with her. I wouldn't be at all surprised if new, bizarrely conceived cults didn't spring up around the Margaret A. phenomenon.

I don't mean to imply that I'd approve of bizarre cults and obsession with forbidden fruit. The fascination I and others like me feel for Margaret A. is probably as incomprehensible to the young people as the government's fear of her words. (Our diverse reactions to Margaret A. seem to mark a Great Divide for most people in this country.) But something about the very idea of her — regardless of whether her ideas are ever remembered — the very idea of this woman shut up in the middle of a high-security military base because her words are so potent ... well, that idea does something to almost everyone in this country, including those who find the Margaret A. phenomenon frightening (excepting, of course, the anti-free speech activists). If I were Bartkey I'd be worried: it's only a matter of time before the Margaret A. Amendment is repealed. And if Margaret A. is still alive then, things could explode.

Margaret A.'s "Security"

All we ever saw of Vandenberg proper was its perimeter fence and gate. Even before we'd handed our documents to the guard three people wearing nonmilitary uniforms converged on us and ordered us out onto the tarmac. One of them then climbed into the van and turned it around and drove it somewhere away from the base; the other two ordered us into a tiny quonset hut off to the right. This confused me, and I wondered whether there had been a foul-up of some sort, or whether the background checks had turned up something about one of us the Justice Department didn't like. (I even wondered — fleetingly — whether for some convoluted tangle of reasoning they kept her there in that quonset hut, outside the base's perimeter fence).

What followed in the hut rendered my speculations absurd. Bartkey had of course made us sign an agreement that we be subject to strip searches, that we use their equipment, that all materials be edited by them, and that we submit to an extensive debriefing afterwards. I bore with the strip and body cavity search without protest, of course, since journalists are commonly obliged to endure such ordeals when entering prisons to interview inmates. (I'm sure colleagues reading this know well how one attempts in such circumstances to put the best face on an awkward, uncomfortable situation.) Nor did I protest the condition that the Bureau of Prisons be granted total editorial power, for obviously the Margaret A. Amendment might otherwise be flouted. But their insistence that we use their equipment — that bothered me for some elusive, hard-to-define reason. Bartkey had explained that their equipment ran without an audio track, and since no one by the terms of the Margaret A. Amendment could legally tape her speech, my conscious reaction focused on that obvious point. But as I was putting my thoroughly searched clothing back on I learned that I could not take my shoulder bag in with me and realized that not only would there be no audio tape, there would also be no pen and paper, no laptop computer, no note-taking beyond what I could force into my own, ill-trained mental memory. Naturally I protested. (I am, after all, the woman who relies on her computer to tell her such things as when to have her hair cut, what time to eat lunch, and how long it has been since she's written to her mother.) It made no difference, of course. I was told that if I didn't choose to abide by the rules they'd take the producer and crew in without me.

After hitting us with another review of all the ground rules, they herded us into the windowless back of a Bureau of Prisons van and drove us an undisclosed turn-filled and occasionally bumpy distance. The van stopped for at least a minute three separate times before pausing briefly — as at a stop sign, or to allow the opening of a gate (I deduce the latter to have been the case) — and then moved for only two or three seconds before coming to a final halt. When the engine cut it only then came to me in a breathless rush that what I had been waiting for nearly half my life was actually about to happen. Margaret A.'s words are forbidden. Yet for a few minutes I would have the privilege of hearing her speak. Only "trivialities," granted, they would allow nothing else — guards with radio receivers in their ears would be on hand to see to that: but still the words would be Margaret A.'s, and even her "trivial" speech, I felt certain, would be potent, perhaps electrifying. And I believed that on hearing Margaret A. speak I would remember all that I had forgotten about those days and would understand all that had eluded me throughout my adult life.

This pre-contact assumption derived not from romantic dreams cherished from adolescence, but from what I had (discreetly) gleaned about the conditions of Margaret A.'s life of exile. I had learned, for instance, from a highly reliable source formerly employed by the Justice Department, that the Bureau of Prisons had run through more than five hundred guards on the Margaret A. assignment, all of whom had quit the BOP subsequent to their removal from duty at Vandenberg. What continues to strike me as extraordinary about this is that the guards assigned to Margaret A. have always been — and continue to be — taken exclusively from a pool of guards experienced in working in high security federal facilities. Each guard previous to meeting Margaret A. is warned that all speech uttered within the confines of the prisoner's quarters will be recorded and examined. Before starting duty at Vandenberg each newly assigned guard undergoes rigorous orientation sessions and while on duty at Vandenberg reports for debriefing after each personal contact with Margaret A. Yet no guard has ever gone on to a new assignment following contact with Margaret A. Another curious statistic: those assigned to audio surveillance of the words spoken in Margaret A's quarters inevitably "burn out" during their second year of monitoring Margaret A. Consider: Margaret A. is forbidden ever to speak about anything remotely "political." How then can she so consistently corrupt every guard who has had contact with her and disturb every monitor who has been assigned to listen to her (non-political: "trivial") conversation? It never occurred to me to wonder what Bartkey meant when he said that all conversation with Margaret A. must be confined to "trivial, non-political small-talk." He and other officials outlined for me the sorts of questions I must avoid raising — ranging from the subject of her confinement, the Margaret A. Amendment, and the public's continuing interest in her to the specific points upon which, according to rumor (since documents no longer exist, one can refer only to rumors or fuzzy nodes of memory), she had spoken during the brief initial period of the Margaret A. phenomenon. I think I assumed that the corruption of her guards had more to do with Margaret A.'s personality than with the "smalltalk" she exchanged with them (never mind that this did not address the monitors' eventual termination by the Justice Department). Thus as our escort opened the back door of the van I told myself I would now be meeting not only the most remarkable woman in history, but probably the most charismatic, charming, and possibly lovable person I would ever have the pleasure of knowing.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Sisters of the Revolution by Ann VanderMeer Jeff VanderMeer. Copyright © 2015 PM Press. Excerpted by permission of PM Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Gratis für den Versand innerhalb von/der Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenEUR 0,61 für den Versand von USA nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für Sisters of The Revolution: A Femimist Speculative Fiction...

Sisters of The Revolution : A Femimist Speculative Fiction Anthology

Anbieter: medimops, Berlin, Deutschland

Zustand: very good. Gut/Very good: Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit wenigen Gebrauchsspuren an Einband, Schutzumschlag oder Seiten. / Describes a book or dust jacket that does show some signs of wear on either the binding, dust jacket or pages. Artikel-Nr. M01629630357-V

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Sisters of The Revolution : A Femimist Speculative Fiction Anthology: A Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. GOR007202605

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sisters of The Revolution

Anbieter: PBShop.store US, Wood Dale, IL, USA

PAP. Zustand: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Artikel-Nr. EB-9781629630359

Anzahl: 5 verfügbar

SISTERS OF THE REVOLUTION

Anbieter: Speedyhen, London, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: NEW. Artikel-Nr. NW9781629630359

Anzahl: 5 verfügbar

Sisters of the Revolution : A Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology

Anbieter: AHA-BUCH GmbH, Einbeck, Deutschland

Taschenbuch. Zustand: Neu. Neuware - Sisters of the Revolution gathers a highly curated selection of feminist speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, horror, and more) chosen by one of the most respected editorial teams in speculative literature today, the award-winning Ann and Jeff VanderMeer. Including stories from the 1970s to the present day, the collection seeks to expand the conversation about feminism while engaging the reader in a wealth of imaginative ideas. -- taken from back cover. Artikel-Nr. 9781629630359

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Sisters of The Revolution

Anbieter: PBShop.store UK, Fairford, GLOS, Vereinigtes Königreich

PAP. Zustand: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Artikel-Nr. EB-9781629630359

Anzahl: 5 verfügbar

Sisters of the Revolution

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Zustand: New. KlappentextSisters of the Revolution gathers a highly curated selection of feminist speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, horror, and more) chosen by one of the most respected editorial teams in speculative literature today, the. Artikel-Nr. 31221331

Anzahl: 5 verfügbar

Sisters of the Revolution: A Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology

Anbieter: Powell's Bookstores Chicago, ABAA, Chicago, IL, USA

Zustand: Used - Like New. 2015. Paperback. Fine. Artikel-Nr. BR32706

Anzahl: 4 verfügbar

Sisters of the Revolution: A Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology

Anbieter: Ria Christie Collections, Uxbridge, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: New. In. Artikel-Nr. ria9781629630359_new

Anzahl: 5 verfügbar

Sisters Of The Revolution: A Femimist Speculative Fiction Anthology

Anbieter: Kennys Bookstore, Olney, MD, USA

Zustand: New. Editor(s): VanderMeer, Jeff; VanderMeer, Ann. Num Pages: 344 pages. BIC Classification: FL; FYB. Category: (G) General (US: Trade). Dimension: 231 x 153 x 27. Weight in Grams: 384. . 2015. Paperback. . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Artikel-Nr. V9781629630359

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar