Inhaltsangabe

--Publishers Weekly, Starred review

"Richard Wright, Nelson Algren, and Sandra Cisneros are not crime-fiction writers, and yet their Chicago certainly embodies the individual-crushing ethos endemic to noir. Meno also includes stories from writers who could easily have been overlooked (Percy Spurlark Parker, Hugh Holton) to ensure that diverse voices, and neighborhoods, are represented. Add in smart and essential choices from Fredric Brown, Sara Paretsky, and Stuart Kaminsky, and you have not an anthology not for crime-fiction purists, perhaps, but a thought-provoking document all the same."

--Booklist

"The fifteen short stories comprising Chicago Noir: The Classics, which are knowledgeably compiled and deftly edited by Joe Meno, are true gems of the noir literary tradition....Chicago Noir: The Classics is a consistently entertaining and will prove to be an enduringly popular addition to community library Mystery/Suspense collections."

--Midwest Book Review

"I've always enjoyed reading noir. Dark, ironic mysteries are a good read to me. Since this collection includes old classics as well as some new stories, I knew it would be good....I wasn't disappointed."

--Journey of a Bookseller

"Chicago Noir The Classics does everything anthologies and noir are supposed to, but this title achieves an unheralded goal that deserves notice....This is wonderful diversity, coming both unexpected and unhearalded. Anthologies are supposed to convey a sense of having covered the territory, Joe Meno has. Ethnically diverse city, ethnically diverse plots. Better, Chicago Noir The Classics showcases diversity as normal, everyday. This adds inescapable satisfaction to a sense of the editor's having covered the territory."

--La Bloga

"A worthy addition to the Akashic Books noir series."

--Book Chase

Although Los Angeles may be considered the most quintessentially "noir" American city, this volume reveals that pound-for-pound, Chicago has historically been able to stand up to any other metropolis in the noir arena.

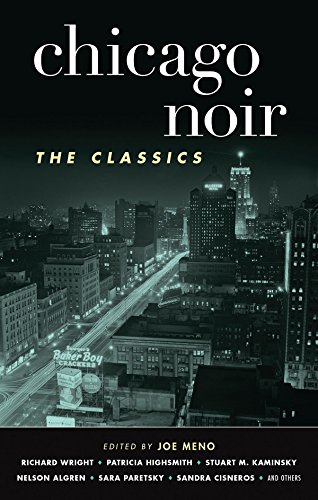

Classic reprints from: Harry Stephen Keeler, Sherwood Anderson, Max Allan Collins, Richard Wright, Nelson Algren, Fredric Brown, Patricia Highsmith, Barry Gifford, Stuart M. Kaminsky, Libby Fischer Hellmann, Sara Paretsky, Percy Spurlark Parker, Sandra Cisneros, Hugh Holton, and Stuart Dybek.

From the introduction by Joe Meno:

"More corrupt than New York, less glamorous than LA, Chicago has more murders per capita than any other city its size. With its sleek skyscrapers bisecting the fading sky like an unspoken threat, Chicago is the closest metropolis to the mythical city of shadows as first described in the work of Chandler, Hammett, and Cain. Only in Chicago do instituted color lines offer generation after generation of poverty and violence, only in Chicago do the majority of governors do prison time, only in Chicago do the dead actually vote twice.

"Chicago--more than the metropolis that gave the world Al Capone, the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre, the death of John Dillinger, the crimes of Leopold and Loeb, the horrors of John Wayne Gacy, the unprecedented institutional corruption of so many recent public officials, more than the birthplace of Raymond Chandler--is a city of darkness. This darkness is not an act of over-imagination. It's the unadulterated truth. It's a pointed though necessary reminder of the grave tragedies of the past and the failed possibilities of the present. Fifty years in the future, I hope these stories are read only as fiction, as somewhat distant fantasy. Here's hoping for some light."

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Chicago Noir

The Classics

By Joe MenoAkashic Books

All rights reserved.

Contents

Introduction, 11,

PART I: THE JAZZ AGE,

Harry Stephen Keeler 30 Seconds of Darkness Rogers Park 1916, 17,

Sherwood Anderson Brothers Douglas 1921, 37,

Max Allan Collins Kaddish for the Kid West Town 1998, 48,

Richard Wright The Man Who Went to Chicago (excerpt) Illinois Medical District 1945, 77,

PART II: NOIR & NEO-NOIR,

Nelson Algren He Swung and He Missed Lakeview 1942, 93,

Fredric Brown I'll Cut Your Throat Again, Kathleen Magnificent Mile 1948, 102,

Patricia Highsmith The Price of Salt (excerpt) Gold Coast 1952, 124,

Barry Gifford The Starving Dogs of Little Croatia Wicker Park 2009, 137,

Stuart M. Kaminsky Blue Note Woodlawn 1997, 142,

Libby Fischer Hellmann The Whole World Is Watching Grant Park 2007, 160,

PART III: MODERN CRIME,

Sara Paretsky Skin Deep Michigan Avenue 1987, 177,

Percy Spurlark Parker Death and the Point Spread Lawndale 1995, 194,

Sandra Cisneros One Holy Night Pilsen 1988, 214,

Hugh Holton The Thirtieth Amendment Bridgeport 1995, 223,

Stuart Dybek We Didn't Oak Street Beach 1993, 236,

About the Contributors, 250,

Permissions, 254,

Acknowledgments, 256,

INTRODUCTION

Language of Shadows

Noir is the language of shadows, of the world in-between. The shape a stranger's mouth makes murmuring in the dark, the color of a knife flashing in a dead-end alley, the sound of an elevator rising to an unlit floor; noir is the language of stark contrasts, life and death, good and evil, day and night.

First defined in the 1940s and '50s by French academics to describe a specific kind of bleak, black-and-white crime film produced by Hollywood in that era, the term gained popular relevancy in the 1970s and since then has also been applied to various works of literature as well: crime novels, detective stories, mysteries, suspense thrillers, each with elements of the gothic or traditional tragedy. Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep, Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest, and James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice all defined the genre with their conflicted heroes and antiheroes, mysterious plots, murky atmospheres, and punchy, stylized writing. These novelists and their counterparts who published short fiction in pulp magazines like Black Mask depicted the moral uncertainty of the modern age — the human struggle to find meaning in a world that by its nature is necessarily obscure.

Noir writing, like the night, is also, by its very definition, somewhat borderless. The history of crime writing in America bears this out. Black Mask, the pulp magazine that first exposed these sorts of stories to the public, was initially created by journalist H.L. Mencken and drama critic George Jean Nathan to help finance their literary journal, the Smart Set. This dynamic tension between the "highbrow" and the "lowbrow" — between the literary elite and the man on the street — is one of noir's most enduring qualities. Recent award-winning books by the likes of Michael Chabon, Denis Johnson, Jonathan Lethem, Roberto Bolaño, and Cormac McCarthy attest to this liminal phenomenon.

Over the years, the literature of noir has proven to be as essential as any other writing genre. Although highly riveting, it's much more than mere entertainment. It's modern mythology at its most powerful. Like its musical equivalent, jazz, I believe it may be one of America's most enduring cultural contributions.

Considering these aspects of the literature of noir, the city of Chicago is arguably its truest embodiment; more corrupt than New York, less glamorous than LA, Chicago has more murders per capita than any other city its size. With its sleek skyscrapers bisecting the fading sky like an unspoken threat, Chicago is the closest metropolis to the mythical city of shadows as first described in the work of Chandler, Hammett, and Cain. Only in Chicago do instituted color lines offer generation after generation of poverty and violence, only in Chicago do the majority of recent governors do prison time, only in Chicago do the dead actually vote twice. With its public record of bribery, cronyism, and fraud, this is a metropolis so deeply divided — by race, ethnicity, and class — that sociologists had to develop a new term to describe this unfortunate bifurcation. As Nelson Algren best put it, Chicago is and has always been a "city on the make."

The stories collected in this volume all explore this city of shadows, of high contrasts, spanning nearly a century, tracing the earliest explorations into the form. Harry Stephen Keeler's "30 Seconds of Darkness," first published in 1916, demonstrates both the influence of Edgar Allan Poe and the high-minded formality of Charles Dickens. In the 1910s and '20s, Sherwood Anderson — a uniquely American writer with his interest in crime, the grotesque, and the underrepresented — influenced the still-developing genre with Winesburg, Ohio and his popular literary stories including "Brothers." Andersons' work alone would go on to inspire William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, and Nelson Algren, whose story "He Swung and He Missed" echoes much of Anderson's character-driven fiction. Midcentury writing like Richard Wright's "The Man Who Went to Chicago" and Patricia Highsmith's The Price of Salt depict the outsider's view of an ambiguous, foreign place where anonymity reigns and racial and sexual mores are less constrained. Several modern pieces, like Stuart Dybek's "We Didn't," with its poetic repetition and lyrical imagery, and Hugh Holton's "The Thirtieth Amendment," with its dystopian elements, help to expand and redefine the form in new and surprising ways.

Chicago's history of crime writing is extensive, perhaps deserving an encyclopedia all its own. Many fine writers were not included in this collection, though their work has been no less influential: pulp writers like Edgar Rice Burroughs, with his dedication to horror and science fiction, mingling crime with decidedly otherworldly elements; newspaper reporters and fiction writers like Ben Hecht and Ring Lardner, who explored noir in their daily columns and stories (though both of them, well aware of the preferences of the New York publishing apparatus, chose to set most of their noirs in New York City); memorable literary novelists like James T. Farrell and Leon Forrest, who both depicted the grim lives of citizens on the city's South Side. Other important crime writers like Eugene Izzi, with his brand of raw, late-'80s noir, seemed less interested in the short story form, preferring instead to produce unflinching novel after unflinching novel.

Chicago — more than the metropolis that gave the world Al Capone, the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre, the death of John Dillinger, the crimes of Leopold and Loeb, the horrors of John Wayne Gacy, the unprecedented institutional corruption of so many recent public officials, more than the birthplace of Raymond Chandler — is a city of darkness. This darkness is not an act of overimagination. It's the unadulterated truth. It's a pointed though necessary reminder of the grave tragedies of the past and the failed possibilities of the present. Fifty years in the future, I hope these stories are read only as fiction, as somewhat distant fantasy. Here's hoping for some light.

Joe Meno

Chicago, IL

June 2015

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Chicago Noir by Joe Meno. Copyright © 2015 Akashic Books. Excerpted by permission of Akashic Books.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Chicago Noir: The Classics (Akashic Noir Series)

Chicago Noir: the Classics

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 6250192-6

Chicago Noir: The Classics

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G1617752940I3N10