Verwandte Artikel zu The Attacking Ocean: The Past, Present, and Future...

Inhaltsangabe

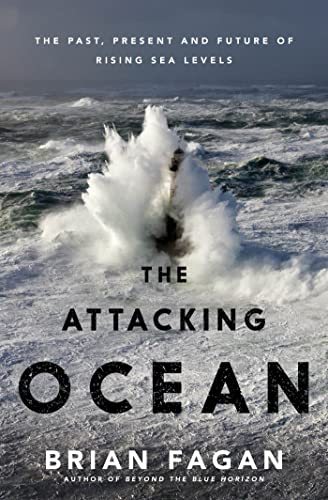

The past fifteen thousand years--the entire span of human civilization--have witnessed dramatic sea level changes, which began with rapid global warming at the end of the Ice Age, when sea levels were more than 700 feet below modern levels. Over the next eleven millennia, the oceans climbed in fits and starts. These rapid changes had little effect on those humans who experienced them, partly because there were so few people on earth, and also because they were able to adjust readily to new coastlines.

Global sea levels stabilized about six thousand years ago except for local adjustments that caused often quite significant changes to places like the Nile Delta. So the curve of inexorably rising seas flattened out as urban civilizations developed in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and South Asia. The earth's population boomed, quintupling from the time of Christ to the Industrial Revolution. The threat from the oceans increased with our crowding along shores to live, fish, and trade.

Since 1860, the world has warmed significantly and the ocean's climb has speeded. The sea level changes are cumulative and gradual; no one knows when they will end. The Attacking Ocean, from celebrated author Brian Fagan, tells a tale of the rising complexity of the relationship between humans and the sea at their doorsteps, a complexity created not by the oceans, which have changed but little. What has changed is us, and the number of us on earth.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Brian Fagan is emeritus professor of anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the author of Beyond the Blue Horizon, Elixir, the Los Angeles Times bestseller Cro-Magnon, and the New York Times bestseller The Great Warming, and many other books, including Fish on Friday, The Long Summer, and The Little Ice Age. He has decades of experience at sea and is the author of several titles for sailors, including the widely praised Cruising Guide to Central and Southern California. He lives in Santa Barbara, CA.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Attacking Ocean

The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

By Brian FaganBLOOMSBURY PRESS

All rights reserved.

Contents

| Preface.................................................................... | xiii |

| Author's Note.............................................................. | xxi |

| 1. Minus One Hundred Twenty-Two Meters and Climbing........................ | 1 |

| MILLENNIA OF DRAMATIC CHANGE............................................... | |

| 2. Doggerland.............................................................. | 23 |

| 3. Euxine and Ta-Mehu...................................................... | 38 |

| 4. "Marduk Laid a Reed on the Face of the Waters".......................... | 53 |

| CATASTROPHIC FORCES........................................................ | |

| 5. "Men Were Swept Away by Waves".......................................... | 71 |

| 6. "The Whole Shoreline Filled"............................................ | 87 |

| 7. "The Abyss of the Depths Was Uncovered"................................. | 100 |

| 8. "The Whole Is Now One Festering Mess"................................... | 113 |

| 9. The Golden Waterway..................................................... | 127 |

| 10. "Wave in the Harbor"................................................... | 144 |

| CHALLENGING INUNDATIONS.................................................... | |

| 11. A Right to Subsistence................................................. | 163 |

| 12. The Dilemma of Islands................................................. | 175 |

| 13. "The Crookedest River in the World".................................... | 192 |

| 14. "Here the Tide Is Ruled, by the Wind, the Moon and Us"................. | 209 |

| Epilogue................................................................... | 225 |

| Acknowledgments............................................................ | 239 |

| Notes...................................................................... | 241 |

| Index...................................................................... | 257 |

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

Minus One HundredTwenty-Two Metersand Climbing

On October 28, 2012, Hurricane Sandy, the largest Atlantic hurricaneon record, came ashore in New Jersey. Sandy's assault and sea surgebrought the ocean into neighborhoods and houses, inundated parkinglots and tunnels, turned parks into lakes. When it was all over and thewater receded, a huge swath of the Northeast American coast lookedlike a battered moonscape. Only Hurricane Katrina, which devastatedNew Orleans in 2005, was more costly. Katrina, with its gigantic seasurge, had been a wake-up call for people living on low-lying coasts, butthe disaster soon receded from the public consciousness. Sandy struck inthe heart of the densely populated Northeastern Corridor of the UnitedStates seven years later and impacted the lives of millions of people.The storm was an epochal demonstration of the power of an attackingocean to destroy and kill in a world where tens of millions of people liveon coastlines close to sea level. This time, people really sat up and tooknotice in the face of an extreme weather event of a type likely to be morecommonplace in a warmer future. As this book goes to press, a seriousdebate about rising sea levels and the hazards they pose for humanitymay have finally begun—but perhaps not.

Sandy developed out of a tropical depression south of Kingston, Jamaica,on October 22. Two days later, it passed over Jamaica, then overCuba and Haiti, killing seventy-one people, before traversing the Bahamas.Come October 28, Sandy strengthened again, eventually makinglandfall about 8 kilometers southwest of Atlantic City, New Jersey,with winds of 150 kilometers an hour. By then, Sandy was not only anunusually large hurricane but also a hybrid storm. A strong Arctic airpattern to the north forced Sandy to take a sharp left into the heavypopulated Northeast when normally it would have veered into the openAtlantic and dissipated there. The blend produced a super storm with awind diameter of 1,850 kilometers, said to be the largest since 1888,when far fewer people lived along the coast and in New York. Unfortunately,the tempest also arrived at a full moon with its astronomical hightides. Sandy was only a Category 1 hurricane, but it triggered a majornatural disaster partly because it descended on a densely populatedseaboard where thousands of houses and other property lie within afew meters of sea level. Imagine the destruction a Category 5 stormwould have wrought—something that could happen in the future.

The scale of destruction was mind-boggling. Sandy brought torrentialdownpours, heavy snowfall, and exceptionally high winds to anarea of the eastern United States larger than Europe. Over one hundredpeople died in the affected states, forty of them in New York City. Thestorm cut off electricity for days for over 4.8 million customers in 15states and the District of Columbia, 1,514,147 of them in New Yorkalone. Most destructive of all, a powerful, record-breaking 4.26-metersea surge swept into New York Harbor on the evening of October 29.The rising waters inundated streets, tunnels, and subways in Lower Manhattan,Staten Island, and elsewhere. Fires caused by electrical explosionsand downed power wires destroyed homes and businesses, over onehundred residences in the Breezy Point area of Queens alone. Even theGround Zero construction site was flooded. Fortunately, the authoritieshad advance warning. In advance of the storm, all public transit systemswere shut down, ferry ser vices were suspended, and airports closed untilit was safe to fly. All major bridges and tunnels into the city were closed.The New York Stock Exchange shut down for two days. Initial recoverywas slow, with shortages of gasoline causing long lines. Rapid transitsystems slowly restored ser vice, but the damage caused by the stormsurge in lower Manhattan delayed reopening of critical links for days.

The New Jersey Shore, an iconic vacation area in the Northeast, sufferedworst of all. For almost 150 years, people from hot, crowded citieshave flocked to the Shore to lie on its beaches, families often going to thesame place for generations. They eat ice cream and pizza, play in arcadesonce used by their grandparents, drink in bars, and go to church.The Shore could be a seedy place, fraught with racial tensions, andsometimes crime and violence, but there was always something foreverybody, be they a wealthy resident of a mansion, a contestant in a MissAmerica pageant, a reality TV actor, a skinny-dipper, or a musician.Bruce Springsteen grew up along the Shore and his second album featuredthe song "4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)," an ode to a girl ofthat name and the Shore. "Sandy, the aurora is rising behind us; the pierlights our carnival life forever," he sang. The words have taken on newmeaning since the hurricane came.

Fortunately, the residents were warned in advance of the storm. Theywere advised to evacuate their homes as early as October 26. Two dayslater, the order became mandatory. New Jersey governor Chris Christiealso ordered the closure of Atlantic City's casinos, a decision that provedwise when Sandy swept ashore with brutal force, pulverizing long-establishedbusinesses, boardwalks, and homes. Atlantic City started atrend when it built its first boardwalk in 1870 to stop visitors from trackingsand into hotels. Boardwalk amusements are big business today,many of them faced by boardwalks that are as much as a 0.8-kilometerfrom the waves. Now many of the Shore's iconic boardwalks are history.The waves and storm surge destroyed a roller coaster in Seaside Heights; itlay half submerged in the breakers. Seaside Heights itself was evacuatedbecause of gas leaks and other dangers. Piers and carousels vanished; barsand restaurants were reduced to rubble. Bridges to barrier islands buckled,leaving residents unable to return home. The Shore may be rebuilt,but it will never be the same. A long-lived tradition has been interrupted,perhaps never to return. For all the fervent vows that the Shore will riseagain, no one knows what will come back in its place along a coastlinewhere the ocean, not humanity, is master.

As the waters of destruction receded, they left $50 billion of damagebehind them, and a sobering reminder of the hazards millions of peopleface along the densely populated eastern coast of the United States.Like Hurricanes Katrina in 2005 and Irene in 2011, Sandy showed us inno uncertain terms that a higher incidence of extreme weather eventswith their attendant sea surges threaten low-lying communities alongmuch of the East Coast—from Rhode Island and Delaware to the Chesapeakeand parts of Washington, DC, and far south along the Carolinacoasts and into Florida, which escaped the full brunt of Sandy's fury.There, high winds and waves washed sand onto coastal roads and therewas some coastal flooding, a warning of what would certainly occurshould a major hurricane come ashore in Central or Southern Florida—andthe question is not if such an event will occur, but when.

One hundred and twenty meters and climbing: that's the amount ofsea level rise since the end of the Ice Age some fifteen thousand yearsago. Slowly, inexorably, the ascent continues in a warming world. Todaythe ocean laps at millions of people's doorsteps—crouched, ready towreak catastrophic destruction with storm-generated sea surges andfloods. We face a future that we are not prepared to handle, and it'squestionable just how much most of us think about it. This makes thelessons of Katrina, Irene, and Sandy, and other recent storms importantto heed. Part of our understanding of the threat must come froman appreciation of the complex relationship between humanity and therising ocean, which is why this book begins on a low land bridge betweenSiberia and Alaska fifteen thousand years ago ...

Between Siberia and Alaska, late summer, fifteen thousand yearsago. A pitiless north wind fills the air with fine dust that masks the pale-bluesky. Patches of snow lie in the shallow river valleys that dissect thefeatureless landscape. A tiny group of humans trudge down the valleyclose to water's edge, the wind at their backs, the men's eyes constantlyon the move, searching for predators. They can hear the roar of theocean in the shallow bay, where wind squalls whip waves into a whitefrenzy. A few days earlier, the women had trapped some arctic ptarmiganwith willow snares, but the few remaining birds hanging at theirbelts are barely enough for another meal. A dark shadow looms throughthe dusty haze—a solitary young mammoth struggling to free itselffrom mud at river's edge.

The men fan out and approach from downwind, scoping out the prospectsfor a kill. The young beast is weakening rapidly after days in themuddy swamp. Nothing is to be gained by going in for the kill at themoment, so the band pitches camp a short distance away and lights alarge fire to keep away predators. A gray, bitterly cold dawn reveals thehelpless mammoth barely clinging to life, mired up to its stomach. Ayoung man leaps onto the beast's hairy back and drives his stone-tippedspear between its shoulder blades, deep into the heart. He jumps off toone side, landing in the mud. The hunters watch the mammoth's deaththroes and thrust more spears into their helpless prey. Soon everyonemoves in to skin the flanks and dismember the exposed parts. A shortdistance away, wolves lurk, ready to move in when the humans leave.

Back in camp, the men build low racks of fresh mammoth bone andlay out strips of flesh to dry in the ceaseless wind, while the women andchildren cook meat over the fire. Around them, the dust-filled gloomnever lifts, the wind blows, and the roar of the ocean never leaves theirconsciousness. The sea is never a threat, for their lives revolve aroundthe land and they can easily avoid any encroaching waves by doing whatthey always have done—keeping on the move.

This imagined mammoth hunt unfolded at a time when the world wasemerging from a prolonged deep freeze. The bitter cold of a long glacialcycle had peaked about seven thousand years earlier, the most recent ofa more than 750,000-year seesaw of lengthy cold and shorter interglacialperiods driven by changes in the earth's orbit around the sun, whichhad began 2.5 million years ago. Twenty-one thousand years ago, worldsea levels were just under 122 meters below modern shorelines. The seaswere beginning to rise fast, as a rapid thaw began and glacial meltwaterflowed into northern oceans. Soon one would need a skin boat to crossfrom Siberia to Alaska and the mammoth hunters' killing groundswould be no more.

An ascent of 122 meters is a long way for oceans to climb, but climbit they did, most of it with breathtaking rapidity by geological standards,between about fifteen thousand years ago and 6000 B.C.E. Mostof the ascent resulted from powerful meltwater pulses that emptiedenormous quantities of freshwater from ice sheets on land into northernwaters and around Antarctica. This was not, of course, the first timethat such a dramatic rise had transformed an ice-bound world, but therewas an important difference fifteen millennia ago. For the first time, significantnumbers of human beings, perhaps as many as hundreds of thousandsof them, lived in close proximity to the ocean.

Some traveled offshore. Fifty thousand years ago, even while the lateIce Age was at its height, small numbers of Southeast Asians had alreadyventured into open tropical waters to what are now Australia andNew Guinea. Well before twenty thousand years ago, people were livingon the islands of the Bismarck Strait in the southwestern Pacific. Thesevoyages took place long before melting ice sheets and rising sea levelstransformed the Ice Age world of Homo sapiens.

We live in a rapidly warming world, where human activities now playa significant part in long-term climate change and have done so since theIndustrial Revolution, when fossil fuels like coal came into widespreaduse. It's hard for us to imagine just how different the world was twenty-onethousand years ago. Much of it lay under thick ice. Two huge icesheets covered virtually all of North America, from the Atlantic to thePacific. The Cordilleran ice sheet, centered on the Rockies and westerncoastal ranges, mantled 2.5 million square kilometers. The enormousLaurentide ice sheet lapped the Cordilleran in the west and covered over13 million square kilometers of what is now Canada. It was nearly 3,353meters thick over Hudson Bay. Its southern extremities covered the GreatLakes and penetrated deep into today's United States. The Greenland icesheet was 30 percent larger than today. Another smaller ice sheet linked itto the northern margins of the Laurentide.

In northern Europe, the Scandinavian ice sheet extended from Norwayto the Ural Mountains over an area of 6.6 million square kilometers,may even have reached Spitsbergen, and flowed over much of thenorth German Plain. A smaller ice sheet covered about 340,000 squarekilometers and reached halfway down the British Isles. Glaciers descendedclose to sea level in the Southern Alps. In Siberia and NortheastAsia, ice extended over at least ten times the area of the British ice sheet.Extensive ice sheets mantled the Himalayas.

The Antarctic ice sheet was about 10 percent larger; seasonal sea iceextended eight hundred kilometers out from the continent. There wereimportant ice sheets on the Andes Mountains, in South Africa, southernAustralia, and New Zealand. Twenty-one thousand years ago, therewas two and a half times as much ice on land as there is today. Of that,35 percent was on North America, 32 percent on Antarctica, and 5 percenton Greenland. Today, 86 percent of the world's continental ice is onAntarctica, 11.5 percent on Greenland.

There was so much water locked up in glacial ice sheets and suckedout of the oceans that global sea levels were up to 122 meters belowthose of today. These much lower sea levels changed the shape of entirecontinents. Perhaps most significant historically was the bitterly coldand low-lying Bering Land Bridge that linked Siberia and Alaska, anatural highway that brought the first humans to the Americas. Dryland joined islands in Southeast Alaska and the Pacific Northwest ofNorth America. Much farther south, San Francisco's Golden Gatechannel was a narrow tidal gorge with fast-moving rapids. Continentalshelves extended some distance off the Southern California coast, leavingbut eleven kilometers of open water between the mainland and theChannel Islands close offshore.

On the other side of the Pacific, low sea levels joined the Japaneseislands to Sakhalin Island in the north and brought them much closerto the Chinese and Korean mainland. In China, major rivers like theHuang He in the north and the Yangtze in the south flowed throughincised, narrow valleys rather than broad floodplains. Rolling plainsstretched far into the distance off Southeast Asia. Only short stretchesof open water separated the mainland from Australia and New Guinea,which were a single landmass, now covered by the shallow Arafura Sea.

The configuration of the Indian Ocean was much different from today.Bangladesh lay far above sea level by modern standards, incised bythe Ganges and other rivers that flowed much more rapidly to the sea.Sri Lanka's twenty-nine-kilometer-long Rama's Bridge, now a chain oflimestone shoals, was a land bridge to India. The Persian Gulf was dryland, an arid landscape bisected by a narrow gorge that drained thehighlands and plains at its head.

Had one looked down from a satellite at Europe and the Mediterraneaneighteen thousand years ago, one would have surveyed unfamiliarlandscapes. Continental shelves extended far into the Bay of Biscay. Youcould walk from Britain to France, had you possessed a canoe to carryyou across an enormous estuary that carried the waters of the Rhine,Seine, and Thames Rivers of today. The southern North Sea was a landof shallow lakes and marshes. The Mediterranean was far smaller, itsnarrow entrance at the Strait of Gibraltar scoured by fast-running currents.The northern Aegean Sea ended in a high barrier that isolatedwhat is now the Black Sea from the ocean. The Euxine Lake, formed byglacial and freshwater runoff from the north, lay behind the naturalberm. On the other side of the Mediterranean, the arid Nile delta withits sand dunes extended far into what is now open sea.

Everywhere large rivers like the Thames and the Rhine had lowercourses and estuaries far different from those of today. The Nile flowedthrough a twisting, narrow gorge, where the annual flood for the mostpart remained close to the river channel rather than spilling over a widefloodplain as it did until the building of the Aswan Dam. In the Americas,the St. Lawrence River did not exist; it was under the Laurentide icesheet. The Mississippi and Amazon Rivers cut far below their moderngradients, with almost none of the ponding and wetland formation thatdeveloped as sea levels rose.

Rapid, natural global warming transformed the late Ice Age worldinto what was effectively an entirely different place in less than ten thousandyears. Within this brief time frame, the world's sea levels rose 122meters.

Eustacy and isostasy: the words used to describe sea level changesglide easily off the tongue, but they mask very complex and still onlypartially understood geological processes. What does cause the world'ssea levels to rise and fall? Isostatic changes result from local upward anddownward shifts in the lithosphere, the uppermost layers of the earth.Such factors as earthquake activity and shifts of tectonic plates far belowthe earth's surface are important contributors to sea level change. Subsidencein river deltas, changes in glaciers, even sediment compaction—anythingthat adds to or subtracts from the weight of the earth's crust—allcan cause isostatic sea level rises, such as are common in places likeShanghai.

Eustatic, global sea level rise is completely different, a mea sure of theincrease in the volume of water in the oceans expressed as a change inwater height. Everyone knows that water expands as it heats. When theearth's atmosphere warms, the ocean absorbs much of the increasing heatand its waters swell. Thermal expansion is the major cause of global sealevel rise since the 1860s, when the Industrial Revolution with its promiscuoususe of fossil fuels added more carbon and other pollutants to theatmosphere—in other words, when humanly caused global warming began.At present, eustatic sea level rise advances at a rate of about two millimetersa year if calculated on an average of the past century. Over thepast fifteen years, however, the averaged rate is around three millimeters ayear, apparently a direct, accelerated response to global warming.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from The Attacking Ocean by Brian Fagan. Copyright © 2013 by Brian Fagan. Excerpted by permission of BLOOMSBURY PRESS.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

EUR 8,29 für den Versand von USA nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenEUR 11,56 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für The Attacking Ocean: The Past, Present, and Future...

The Attacking Ocean : The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 4154769-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Attacking Ocean : The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. 1st Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 4189361-75

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Attacking Ocean : The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 4154768-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Attacking Ocean : The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 4154769-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Attacking Ocean: The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.3. Artikel-Nr. G1608196925I4N10

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Attacking Ocean: The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Anbieter: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, USA

hardcover. Zustand: Good. Artikel-Nr. mon0003565167

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Attacking Ocean: The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Artikel-Nr. T06D-02289

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Attacking Ocean: The Past, Present, and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Hardcover. Zustand: Brand New. 1st edition. 288 pages. 9.75x6.50x1.00 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. 1608196925

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Attacking Ocean

Anbieter: Muse Book Shop, DeLand, FL, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: As New. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: As New. 1st Edition. Artikel-Nr. 90902723

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar