Inhaltsangabe

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Jonas Reif is chief editor of german magazine 'Garten Praxis'. He is an experimental landscape designer and passionate gardener. Christian Kress is owner of the Sarastro perennials nursery in Innkreis, Upper Austria. Jurgen Becker, is a multi-award winning garden photographer who lives in Hilden, Germany

Von der hinteren Coverseite

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Once upon a time I bought a plant of Geranium sylvaticum ‘Birch Lilac.' Nine years later, when I moved on from that particular garden, there must have been a hundred of them. It had seeded pretty well all over, so every year May became a haze of violet-blue. It was the perfect seeder, never over-doing it, and crucially, it being a relatively narrow plant, it never swamped anything else. Like many of the best self-seeding effects in gardens its behaviour was not predicted. And like many, when I tried to reproduce it in my next garden, the plant would only self-sow reluctantly.

Allowing and encouraging plants to set seed in the garden and spread themselves around is very much a part of the new garden zeitgeist. Once we planted things and expected them

to stay where they were put. Gardening now is much more accepting of spontaneity, of natural processes of birth, death and decay. Embracing plants that self-seed is part of becoming a manager of nature rather than a controller. Seeding is a vital way in which plant communities thrive and survive. Allowing it in the garden can be seen as a way of the garden becoming an ecological system.

Self-seeding can be a mixed blessing of course. First there is the unpredictability. Although some, like Aquilegia vulgaris, seem to seed in most gardens, most species are not so obliging; they may seed well, or poorly, or not at all, or too much. The latter can be a problem, and there are certainly plants which I now regard as near weeds which started out as desired plants. The winter annual Euphorbia rigida is one. I was thrilled when I first saw seedlings, as I always am when a new plant does this – a sign that the species is at home, and that I have a real dynamic ecological system on my hands. But when the numbers increased, to start to clutter every piece of empty ground within seed-throwing distance of the parent, then I began to regret it, especially as the plants fell over as soon as they flower. Now, almost on the point of eliminating it, I step back from the brink, and let a few survive. In the denser vegetation of what is now a more established garden, they do not seed so much, they have to compete for resources and are more likely to be supported by neighbours. But I will continue to watch them.

Managing the mysteries of self-seeders engages the gardener in the ongoing process of the garden’s own independent life, and is a reminder of the wider world of natural systems, of which the garden can be a tiny and homely example. It is good to have a book that recognises the importance of this vital ecological process. Self-seeding can be a little alarming to the nervous or the novice, and advice from experienced managers of the process is most valuable. —Noel Kingsbury

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Suchergebnisse für Cultivating Chaos: How to Enrich Landscapes with Self-seedin...

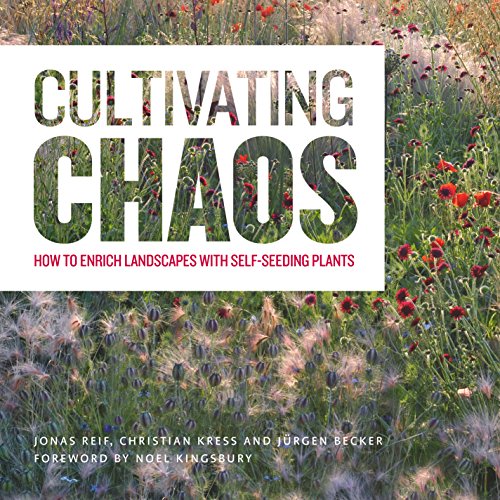

Cultivating Chaos : How to Enrich Landscapes with Self-Seeding Plants

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 17970821-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar