Inhaltsangabe

He was an NFL superstar and Drag Racing icon. He had Hollywood starlets on his arm and a legion of fans in the palms of his hands. Dan Pastorini lived on the edge and palye don the brink. No one-least of all Pastorini-knew what the next turn would bring. His life was indulgent, brilliant, cursed and humbling. He was known a s the toughest man in football, a cover-boy heart-throb and a soft-hearted friend. He changed the way NFL quarterbacks played the game, donning the first Flak Jacket to protect three shattered ribs. He threw perhaps the most fateful pass in playoff history, a controversial championship moment that led to use of NFL replay. He was involved in a tragic speed boating accident. He beat "Big Daddy" Don Garlits and all of drag racing's best. He was the hero in the most triumphant return an NFL team ever received. He never backed down from anything or anyone, falling into notorious scraped and life-altering lows. He married a Playboy model and posed for Playgirl. He dated Farrah Fawcett and was the most iconic figure in a Wild West era when Texas oil boomed and gluttony prevailed. Dan Pastorini never has told the whole story. Until now. This is the story of a gifted, hard-driving kid from California who never stopped going fast or chasing dreams. No matter how much flak he took.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

John is a regular contributor for SportsIllustrated.com and TexAgs.com, as well as co-host of CBS Houston's morning sports talk show, Vandermeer & Lopez. John also has written for the Bryan Eagle, San Antonio Express-News and the Houston Chronicle. He has been named Texas' best sports columnist and earned national recognition from the Associated Press Managing Editors and Associated Press Sports Editors. He has appeared on The Today Show, ESPN Sports Center, Dateline NBC, CNN Sports at Night, CBS This Morning and ESPN's Outside The Lines. He has been a Baseball Hall of Fame voter since 1999 and a Heisman Trophy voter since 1985. In 1997, John co-authored Landing On My Feet - A Diary Of Dreams, with 1996 Olympic gold medalist Kerri Strug. He has three children - Jacob, BG and Leah - and lives in Humble, Tx, with his wife, Jan, and loyal dog, Gibson.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

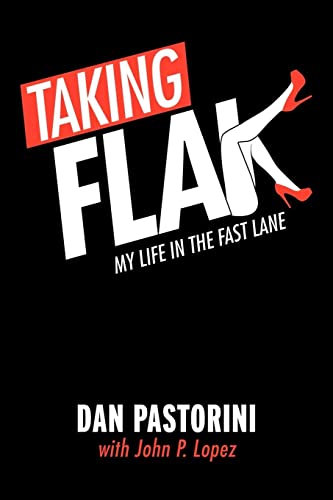

TAKING FLAK

MY LIFE IN THE FAST LANEBy Dan Pastorini John P. LopezAuthorHouse

Copyright © 2011 Dan Pastorini with John P. LopezAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-4670-4468-4

Chapter One

"That kid's got a quarter-million dollar arm."

In the early-fall of 1948, my dad had a hunting accident. My family lived on a beautiful ten acres along Highway 49, near Yosemite Junction, at the foot of the California Sierra Nevada Mountains. Dante Pastorini Sr. sank his life savings into those ten acres, chasing the American dream. On those rare days when dad could get away from working as a butcher, school bus driver, part-time carpenter and one hustling, horse-trading S.O.B., it was hunting that was his passion. Deer hunting, hog hunting, bird hunting. Dad and mom, Dorothy, earned every dollar they made. They busted their asses, bought everything they could with cash, lived modestly and saved the rest. When they finally saved enough to buy a piece of land where they could raise their family near Sonora, Calif., my dad and grandfather, Lou, who immigrated from Tuscany, built a house along a creek at the back of a 10-acre parcel at the foot of the Sierra Nevadas. They built the house by hand, clearing trees, dragging away shale and river rocks, cutting and framing the lumber and running plumbing and electricity lines.

Dad's love for the outdoors probably was the biggest reason he chose to settle his family along that tucked-away piece of Tuolumne County that once was the heart of the California Gold Rush. By 1948 the Gold Rush had long been dead and Highway 49 was well off the beaten path, but dad still had big dreams. He wanted to build and open a restaurant along the front of the property near the highway. A lot of Italian-Americans settled in Tuolumne County after the Gold Rush, which lured my grandfather's family. My Grandmother Irma's family also was from the old country, emigrating from Genoa. Just about every family in Tuolumne County had some kind of roots to the Gold Rush. About $600 million worth of gold eventually was mined from the area between the Sierra Nevadas, Sonora Pass and Tioga Pass. And right in the middle of it all were those ten acres. The Sierra Nevadas literally were at the back door and old, abandoned gold mines, railroad tracks and passes cut in and out of the landscape all around. It was called Yosemite Junction for a reason. It was the pass tourists took to get to Yosemite National Park.

Mom and dad figured tourists and local families needed a good restaurant, where they could stop, get a good meal and enjoy the amazing views. The land was lush, with plenty of wildlife, creeks, brush and all kinds of different trees—oak, pine, maple, dogwood. Sonora may not have been what it once was, but tourists kept it alive. One thing about my dad, he always was thinking. He always had a plan. Mom's biggest hope was the restaurant would keep the family together and living in the country would be perfect for the family to spend a lot of time together. Dorothy, the oldest, was twelve in 1948 and was named after my mother. Annette was seven. And then there was Lou, who everybody called Butch, and was five. It wasn't until my dad finished his hunting trip that day in 1948 that I came into the picture. When dad got home, he realized he spent most of the afternoon sitting in poison oak. He was covered in oil residue from the Poison Oak. It would be just a matter of hours until most of his body would be covered with a rash and he'd be quite uncomfortable for a long time. Those were the days when Poison Oak could last two weeks or maybe even a month or more. It was treated mostly with home remedies—things like oatmeal and baking soda. So my dad brainstormed, as always, and decided to make the most of the situation. He decided he should get amorous with mom before he broke out in the rash, because it might be a while before he could again.

Surprise. Nine months later, I was born Dante Anthony Pastorini Jr. I was the hunting accident, the youngest of four, and five years younger than my nearest sibling. Barely six months after I was born, with an extra mouth to feed that they did not expect or plan, my parents opened Pastorini's Longhorn Club and Café. They came up with the name because dad was kind of a cowboy. He loved horses, always had horses and of course, loved the outdoors. Dad, along with my grandfather and some friends built the restaurant at the front of our property. It was wood-framed, with hardwood floors and great scenery all-around. There was a big dining room, with a bar in front and a club and banquet room in back. Dad was the butcher, wheeler-dealer and cook. Mom was hostess, ran the kitchen and did some cooking. The kids pitched in busing tables, cleaning the restaurant and helping in the kitchen. I learned to walk in that restaurant and did a little bit of everything as I grew up. I learned to hustle for everything just like my dad, who took pride in being meticulous about everything he did. His knives were like treasures. He sharpened them to the point they sliced through loins of beef like butter. Dad cut a loin of beef so closely there wouldn't be enough meat left on the bone for a dog. He was a master butcher. And none of us could ever touch his knives. Ever. He was crazy obsessive about them. He'd yell at us, telling us we were going to dull the edges. Dad had all the connections for restaurant supplies and equipment, too. He drove into town in his truck, with a tarp over the bed. He came back with crates of produce, supplies for the restaurant and sides of beef that he would cut himself. He traded crates of this for crates of that. He was a horse-trading son of a gun. He also always found a way to get people into the restaurant. He was proud of his food and it was always good, but he always was thinking of ways to make the place a destination. There were some lean times, especially early when the club at the back of the restaurant was closed just three months after the restaurant opened. The Feds came in and shut it down, because all clubs were getting licensed and were under scrutiny because of changing gambling laws.

Even though some times were tougher than others, we never lacked. We did learn the value of a dollar, certainly. When dad realized neither the seasonal tourism nor just 1,300 people living in Sonora was enough to sustain the restaurant, he cleared a piece of our property and put in a small rodeo arena. It fit in perfectly with the cowboy theme of the restaurant. He bulldozed an oval, cleared the land and put up a fence. We always had horses anyway, so dad began having rodeos on Saturdays and Sundays. By the time I was six, Butch and I would spend Saturdays sitting on the fence, roping calves after events, corralling animals and getting people to stop by the restaurant for a steak, some home-style meals or Italian food.

I always looked up to Butch. I thought he was the best athlete in the world, too. We probably were the closest among the kids. Mom had a constant dream of us becoming a certain type of family. She always wanted us to do everything together and be a close family that loved each other unconditionally. But we never were what she dreamed about. We all went to church, worked together and mom made sure we were good Catholics, but we really all started going our own ways at an early age. No one ever really showed a lot of affection in our house, except for mom. Dad never told any of us that he loved us and dad's big shortcoming was his temper. When something didn't go right at the restaurant or there'd be some other problem, he'd scream at my mom or throw something. There was a lot of pressure on him with four kids and the life-changing decision he made to open a business in a town of 1,300 people. He also went way over the top sometimes. Mom took a lot of crap from all of us, in fact. Dorothy and Annette never really got along, always seemed to be jealous of each other and were entirely different types of people. Dorothy was the wild child, going out, smoking, drinking, carousing. Annette was kind of a strange cat. She was just a different personality, kind of plain, with a good old-fashioned Italian nose and a quiet side. My dad teased Annette a lot.

"If I could fill that nose with nickels, I'd be a rich man," he'd tell her.

I guess that's the only way our family knew how to show affection. We teased each other until we cut to the bone.

Butch was short and muscular and the toughest kid around, with a temper like my dad. When I was seven, Butch and I got into a snow ball fight with some kids who were Butch's age. One of the kids put a rock inside a snowball and hit me over the eye with it, cutting my eye pretty good. Butch just exploded. I mean, it was a 20-minute ass-kicking. When the kid got knocked down, Butch picked him back up and beat him some more. All the way down the highway, Butch was beating his ass. I got scared and ran back to the restaurant to tell dad Butch was fighting. As he watched from the porch, dad took a puff of his cigarette and said, "Let him fight."

Then, dad yelled at the kid running up the highway, "Don't ever come back you little son of a bitch, because I'll do it next time."

A few months later, we were clearing another area on the property for a barn. Butch and I were out messing around when Butch went behind a huge oak to cut a willow switch with his pocket knife. A friend of dad's was working a bulldozer, cutting down the oak tree. He never saw Butch standing behind the tree.

When the driver hollered at us to clear the area, my dad thought Butch was with us. Dad grabbed me and said, "Come on, Willie."

Dad always called me Willie because from the moment I saw Willie Mays a couple years earlier in the 1954 World Series, he was my hero. He was my idol. The Say-Hey Kid seemed perfect to me.

When dad and I turned around, Butch wasn't with us. Just as we heard the crack of the tree falling, we saw him behind the tree. It had an L-shaped branch pointing out the back, toward where Butch was standing. Butch ran away when he heard the crack of the tree, but he slipped on some sharp shale rock. The tree hit him and the limb dragged him across the rock. Dad and I ran toward Butch, screaming, "Are you alright? Are you alright?"

"Yeah, I think so."

But when Butch stood up and tried to take a step, the entire quad muscle on his right leg squeezed out the front of his thigh. The shale cut a wide gash up the front of Butch's leg, from the top of his knee, to his hip joint. When he stood up, the skin just laid wide open, like someone sliced open a banana. The gash was so deep; dad and I could see the bone.

Butch was 13-years-old, but he never shed a tear. Right there, I gained so much admiration for Butch and I realized just how tough he was. Eventually, Butch underwent several operations, skin grafts, had his leg set and re-set and had several hundred stitches. The scar was horrible. Naturally, I made fun of it. The next year, Butch wanted to play football and he made the middle school football team basically on one leg. That's the kid I decided I wanted to be like. Dad always bragged about Butch's successes in sports, too. Butch truly set the tone for me. I'd better not cry about anything. I'd better be tough. I'd better be good. Watching my dad admire Butch so much, I always wanted that admiration. I wanted that affirmation from dad.

Even before I started playing organized baseball, I played thousands of imaginary games on our property. We had a creek behind our house and there was every kind of rock imaginable in that creek bed. I was Willie Mays. I pretended I was making the throw from center-field in the 1954 World Series, throwing rocks all the way down the gravel road that ran from the house at the back, to the highway. I pretended to catch a ball over my shoulder, then turned and chunked rocks as far as I could. I did it over and over again. I wrapped tape around old broomsticks from the restaurant and hit rocks from the gravel road over the creek or from the back of the restaurant across the property. I was Willie Mays, bottom of the ninth, throwing rocks up and hitting them. I hunted with rocks, too. I hiked up the Sierra Nevadas with a BB gun and climbed through old mining dumps and up and down rocks and cliffs, shooting mice, or throwing rocks at mice and birds. Butch and I made up a bunch of competitions, too. He was older and better than me at most games, but it didn't take long before I started wearing his ass out. It was about 60-yards from the front of the restaurant to the back and we would see which one of us could throw a rock all the way to the back. By the time I was eight, I was throwing better than Butch, easily throwing a rock over the restaurant. I also started playing organized baseball and it just came easy. I never knew why, but throwing a ball just felt natural, and simple. It also was weird that I couldn't throw with my left hand. I did my homework left-handed, ate left-handed, washed dishes and bused tables left-handed. I did most everything left-handed. But when I picked up a rock, a baseball or a football, I would rear back with my right arm, reach far back behind until my arm was parallel to the ground and sling it overhead with ease. I was a pitcher and shortstop. My first year playing organized baseball, I threw eight no-hitters. My second year, I threw nine. I struck out batter after batter after batter. When I pitched well, dad bragged about me and that's the closest he ever got to telling me he loved me. I craved the attention. When I was in third-grade, I played left-field on my brother's eighth-grade team. Sometimes, I tried to figure out why it was me that was given this gift. As much as I was having fun playing with the older kids, earning a lot of attention, especially from my dad, I felt a little bit of a burden and a responsibility. My dad always told Butch, mom, and just about everyone, "That kid's got a quarter-million dollar arm."

I always wanted to please dad, play well for my coaches and live up to everything that Butch was as a player. The more I pitched in Little League, the harder I threw. The more success I had, the more I threw. It always was to please dad. My dream was to look him in the eye one day and say, "We did it."

Dad never got his chance to make it, even though he was a hell of a baseball player. As a teenager in the 1930s, dad was a catcher for the San Francisco Mission Reds of the Pacific Coast League. He played with guys like Joe DiMaggio and Lefty O'Doul. He loved all kinds of sports, but baseball was No. 1. He was a special player. When he was eighteen, playing at the Double-A level for the Mission Reds, a New York Yankees scout discovered him. After scouting my dad, the scout went to my grandparents' house and talked about bringing dad to New York, putting him in the organization and making a big-league player out of him. He offered my dad a baseball contract, but my grandmother refused to allow dad to sign.

"My son is not going to be a bum," she told dad. "My son is going to get an honest job and make an honest living."

Dad begged his parents to let him play for the Yankees, but they refused. They thought ballplayers were low-class people. They thought ballplayers were uneducated. It always ate at dad that he didn't get his chance. So I wanted to fulfill that dream for him.

To me, my grandparents were crotchety and kind of mean. I knew they did a lot of good things and were good people, but I never really got to know them, because they spoke only Italian. They were first-generation Pastorinis from the Old Country. My sister Dorothy was bilingual, but by the time I was eight, she already was long gone to college. Being the youngest, I never learned anything but a couple of words in Italian. My mother was Irish and she wound up speaking better Italian than dad, but I never talked with my grandparents. All I knew was they were old; they were real tough on dad and never really wanted to spend a lot of time with us kids.

My grandfather died when I was nine. I was outside playing by myself near the creek. I was throwing rocks behind a huge walnut tree, when I heard someone come outside the back of the restaurant. It was dad and he was crying. I ducked behind the tree. I was just scared, because I'd never seen my father cry before. This was my hero. This was the strongest man I knew. And he just kept crying. I finally walked up to him and put my arm around him. He kept weeping. I asked what was wrong and he told me his father died.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from TAKING FLAKby Dan Pastorini John P. Lopez Copyright © 2011 by Dan Pastorini with John P. Lopez. Excerpted by permission of AuthorHouse. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Taking Flak: My Life in the Fast Lane

Taking Flak : My Life in the Fast Lane

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 12559759-6

Taking Flak : My Life in the Fast Lane

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 45895495-6

Taking Flak: My Life In The Fast Lane

Anbieter: Books End Bookshop, Syracuse, NY, USA

Trade Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: None. 9.0 X 6.0 X 0.6 inches; 260 pages. Artikel-Nr. 448713

Taking Flak: My Life in the Fast Lane

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. 248 pages. 9.00x6.00x0.75 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. 1467044687

Neu kaufen

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar