Inhaltsangabe

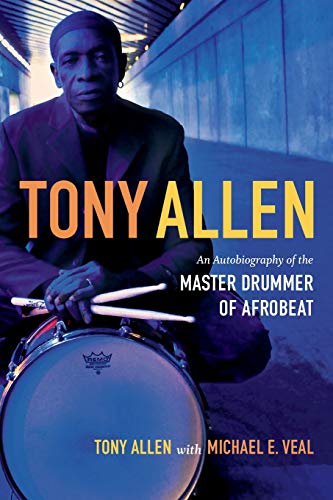

is the autobiography of legendary Nigerian drummer Tony Allen, the rhythmic engine of Fela Kuti's Afrobeat. Conversational, inviting, and packed with telling anecdotes, Allen's memoir is based on hundreds of hours of interviews with the musician and scholar Michael E. Veal. It spans Allen's early years and career playing highlife music in Lagos; his fifteen years with Fela, from 1964 until 1979; his struggles to form his own bands in Nigeria; and his emigration to France.

Allen embraced the drum set, rather than African handheld drums, early in his career, when drum kits were relatively rare in Africa. His story conveys a love of his craft along with the specifics of his practice. It also provides invaluable firsthand accounts of the explosive creativity in postcolonial African music, and the personal and artistic dynamics in Fela's Koola Lobitos and Africa 70, two of the greatest bands to ever play African music.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Tony Allen, a major African musician and world-class drum-set player, was born in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1940 and has lived in Paris since 1985. Allen is best known as Fela Kuti's supremely talented sideman. After leaving Fela's band Africa 70 in 1979, Allen went on to establish a successful career as an independent musician. During his five decades behind the drum set, he has toured the globe and collaborated with musicians from King Sunny Adé to Ginger Baker to Damon Albarn.

Michael E. Veal is a musician and Professor of Music and African American Studies at Yale University. He is the author of Fela: The Life and Times of an African Musical Icon.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

TONY ALLEN

An Autobiography of the MASTER DRUMMER OF AFROBEAT

By TONY ALLEN, MICHAEL E. VEALDuke University Press

All rights reserved.

Contents

| acknowledgments............................................................ | ix |

| introduction by Michael E. Veal............................................ | 1 |

| chapter one RIGHT IN THE CENTER OF LAGOS................................... | 21 |

| chapter two HIGHLIFE TIME.................................................. | 36 |

| chapter three THE SKY WAS THE LIMIT........................................ | 47 |

| chapter four GOD'S OWN COUNTRY............................................. | 68 |

| chapter five SWINGING LIKE HELL!........................................... | 85 |

| chapter six EVERYTHING SCATTER............................................. | 108 |

| chapter seven PROGRESS..................................................... | 128 |

| chapter eight WHEN ONE ROAD CLOSE ......................................... | 146 |

| chapter nine PARIS BLUES................................................... | 162 |

| chapter ten NO END TO BUSINESS............................................. | 175 |

| selected references........................................................ | 187 |

| index...................................................................... | 193 |

CHAPTER 1

RIGHT IN THE CENTER OF LAGOS

I was born Tony Oladipo Allen in Lagos on July 20, 1940,and I grew up in the area called Lafiaji, right in the center ofLagos Island. My family lived at number 15, Okusuna Street.Lafiaji was a good area. It was very near to what we calledthe Race Course in those days. Today they call it Tafewa BalewaSquare. King's College is in that area, too. Later on, my familymoved to Ebute-Metta, on the mainland.

My father's name was James Alabi Allen. He was a Nigerian,a Yoruba from Abeokuta. We don't exactly know how the name"Allen" came into my father's family, but it's probably a slaver'sname. It must have come either from my great-grandfather orfrom his own father, because one of them was among thosepeople rescued by the British slave patrols in Sierra Leone.Many of the slaves that were taken from Nigeria and rescuedby the slave patrols—especially the Egbas that were taken fromAbeokuta—they would drop them in Sierra Leone. That's whytoday my father's family still has a place in Sierra Leone. I rememberthat once when I was arriving in Britain, the immigrationofficer looked at me suspiciously and asked where I got thename "Allen." I just looked at him and laughed and told him, "Iwish I could know my real name. Because the name 'Allen' iscoming from you guys. You gave me my name, historically, sowhy are you asking me where I got this name from?" He kept hismouth shut after that.

My father's father, Adolphus Allen, was a prominent man in Lagos.Allen Avenue in Ikeja is named after him. I don't know too much abouthim because I was only two years old when he died. What I do know isthat he was a clergyman who founded a church called Bethel Cathedral,which is on Broad Street on Lagos Island. Before that he was a policeman,and he must have passed through some hard things working withthe white guys back then, because it was his will that none of his childrenwould become policemen, and none of them did. My grandfather alsoowned a big piece of farmland in Ikeja, on the outskirts of Lagos. Thatland was later sold by my father and his brothers to the Lagos State government,and the government built the Airport Hotel on it. It was alsopart of that land, but on the other side of Obafemi Awolowo Way, thatmy father sold to Fela years later. In the old times, that was the smallerpart of the farm.

My mother's name was Prudentia Anna Mettle. She was born in Lagosas one of the daughters of the Ghanaian settlers in those days. Her parentsand grandparents had settled in Nigeria way back, probably in the1800s. My mother's mother was from Keta, Ghana. So my mother spokeGa and Ewe, and believe it or not, she could even speak Yoruba betterthan my father! As for me, I grew up in Lagos speaking Ga, Ewe, andYoruba. In those times, most of the Ghanaian settlers were fishermen,and they lived on Victoria Island. Back in the old days, Victoria Island wasa real fishermen's village. Think about environments like Hawaii with allthe beaches and fishermen's huts—that is what Victoria Island was likebefore they developed it into what it is today.

There were six of us children in all, and I am the oldest one. The oneright under me is my brother Adebisi. He's an aeronautics engineer,working for British Airways in London and Lagos. The next one afterhim is my brother Olatunji, who is a civil servant in London. After himis my brother Olukunmi, who is a doctor in London. After Olukunmi ismy sister Jumoke, who is a head nurse in Boston, in the United States.And the baby of us all is my sister Enitan, who is a trader in Lagos, inthe market. I also have a half-brother from my father. He's called Tundeand he's a mechanic in Germany. Since I myself have been in Paris fortwenty-five years, you can see that we have all spread out from Nigeria,across the world.

We all have Yoruba names, but since our mother was from Ghana, weeach have a Ghanaian name too. For example, my brother Adebisi is alsocalled Kofi, and my sister Enitan is also called Afi. As for me, there arepeople in Lagos today who still know me as Kwame, because I was bornon a Saturday and that's the customary name in Ghana if you were bornon that day. My family on my mother's side all call me Kwame.

Maybe being a "dual breed" like that is why I've always done my ownthing. I've always been independent. Like when it comes to clothes, I'msomebody that always liked dressing casually, ever since I was young. Isimply like casual dressing. But it was the pride of all my colleagues I wasgrowing up with to have these fancy Yoruba attires, these big agbadas andall that stuff. If you want to talk about our own traditional Yoruba clothing,you have to have about three layers to put on, maybe four. First youput on the normal singlet (sleeveless undershirt) underneath, for the perspiration.Then you put on the one called buba. That's the one with shortsleeves. After that you put dansiki on top, which is the third layer. Andstill, you must put agbada on top of that. Then it's complete. And somepeople can even put some lighter materials on top of that! That's the tradition.Even all of my brothers love it. But for me, I prefer to pick what Ilike, dress casually, and go by my own style. I mean, dressing is not reallypart of what I think about. I can dress elegantly if I want to. But I'm notreally putting a lot of energy into styles and all that. I just want to be comfortable,that's all.

But the Yorubas are really into conformity. For example, every timewhen there is any occasion, like a funeral or whatever, they have to celebrateand throw a big party. And every group at the party has to have veryspecific garments. Like maybe this side is the mother's side of family.The family will tell them that they should dress in a certain style. Andthen on the father's side, they will tell them to choose another style. Thefamily will bring the sample cloth out to the family and tell you,...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Tony Allen: An Autobiography of the Master Drummer...

Tony Allen: An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0822355914I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Tony Allen

Anbieter: PBShop.store UK, Fairford, GLOS, Vereinigtes Königreich

PAP. Zustand: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Artikel-Nr. FW-9780822355915

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 15 verfügbar

Tony Allen

Anbieter: Majestic Books, Hounslow, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: New. pp. 232. Artikel-Nr. 57093572

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 3 verfügbar

Tony Allen An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. 232 pages. 9.00x6.00x0.75 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. x-0822355914

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Tony Allen: An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat

Anbieter: Kennys Bookstore, Olney, MD, USA

Zustand: New. 2013. Illustrated. Paperback. . . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Artikel-Nr. V9780822355915

Neu kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar

Tony Allen: An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Kartoniert / Broschiert. Zustand: New. Tony Allen is the autobiography of legendary Nigerian drummer Tony Allen, the rhythmic engine of Fela Kuti s Afrobeat.Über den AutorTony Allen, with Michael E. VealInhaltsverzeichnisAcknowledgments ix. Artikel-Nr. 595070094

Neu kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Tony Allen : An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat

Anbieter: AHA-BUCH GmbH, Einbeck, Deutschland

Taschenbuch. Zustand: Neu. Neuware - Tony Allen is the autobiography of legendary Nigerian drummer Tony Allen, the rhythmic engine of Fela Kuti's Afrobeat. Conversational, inviting, and packed with telling anecdotes, Allen's memoir is based on hundreds of hours of interviews with the musician and scholar Michael E. Veal. It spans Allen's early years and career playing highlife music in Lagos; his fifteen years with Fela, from 1964 until 1979; his struggles to form his own bands in Nigeria; and his emigration to France. Artikel-Nr. 9780822355915

Neu kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Tony Allen | An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat

Anbieter: preigu, Osnabrück, Deutschland

Taschenbuch. Zustand: Neu. Tony Allen | An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat | Tony Allen | Taschenbuch | Einband - flex.(Paperback) | Englisch | 2013 | Duke University Press | EAN 9780822355915 | Verantwortliche Person für die EU: Libri GmbH, Europaallee 1, 36244 Bad Hersfeld, gpsr[at]libri[dot]de | Anbieter: preigu. Artikel-Nr. 121030489

Neu kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar