Inhaltsangabe

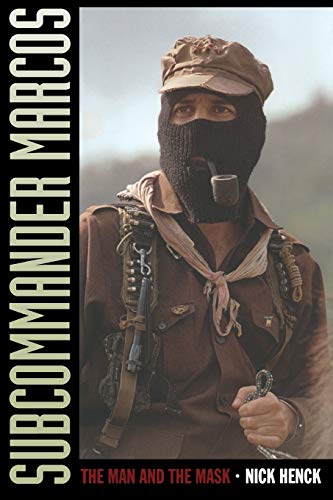

Subcommander Marcos made his debut on the world stage on January 1, 1994, the day the North American Free Trade Agreement took effect. At dawn, from a town-hall balcony he announced that the Zapatista Army of National Liberation had seized several towns in the Mexican state of Chiapas in rebellion against the government; by sunset Marcos was on his way to becoming the most famous guerrilla leader since Che Guevara. Subsequently, through a succession of interviews, communiquÉs, and public spectacles, the Subcommander emerged as a charismatic spokesperson for the indigenous Zapatista uprising and a rallying figure in the international anti-globalization movement.

In this, the first English-language biography of Subcommander Marcos, Nick Henck describes the thought, leadership, and personality of this charismatic rebel spokesperson. He traces Marcos’s development from his provincial middle-class upbringing, through his academic career and immersion in the clandestine world of armed guerrillas, to his emergence as the iconic Subcommander. Henck reflects on what motivated an urbane university professor to reject a life of comfort in Mexico City in favor of one of hardship as a guerrilla in the mountainous jungles of Chiapas, and he examines how Marcos became a conduit through which impoverished indigenous Mexicans could communicate with the world.

Henck fully explores both the rebel leader’s renowned media savvy and his equally important flexibility of mind. He shows how Marcos’s speeches and extensive writings demonstrate not only the Subcommander’s erudition but also his rejection of Marxist dogmatism. Finally, Henck contextualizes Marcos, locating him firmly within the Latin American guerrilla tradition.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Nick Henck is Visiting Associate Professor in the Faculty of Law at Keio University in Tokyo.

Von der hinteren Coverseite

"In this encyclopedic biography, Nick Henck draws on almost everything ever published on Subcommander Marcos. The result is an analysis that first highlights Marcos's intellectual and political formation prior to his entering the Lacandon jungle in late 1983, and then illuminates the Subcommander's unique cultural and political flexibility, which ultimately served to let the EZLN be directed by the priorities of the indigenous communities of Chiapas. As Henck points out, this flexibility is what distinguished Marcos from other twentieth-century guerrilla leaders; it was pivotal in permitting the EZLN to play a central role in the democratization of Mexico after seventy years of one-party rule. This is a valuable reference book for all those interested in a detailed account of the rise of Subcommander Marcos and the EZLN in Chiapas."--Lynn Stephen, author of "Transborder Lives: Indigenous Oaxacans in Mexico, California, and Oregon"

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

SUBCOMMANDER MARCOS

The Man and the MaskBy NICK HENCKDuke University Press

Copyright © 2007 Duke University PressAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-8223-3995-3

Contents

Illustrations.............................................................xiAcknowledgments...........................................................xiiiAbbreviations and Acronyms................................................xvCast of Main Characters...................................................xixIntroduction..............................................................11. Birth and Family.......................................................132. School Years...........................................................203. High School College....................................................234. UNAM...................................................................295. The Graduate...........................................................426. Chiapas................................................................577. Guerrilla Inception....................................................658. The Wilderness Years...................................................769. First Contact..........................................................8210. Promotion and Expansion...............................................8811. A Jungle Wedding......................................................10712. An Election, Exponential Growth, and a Rift...........................11213. Bust and Boom.........................................................12414. Fallout...............................................................12915. From the People's Guerrilla to a Guerrilla People.....................13316. Indigenous Indignation................................................14317. An Internal Coup and the Road to War..................................16318. The Uprising..........................................................19519. "Waging a Masterful Media War"........................................21320. A Cease-Fire..........................................................22121. The Cult of Marcos....................................................22622. Peace Talks...........................................................24723. Courting Civil Society................................................25324. The Elections and Their Aftermath.....................................26225. Marcos Unmasked and Rafael Revealed...................................27826. Nationalizing and Internationalizing the Struggle.....................30127. A March and a Massacre................................................31528. Speedy Gonzalez Breaks the Silence....................................32129. A Consulta, a Story, and a Strike.....................................33030. A Change of Government................................................33631. The Zapatour..........................................................34232. Marcos Today..........................................................353Conclusion................................................................361Notes.....................................................................369Glossary..................................................................467Works Cited...............................................................469Index.....................................................................487

Chapter One

Birth and Family

Rafael Sebastin Guilln Vicente was born in Tampico on 19 June 1957 into a family that neighbors have described as "part of [Tampico] society though not high society." Tampico is in the state of Tamaulipas-famous for its seafood and its cyclones-on the Gulf of Mexico. In the 1950s it was a bustling tropical port; in the early part of the twentieth century it had been the busiest oil port in the world. In hindsight it seems ironic that in the 1930s government money had been diverted away from public building projects (such as reservoirs) in Chiapas and toward Tampico: the consequential stunting of Chiapas's development would provide Rafael, a middle-class scion of the beneficiary city, with a setting and support base for his career as a revolutionary.

Rafael's date of birth is highly significant, coinciding with the emergence of left-wing guerrilla insurgency based on the foco. The year 1957 saw Che Guevara and Fidel and Raul Castro fighting their way through the Sierra Maestra toward Havana in neighboring Cuba. (They had arrived on Cuban soil on 2 December 1956, having sailed from Tuxpn, only 94 miles [151 km] down the coast from Tampico.) One month after Rafael's birth, on 21 July, Guevara became the first combatant to be promoted to comandante and was given command of the second column (called Column 4 in order to confuse the enemy). Rafael's most impressionable years (ten to eighteen) witnessed the death of Guevara (October 1967); the year of revolution (1968), including the Paris student uprising and the massacre of students in Mexico City at Tlatelolco (2 October 1968); and the severe repression unleashed by the Echeverra government against left-wing militant groups (the early and mid-1970s). It is not hard to imagine the impact of such events on the media and thus, consequently, on a politically minded family. Marcos states that as a family, "We learnt to read, not so much in school, as in the columns of newspapers." These happenings probably resulted in Rafael's first exposure to and participation in intense political discussion. Such family debate must have formed a lasting impression on him. Significantly, in the immediate aftermath of Tlatelolco, the student leader Eduardo Valle prophesied:

I think the Movement will have its effect on the children.... In generations that lived it ... seeing their older brothers move ... into action, hearing stories of the days of terror, feeling them in their blood ... the government of this country will have to be very wary of those who were ten or fifteen in 1968 ... they will always remember the assaults upon, the murders of their brothers.

Rafael, at that time aged eleven, proved to be just such a child, going on later to fulfill this prophecy by becoming the greatest thorn in the sides of the Salinas and Zedillo governments.

The impact of Tlatelolco on Rafael is made explicit in Marcos's communiqu Tlatelolco: Thirty Years Later the Struggle Continues, dated 2 October 1998 and addressed "to the Generation of Dignity of 1968." It was written to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the massacre, and, in addition to saluting those who died or felt the pain of 1968 and demanding "that the whole truth be told, that yesterday's and today's crimes no longer go unpunished," Marcos lays claim to being part of the same tradition as those who rebelled in 1968, the tradition of resistance. While admitting that the Zapatistas are "different and distinct" from those who resisted thirty years previously, the enemy is portrayed as the same, with the free-standing line "1968.1998," designed to highlight the fact that nothing had changed, comprising four of the final fifteen lines of the communiqu. Further evidence of the impact of Tlatelolco on Rafael can be seen in a February 1994 interview with La Jornada correspondents. The journalists asked him, "Generationally speaking, are you a product of '68?" Marcos replied: "I'm definitely post-'68, but not the core of '68 ... I was a little kid. But I do come from everything that followed, especially the electoral frauds, the most scandalous one in 1988, but others as well."

Ten days after the student massacre, Mexico hosted the Olympic Games (12-27 October 1968). Marcos subtly plays on the near coincidence of these two occurrences in his Tlatelolco communiqu, where he talks of the "olympic astonishment and shame that beheld the [Tlatelolco] massacre." The Games, no doubt, also impacted on Rafael, who later enjoyed sports, especially basketball. The 1968 Olympics also proved memorable politically for the discussion provoked by the controversial Black Power salute made by the U.S. athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos.

Just as people are partly a product of the era into which they were born, so they are also partly a product of the families in which they were raised. Rafael, like Lenin, was the fourth of eight children. He had six brothers and one sister, all of whom went on to attend university. His sister, Mercedes del Carmen Guilln Vicente, also known as "Paloma," obtained a degree in law and economics. Alfonso earned a degree in business management and subsequently became a professor of Mexican history at Universidad Autnoma de Baja California Sur. Hctor also earned a degree in business management. Carlos obtained a degree in sociology at Mexico City's National Autonomous University (UNAM), and he later went on to become a federal government accounting officer. He died of asphyxia in July 1994 at age thirty-eight; he had had epilepsy from childhood. Rafael also obtained his degree, in philosophy and arts, at UNAM. David's degree was in agricultural engineering, Sergio's was in mathematics, and Fernando's was in public finance and accountancy.

The fact that Rafael was the fourth of eight children is perhaps of some consequence. Much research has been undertaken recently on the effect birth order has on personality. The eminent sociologist Frank J. Sulloway has studied birth order for twenty years and recently finished a study in which he used more than half a million data points mined from tens of thousands of biographies relating to the lives of 6,000 individuals. He concluded that "some people, it seems, are born to rebel." Sulloway argues that birth order (whether you are the firstborn child or a later-born child) greatly shapes your propensity to rebel. He argues that "siblings become different for the same reason that species do over time: divergence minimizes competition for scarce resources." Elaborating on this, he adds:

Siblings compete with one another in an effort to secure physical, emotional, and intellectual resources from parents. Depending on differences of birth order, gender, physical traits, and aspects of temperament, siblings create differing roles for themselves within the family system. These differing roles in turn lead to disparate ways of currying parental favor.... As children become older and their unique interests and talents begin to emerge, siblings become increasingly diversified in their niches. One sibling may become recognized for athletic prowess, whereas another may manifest artistic talents. Yet another sibling may be good at mediating arguments and become the family diplomat.

According to Sulloway, "Revolutionaries owe their radicalism to competition for limited family resources-and to the niches that characterize such competition-not to class consciousness."

Of direct relevance to Marcos, Sulloway argues that "laterborns are more likely to identify with the underdog and to challenge the established order" and that "their hearts and souls are most thoroughly identified with radical changes that defy the status quo." They characteristically possess an "openness to experience, a dimension that is associated with being unconventional, adventurous, and rebellious." They tend "as family underdogs ... to empathize with other downtrodden individuals and generally support egalitarian social changes ... to be more adventurous than firstborns ... [and] to question authority and to resist pressure to conform to a consensus." In his conclusion, Sulloway states: "In Western history, laterborns have been eighteen times more likely than firstborns to champion radical political revolutions." He points out that Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, and Castro were all laterborns, although interestingly Guevara, a firstborn, was not. Firstborns, on the contrary, "identify more strongly with power and authority [since] they arrive first within the family and employ their superior size and strength to defend their special status." It is interesting to note that the Guillns' second child, their only daughter, Paloma, conforms to this pattern, having become a deputy and delegate of the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional) XV district in 1984 and marrying Jos Mara Morfin (advisor to the governor for the state of Puebla) in 1993. She and her husband were subsequently awarded the certificate of good conduct by the governor of Puebla, Manuel Bartlett, for their services to the PRI.

Sulloway's findings concerning middle children-to which category both Marcos and Fidel Castro belong-are even more pertinent. He argues that "when they rebel, they do so largely out of frustration, or compassion for others, rather than from hatred or ideological fanaticism," and that "middle children make the most 'romantic' revolutionaries." This second assertion concerning romanticism had earlier been made by two other scholars, Rejai and Phillips, who reviewed the lives of 135 political leaders forged in 31 rebellions. Rafael's romanticism clearly owes much to his father, Alfonso, who appears to have had the same Quixotic disposition as Che Guevara's father, although as a successful entrepreneur he was clearly blessed with greater business acumen and possibly better fortune, since at its height his furniture business had eight outlets and twenty employees. Alfonso had been a dreamer and a lover of poetry, but after marriage and having a large family he had to attend to the more practical matter of making money to provide for them. He lived out his utopianism vicariously through his son, Rafael, in whom he inculcated "a love of poetry and noble causes" and through whom his idealism lived on. Indeed, his father claims that Rafael, as Marcos, "has restored to me the joy of living, my second youth."

The work by Rejai and Phillips is particularly interesting since it identifies features common to most revolutionaries. They argue, for example, that

revolutionary elites are typically of legitimate birth ... from relatively large families, with over 65 percent having three to nineteen siblings ... are urban born ... tend to enjoy "tranquil" family lives ... [are] middle class [and] of mainstream variety in respect to ethnicity and religion ... [are] well educated (nearly 70 percent have college or professional education) ... have impressive publication records ... [and] are cosmopolitan in many senses; they speak foreign languages, travel far and long ... [and] do not follow either their fathers' profession or the profession for which they were originally trained.

Rafael, as we will see, conforms to this revolutionary elite pattern on every count.

It is perhaps also worth noting that Rafael also conforms to the findings of a recent study on birth order that concluded: "Middleborns seldom name their parents as their closest interactants." The same study also found that when asked "to whom would you turn for emotional support," "middleborns were more than five times as likely to name a sibling than were firstborn or lastborn respondents." This perhaps helps to explain Rafael's especially close relationship with his brother Carlos, with whom he lived at university for three years. The tendency to turn to family members other than parents for emotional support perhaps also explains why, like Che, Rafael was particularly close to his maternal grandmother, Antonia Gonzlez. She had moved from Veracruz to live with the Guilln family when her husband died. She would often look after the children while their mother worked alongside Rafael's father in the family furniture store. Apparently she was an affectionate woman and Rafael grew profoundly attached to her.

Like many high achievers Rafael was a precocious child, his parents having given him a head start by educating him themselves before he went to school. Marcos claims, "I learned to read in my house, not at school; so when I went to school I had a great advantage, because I was already well read." This, however, conflicts with what his father tells us, namely that "before the age of five, without having even learned to read, he already knew how to recite." (He claims to have taught Rafael to recite from memory "El Sembrador," the 495-word poem by Marcos Rafael Blanco Belmonte.) Whatever the truth about Rafael's reading capabilities, it is clear that he was exposed at a young age to learning. This ought not to surprise us, given that his father had worked as a rural teacher for seven years, prior to building his furniture empire. When asked by Gabriel Garca Mrquez where his "considerable literary education of the traditional kind" came from, Marcos replied:

From childhood. In our family words had a very special value. Our way of approaching the world was through language ... Early on, my mother and father gave us books that disclosed other things. One way or another, we became conscious of language-not as a way of communicating, but of constructing something. As if it were a pleasure more than a duty.

He then outlines his boyhood literary diet:

The Latin American boom came first.... My parents introduced us to Garca Mrquez, Carlos Fuentes, Monsivis, Vargas Llosa (regardless of his ideas), to mention only a few. They set us to reading them. A Hundred Years of Solitude to explain what the provinces were like at the time. The Death of Artemio Cruz to show what had happened to the Mexican Revolution. Das de guardar to describe what was happening in the middle classes. As for La cuidad y los perros, it was in a way a portrait of us, but in the nude. All these things were there.... Next came Shakespeare ... then Cervantes, then Garca Lorca, and then came a phase of poetry.... We went straight from the alphabet to literature and from there to theoretical and political texts, until we got to high school.

Marcos believes that as a result of this parental encouragement:

We went out into the world in the same way that we went out into literature. I think this marked us. We didn't look out at the world through a news-wire but through a novel, an essay or a poem. That made us very different. That was the prism through which my parents wanted me to view the world, as others might choose the prism of the media, or a dark prism to stop you seeing what's happening.

In addition to introducing their children to literature, Rafael's parents provided them with a firm grounding in Mexican history. Marcos informs us in one interview that "my parents taught me a lot about Mexican history," adding, "my main influences were Villa, Zapata, Morelos, Hildago, Guerrero: I grew up with these heroes."

As well as developing their children's intellects, Rafael's parents also imbued their offspring with a strong sense of morality. In an interview given in March (but published in June) 1994 Marcos tells us:

My parents taught us that, whatever path we chose, we should always choose el camino de la verdad-the path of truth-no matter how hard it might be, whatever it might cost. That we shouldn't value life over the truth. That it was better to lose your life than to lose truth ... we were taught that all human beings had rights, and it was our duty to fight against injustice.

Excerpted from SUBCOMMANDER MARCOSby NICK HENCK Copyright © 2007 by Duke University Press. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Subcommander Marcos: The Man and the Mask

Subcommander Marcos : The Man and the Mask

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 9358824-6

Subcommander Marcos: The Man and the Mask

Anbieter: Anybook.com, Lincoln, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. This is an ex-library book and may have the usual library/used-book markings inside.This book has soft covers. In good all round condition. Library sticker on front cover. Please note the Image in this listing is a stock photo and may not match the covers of the actual item,850grams, ISBN:9780822339953. Artikel-Nr. 3964905

Gebraucht kaufen

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Subcommander Marcos The Man and the Mask

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. new title edition. 499 pages. 9.25x6.00x1.25 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. x-0822339951

Neu kaufen

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Subcommander Marcos: The Man and the Mask

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Zustand: New. Über den AutorNick Henck is Visiting Associate Professor in the Faculty of Law at Keio University in Tokyo.InhaltsverzeichnisIllustrations xiAcknowledgments xiiAbbreviations an. Artikel-Nr. 595069291

Neu kaufen

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar

Subcommander Marcos : The Man and the Mask

Anbieter: AHA-BUCH GmbH, Einbeck, Deutschland

Taschenbuch. Zustand: Neu. Neuware - 'In this encyclopedic biography, Nick Henck draws on almost everything ever published on Subcommander Marcos. The result is an analysis that first highlights Marcos's intellectual and political formation prior to his entering the Lacandon jungle in late 1983, and then illuminates the Subcommander's unique cultural and political flexibility, which ultimately served to let the EZLN be directed by the priorities of the indigenous communities of Chiapas. As Henck points out, this flexibility is what distinguished Marcos from other twentieth-century guerrilla leaders; it was pivotal in permitting the EZLN to play a central role in the democratization of Mexico after seventy years of one-party rule. This is a valuable reference book for all those interested in a detailed account of the rise of Subcommander Marcos and the EZLN in Chiapas.'--Lynn Stephen, author of 'Transborder Lives: Indigenous Oaxacans in Mexico, California, and Oregon'. Artikel-Nr. 9780822339953

Neu kaufen

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar