Inhaltsangabe

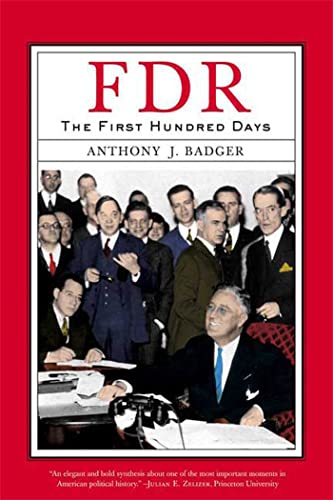

The Hundred Days, Franklin Roosevelt's first fifteen weeks in office, have become the stuff of legend, a mythic yardstick against which every subsequent American president has felt obliged to measure himself. The renowned historian Anthony J. Badger cuts through decades of politicized history to provide a succinct, balanced, and timely reminder that Roosevelt's accomplishment was above all else an exercise in exceptional political craftsmanship.

Roosevelt entered the White House in 1933 confronting 25 percent unemployment, bank closings, and a nationwide crisis in confidence. From March 9 to June 16, FDR secured sixteen major bills, many of which gave extraordinary discretionary power to the president. From legalizing the sale of beer to providing mortgage relief to millions of Americans, Roosevelt launched the New Deal that conservatives have been working to roll back ever since. Reintroducing the contingency that marked those fateful days, Badger humanizes Roosevelt and suggests a far more useful yardstick for future presidents: the politics of the possible under the guidance of principle.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Anthony J. Badger

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

FDR: The First Hundred Days

By Anthony J. BadgerHill and Wang

Copyright © 2009 Anthony J. BadgerAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780809015603

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für FDR: The First Hundred Days (Critical Issue)

FDR: The First Hundred Days (Critical Issue)

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Fair. First Edition. The item might be beaten up but readable. May contain markings or highlighting, as well as stains, bent corners, or any other major defect, but the text is not obscured in any way. Artikel-Nr. 0809015609-7-1-13

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

FDR: the First Hundred Days

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 7886914-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

FDR: the First Hundred Days

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 15101170-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 3 verfügbar

Fdr: The First Hundred Days

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0809015609I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Fdr: The First Hundred Days

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0809015609I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Fdr: The First Hundred Days

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0809015609I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Fdr: The First Hundred Days

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0809015609I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Fdr: The First Hundred Days

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0809015609I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Fdr: The First Hundred Days

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0809015609I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

FDR: The First Hundred Days (Critical Issue)

Anbieter: Roundabout Books, Greenfield, MA, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Clean, unmarked copy with some edge wear. Good binding. Dust jacket included if issued with one. We ship in recyclable American-made mailers. 100% money-back guarantee on all orders. Artikel-Nr. 1709236

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar