Verwandte Artikel zu Sun Yat-sen

Inhaltsangabe

Arguing that the life and work of Sun Yat-sen have been distorted by both myth and demythification, the author provides a fresh overall evaluation of the man and the events that turned an adventurer into the founder of the Chinese Republic and the leader of a great nationalist movement.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Charlotte y Peter Fiell son dos autoridades en historia, teoría y crítica del diseño y han escrito más de sesenta libros sobre la materia, muchos de los cuales se han convertido en éxitos de ventas. También han impartido conferencias y cursos como profesores invitados, han comisariado exposiciones y asesorado a fabricantes, museos, salas de subastas y grandes coleccionistas privados de todo el mundo. Los Fiell han escrito numerosos libros para TASCHEN, entre los que se incluyen 1000 Chairs, Diseño del siglo XX, El diseño industrial de la A a la Z, Scandinavian Design y Diseño del siglo XXI.

Von der hinteren Coverseite

This book argues that the life and work of Sun Yat-sen have been distorted both by the creation of the myth and by the attempts at demythification. Its aim is to provide a fresh overall evaluation of the man and the events that turned an adventurer into the founder of the Chinese Republic and the leader of a great nationalist movement. The Sun Yat-sen who emerges from this rigorously researched account is a muddled politician, an opportunist with generous but confused ideas, a theorist without great originality or intellectual rigor.

But the author demonstrates that the importance of Sun Yat-sen lies elsewhere. A Cantonese raised in Hawaii and Hong Kong, he was a product of maritime China, the China of the coastal provinces and overseas communities, open to foreign influences and acutely aware of the modern Western world (he was fund-raising in Denver when the eleventh attempt to bring down the Chinese empire finally succeeded). In facing the problems of change, of imitating the West, of rejecting or adapting tradition, he instinctively grasped the aspirations of his time, understood their force, and crystallized them into practical programs.

Sun Yat-sen’s gifts enabled him to foresee the danger that technology might represent to democracy, stressed the role of infrastructures (transport, energy) in economic modernization, and looked forward to a new style of diplomatic and international economic relations based upon cooperation that bypassed or absorbed old hostilities. These “utopias” of his, at which his contemporaries heartily jeered, now seem to be so many prophecies.

Aus dem Klappentext

This book argues that the life and work of Sun Yat-sen have been distorted both by the creation of the myth and by the attempts at demythification. Its aim is to provide a fresh overall evaluation of the man and the events that turned an adventurer into the founder of the Chinese Republic and the leader of a great nationalist movement. The Sun Yat-sen who emerges from this rigorously researched account is a muddled politician, an opportunist with generous but confused ideas, a theorist without great originality or intellectual rigor.

But the author demonstrates that the importance of Sun Yat-sen lies elsewhere. A Cantonese raised in Hawaii and Hong Kong, he was a product of maritime China, the China of the coastal provinces and overseas communities, open to foreign influences and acutely aware of the modern Western world (he was fund-raising in Denver when the eleventh attempt to bring down the Chinese empire finally succeeded). In facing the problems of change, of imitating the West, of rejecting or adapting tradition, he instinctively grasped the aspirations of his time, understood their force, and crystallized them into practical programs.

Sun Yat-sens gifts enabled him to foresee the danger that technology might represent to democracy, stressed the role of infrastructures (transport, energy) in economic modernization, and looked forward to a new style of diplomatic and international economic relations based upon cooperation that bypassed or absorbed old hostilities. These utopias of his, at which his contemporaries heartily jeered, now seem to be so many prophecies.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

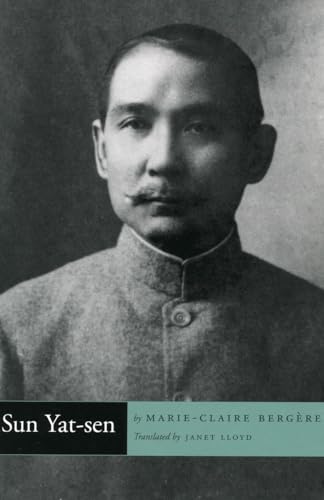

Sun Yat-sen

By MARIE-CLAIRE BERGÈRE, Janet LloydStanford University Press

All rights reserved.

Contents

| Note to Reader............................................................. | vii |

| Maps....................................................................... | ix |

| Introduction............................................................... | 1 |

| PART ONE The Adventurer of the Southern Seas, 1866–1905................... | 9 |

| 1. The Formative Years, 1866–1894.......................................... | 13 |

| 2. The Symbolic Creation of a Revolutionary Leader, 1894–1897.............. | 42 |

| 3. The Symbolic Creation of a Revolutionary Movement, 1897–1900............ | 69 |

| 4. The Awakening of Chinese Nationalism and the Founding of the Revolutionary Alliance, 1905............................................... | 97 |

| PART TWO The Founding Father? 1905–1920................................... | 137 |

| 5. Sun and the Revolutionary Alliance...................................... | 141 |

| 6. The Conspirator......................................................... | 173 |

| 7. The (Adoptive) Father of the Chinese Republic........................... | 198 |

| 8. Crossing the Desert, 1913–1920.......................................... | 246 |

| PART THREE Suns Last Years: National Revolution and Revolutionary Nationalism, 1920–1925..................................................... | 287 |

| 9. Sun Yat-sen, Soviet Advisers, and the Canton Revolutionary Base, 1920–1924.................................................................. | 293 |

| 10. Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People........................... | 352 |

| 11. Sun Yat-sen's Death and Transformation................................. | 395 |

| Biographical Sketches...................................................... | 423 |

| Notes...................................................................... | 437 |

| Bibliography............................................................... | 459 |

| Index...................................................................... | 471 |

| Photo section follows page 136............................................. |

CHAPTER 1

The Formative Years, 1866–1894

Sun Yat-sen was born into a very modest peasant family, raised in Hawaii byan elder brother with a flourishing shop, and educated in colleges in Hawaiiand Hong Kong. He was not an intellectual. He was no more attached to thetradition of the Chinese literati nurtured by years of study of the Classics, thanhe was to the Western culture of Hawaii and Hong Kong, neither of which, atthe end of the nineteenth century, represented that culture's finest flower. Butneither was he an ignoramus. Caught between two intellectual worlds, hetried to make his own way. He spoke English and wrote Chinese, and he hadread widely and had studied the rudiments of Western medicine. He derivedhis real education not from intellectual speculation but from the observationof the realities of his time.

China was at this time in a perilous state as a result of having been forciblyopened up to foreigners and also owing to the decline of the ruling dynasty.But in Chinas treaty ports a new society and a new culture were in the processof emerging: foreign trade was booming and there was a lively foreign presencethat stimulated a universal desire to get rich quickly; it was a triumph ofpragmatism. This coastal civilization, which included not only the mainlandcommunities but also those of the periphery (Hong Kong, Macao) and overseas,stood in contrast to the rural, bureaucratic, Confucian tradition of theprovinces of inland China. Canton, Hawaii, Hong Kong, and Macao, whereSun lived during his formative years, were among the major centers of thisnew civilization. Sun himself appears to have been a pure product of it.

The story of Sun's youth is thus not so much that of the schools he attended,the books he read, and the ideas that he mastered; rather, it is aboutthe encounters he had, the friendships he made, and the links that he established.Sun became part of a whole series of social circles that were to remainloyal to him throughout his career, starting, of course, with his family circleand the village and provincial communities of Guangdong, continuing withthe émigré community of Hawaii and the network of Chinese converts toChristianity and, through them, groups of missionaries, foreign protectors,and advisers, and leading as time passed to the Chinese elites of the treatyports, and even to the secret society lodges.

With consummate skill, Sun Yat-sen moved easily within this complex networkof contacts that sometimes overlapped, sometimes clashed. But always,however, his humble birth and unorthodox education prevented him frommoving into the world of the literati, the mandarins, and the gentry—still, fora man aspiring to a public role, the only world that counted in China.Perhaps the most humiliating snub occurred in 1894, when Sun was refusedadmittance by one of the most powerful imperial mandarins, Li Hongzhang(1823–1901), then governor-general of Zhili. Its effect upon this young Cantonesewas either to commit him to the path of opposition from the peripheryor to confirm him in that potentially novel and radical commitment.

CHINA IN CRISIS: THE ENFORCED OPENING-UP,DYNASTIC DECLINE, AND SOCIAL MALAISE

The Enforced Opening-up

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, the burgeoning capitalism of theWest increasingly forced China to open up its markets to world commerceand integrate its empire in the international order planned and organized bythe European powers. To better prevent conflicts and to preserve both peaceand the supremacy of the empire, these powers set about destroying thetraditional Chinese system that limited interaction among different peoples.With their immense technological progress in the fields of transport, armaments,and industrial production the Western powers could readily forceChina, however unwillingly, into the process of opening-up.

The process was initiated with the First Opium War in 1839 and it continuedduring the next six decades, culminating in the international expeditionto put down the Boxer rebellion in 1900–1901. There were many reasonswhy it took so long. The Western side was hampered not only by the limitedscale of the technology initially employed, the aim being not to conquerChina but to force it to trade with the European powers and recognize theirexistence, but also by the rivalry among the various powers. On the Chineseside, the opening-up process was slowed down both by the extreme coherenceof the traditional system and by its surprising flexibility, which for severaldecades enabled it to survive the fatal blow dealt it by the Opium Wars.

The treaties and conventions that brought the Opium Wars to an end (inNanking in 1842, Tianjin in 1858, and Peking in 1860–61) gave the foreigners acollection of rights and privileges that for nearly a century provided them witha legal framework for their penetration of China. A number of cities wereopened to them, where they acquired the right to reside, buy property, andengage in trade. Foreigners in these treaty ports benefited from the rights ofextraterritoriality and were liable only to the jurisdiction of their respectiveconsuls. The treaties also established free trade by canceling all forms ofofficial and monopolistic organization on the Chinese side and establishinguniform and moderate customs dues (5 percent ad valorem) on imports.Foreign goods were also granted dispensation from internal taxation {lijin) inreturn for the payment of a modest transit tax upon entering Chinese territory.Finally, the treaties allowed missionaries to pursue their religious andsocial activities, initially only in the treaty ports but subsequently throughoutthe country.

In practice, the privileges granted by the treaties were given ever broaderinterpretation. Thus, the concessions—originally simply zones of residencefor foreigners in the treaty ports—soon assumed the right of self-governmentand became veritable foreign enclaves. From the point of view of internationallaw, these privileges represented a grave infraction on the sovereignty of theChinese empire in that it was deprived of its jurisdiction over part of itsresident population and prevented from governing certain portions of itsterritory and establishing its own customs tariffs.

The Dynastic Decline

The progressive foreign penetration revealed the weakness of the imperialpower. It was embodied in a dynasty of Manchu origin, which the Chinesestill regarded as foreign despite its having been altogether swamped by theChinese culture. In the nineteenth century, this dynasty did not produce anygreat emperors of the caliber of those who had been the glory of China in thepreceding century. Following the splendid economic growth of the sixteenthto eighteenth centuries, stagnation had set in and from the 1820's on crisesmultiplied. Besides the deflation and the commercial contraction that affectedthe most developed regions of eastern and southern China, there was anincreasingly dangerous imbalance between population and agricultural production.In 1850 the population of China rose to 450 million, as a result of theexceptional demographic surge of the preceding centuries, while agriculturalproduction, following the settlement and colonization of the southern andwestern regions and in the absence of any technological revolution, seemedincapable of further development. Popular feeling reflected these difficulties,and with foreign intervention abetting, discontent eventually erupted in vastrebellions, the most serious of which, the Taiping movement, spread quicklythrough southern and eastern China between 1851 and 1864. The dynastyseemed on the point of collapsing. But it recovered, thanks mainly to theenergy and loyalty of a few Chinese high officials and military generals determinedto save the Confucian culture and political order; thanks also to helpfrom the Westerners, who preferred a stable, if weakened, power to uncontrollablerebels.

The stay of execution that history afforded the Manchus coincided withthe Tongzhi era (1862–75). In the cyclical concept of traditional Chinesehistory, this reign appears as a period of restoration (zhongxing) that temporarilyinterrupted the dynastic decline. The rulers of the Tongzhi era restoredorder and proceeded to rehabilitate the regions devastated and depopulatedby the rebellions and their repression. They did not, however, launch anyprogram of reform and modernization comparable to that of the Meiji periodof Japan.

The delay in confronting the Western challenge was to a large extentoccasioned by the delay in perceiving it. Although the Opium Wars hadforced China to open up to trade and diplomatic relations with the West, theyhad not shaken the mandarins' confidence in the superiority of the Confucianideology and the sociopolitical system that stemmed from it. The Westernerswere only one more species of barbarian, who, if they could not be repulsed,would simply have to be tolerated on the edges of the empire. They could beallowed both to manage their own affairs and to participate, with second-rankstatus, in the economic and administrative activities of the state and mightthereby even accede to civilization (by definition, Chinese). In short, themandarins in their ignorance of world affairs looked upon the system oftreaties, which the foreigners regarded as a "charter of privileges," as nothingmore than "a series of restrictive measures."

Nonetheless, some mandarins were anxious to know more about theWest—not that they conceded it the slightest intellectual or cultural superiority,but they could not help recognizing its military superiority. The progressof what might be called Chinese westernization was extremely slow. Aprogram for sending Chinese students to the United States, introduced in1870, was halted in 1875. The reports and memoranda written in the 1880'sand the early 1890's by the first Chinese diplomats in Europe testify to theignorance and bewilderment of these privileged observers. Public opinion—thatis to say the opinion of the literati and the imperial officials—remainedhostile to the opening-up and was critical of Sino-Western contacts. Effortsto adapt institutionally to the establishment of regular relations with theWest remained extremely limited. The Office for the General Administrationof Affairs concerning Various Countries (Zongli yamen), considered by theWesterners as a Ministry for Foreign Affairs, was in truth no more than asubsidiary and marginal cog in the Chinese administrative system.

A few important regional leaders, either viceroys or provincial governors,did draw more pertinent conclusions from these early contacts with the West,and from i860 on adopted modernization policies, known as the WesternAffairs Movement (Yangwu yundong). They were just as good Confucians asthe court mandarins and were equally convinced of the superiority of Chineseculture, but they recognized the weakness of the imperial armies and appreciatedthe efficiency of modern weaponry. Borrowing the technology of theWest would be a way of protecting the established order more successfully.

This first, essentially conservative Chinese attempt at modernization wascharacterized by a lack of coherence and continuity, which in part also explainedits failure. There was no organized plan for the setting up of arsenalsand construction sites, and a viceroy's transfer to another province or hisappointment to other duties was likely to jeopardize the development ofwhatever industries he had just established. The results of a whole decade ofefforts were disappointing. Under the influence of Li Hongzhang, the modernizationmovement did spread during the 1870's to the mining, steel, textile,and modern transport industries, following the sensible idea that China couldnot strengthen its military might (qiang) without at the same time developingits wealth (fu), that is to say without setting up the infrastructure indispensablefor a modern economic surge. In 1885, Chinas defeat in the Sino-Frenchwar, born from French colonial expansion in Tonking, revealed the meagernessof the results achieved by the renovated modernization program but didnot lead to any change in orientation or methods. Quite apart from theshortcomings of the strategy adopted, the causes of failure no doubt lay also inthe instrumental concept that guided this modernization effort, which couldbe summed by the famous Chinese saying: Western knowledge for the practicalapplication, Chinese learning for the essential principles (xixue weiyong,zhongxue wei ti). The leaders of the Western Affairs Movement sought toadopt foreign techniques without in any way changing the values of theChinese tradition.

This semicommitment to modernity was not of a kind to inspire anypolitics of real change, so in the end the Western Affairs Movement had littlereal impact on the Chinese economy and society. If anything, the movementprobably only strengthened the power of the major provincial governors, whocontrolled the embryo of modern production, and increased their autonomyin relation to the central government. So it was that even several decades afterbeing opened up, China had changed hardly at all. The trappings of powerhad been restored. After the death of the emperor Tongzhi,5 the governmentin Peking was dominated by the conservative Manchu princes in his entourageand, increasingly, by his mother, the dowager empress Cixi who, havingacted as regent in the name of her son, now, in the Guangxu period (1875–1908),ruled in the name of her nephew. The foreign presence remainedconfined to the south and east of the country, extending along the coast fromCanton to Shanghai, and it was essentially commercial in character. For theimperial bureaucracy, an illusion of grandeur still survived. More surprisingly,the power of China continued to inspire a certain respect on the part of thewitnesses and partial cause of its decline, the Westerners.

Social Malaise

In truth, society had by no means recovered its stability. Between i860 and1890, the general anxiety and malaise found expression in particular in a seriesof attacks upon missionaries. Though these were carried out by the xenophobicand superstitious masses and involved killing missionaries and lootingand destroying orphanages, they were encouraged by the gentry. Along withfeelings of racial humiliation and contempt for a doctrine that they consideredto be unorthodox and likely to undermine the established order, many inthe gentry, especially the local elites, felt that their prerogatives were beingthreatened by missionaries operating under the protection of the foreignpowers. The imperial power was helpless. It did not dare to place its trust ineither the popular xenophobia or the culturalist and patriotic reactions of thegentry. The policy of modernization to which it had been committed by ahandful of high-ranking mandarins forced it to cooperate, up to a point, withthe foreign powers, and besides, the uneven balance of military forces reallyleft it no choice. The main effect of the popular anti-Christian and anti-foreignercurrent was thus to swell the ranks of the secret societies, opposedboth to the established order and to the reigning dynasty. The local elitestended to organize themselves outside the bureaucratic framework and beyondits control, in order to protect their own interests and, increasingly, thoseof the country as a whole. But nowhere was the rift between the imperialauthority and society deeper than in the treaty ports.

The Emergence of a Coastal Civilization

The treaty system assured foreigners of a privileged position in the commercialdevelopment of the coastal regions. The modern sector then beginning totake shape in the ports resulted from foreign initiatives and remained largelyunder foreign control, but the Chinese merchants were widely associated withthis process. The large coastal cities, then in full expansion, offered themmany opportunities to grow rich. Those in the best position were the compradors,the intermediaries who made transactions between foreign firms andthe Chinese public possible. By the second half of the nineteenth century thecompradors had come to form a wealthy and highly respected group, in whichthe Cantonese played a dominant role. The cooperation between these merchantsand the foreigners generated a westernization process that was dictatedby the immediate circumstances. The compradors installed themselves inhouses built and furnished in the European style that were provided for themby their employers. As occasion demanded to serve their prestige and interests,they abandoned their long, blue, silk robes for jackets and trousers thatsymbolized their extraterritorial status. To communicate with their foreignpartners they used pidgin, a mixture of Anglo-Indian and Portuguese wordsset in Chinese constructions. A few converted to Christianity, though this wasusually so as to consolidate their positions in professional circles.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Sun Yat-sen by MARIE-CLAIRE BERGÈRE, Janet Lloyd. Copyright © 1994 Librairie Arthème Fayard, Paris. Excerpted by permission of Stanford University Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

- VerlagStanford University Press

- Erscheinungsdatum2000

- ISBN 10 0804740119

- ISBN 13 9780804740111

- EinbandTapa blanda

- SpracheEnglisch

- Anzahl der Seiten504

- Kontakt zum HerstellerNicht verfügbar

EUR 4,16 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenEUR 4,79 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. GOR010249826

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sun Yat-sen

Anbieter: PBShop.store UK, Fairford, GLOS, Vereinigtes Königreich

PAP. Zustand: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Artikel-Nr. FW-9780804740111

Anzahl: 15 verfügbar

Sun Yat-Sen

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Zustand: New. Arguing that the life and work of Sun Yat-sen have been distorted by both myth and demythification, the author provides a fresh overall evaluation of the man and the events that turned an adventurer into the founder of the Chinese Republic and the leader o. Artikel-Nr. 595014557

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Sun Yat-Sen

Anbieter: AHA-BUCH GmbH, Einbeck, Deutschland

Taschenbuch. Zustand: Neu. Neuware - Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925), the first president of the Republic of China, has left a supremely ambivalent political and intellectual legacy--so much so that he is claimed as a Founding Father by both the present rival governments in Taipei and Beijing. In Taiwan, he is the object of a veritable cult; in the People's Republic of China, he is paid homage as 'pioneer of the revolution,' making possible the Party's claims of continuity with the national past. Western scholars, on the other hand, have tended to question the myth of Sun Yat-sen by stressing the man's weaknesses, the thinker's incoherences, and the revolutionary leader's many failures.This book argues that the life and work of Sun Yat-sen have been distorted both by the creation of the myth and by the attempts at demythification. Its aim is to provide a fresh overall evaluation of the man and the events that turned an adventurer into the founder of the Chinese Republic and the leader of a great nationalist movement. The Sun Yat-sen who emerges from this rigorously researched account is a muddled politician, an opportunist with generous but confused ideas, a theorist without great originality or intellectual rigor.But the author demonstrates that the importance of Sun Yat-sen lies elsewhere. A Cantonese raised in Hawaii and Hong Kong, he was a product of maritime China, the China of the coastal provinces and overseas communities, open to foreign influences and acutely aware of the modern Western world (he was fund-raising in Denver when the eleventh attempt to bring down the Chinese empire finally succeeded). In facing the problems of change, of imitating the West, of rejecting or adapting tradition, he instinctively grasped the aspirations of his time, understood their force, and crystallized them into practical programs.Sun Yat-sen's gifts enabled him to foresee the danger that technology might represent to democracy, stressed the role of infrastructures (transport, energy) in economic modernization, and looked forward to a new style of diplomatic and international economic relations based upon cooperation that bypassed or absorbed old hostilities. These 'utopias' of his, at which his contemporaries heartily jeered, now seem to be so many prophecies. Artikel-Nr. 9780804740111

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sun Yat-sen

Anbieter: Ria Christie Collections, Uxbridge, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: New. In. Artikel-Nr. ria9780804740111_new

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar

Sun Yat-Sen

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. 1st edition. 492 pages. 9.50x6.25x1.25 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. x-0804740119

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar