Inhaltsangabe

For all their permeability, the borders snaking across the world have never been of greater importance. This is the dance of history in our age: slow, slow, quick, quick, slow, back and forth and from side to side, we step across these fixed and shifting lines. —from Part IV

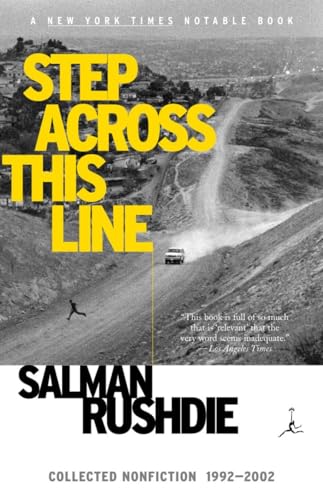

With astonishing range and depth, the essays, speeches, and opinion pieces assembled in this book chronicle a ten-year intellectual odyssey by one of the most important, creative, and respected minds of our time. Step Across This Line concentrates in one volume Salman Rushdie’s fierce intelligence, uncanny social commentary, and irrepressible wit—about soccer, The Wizard of Oz, and writing, about fighting the Iranian fatwa and turning with the millennium, and about September 11, 2001. Ending with the eponymous, never-before-published speeches, this collection is, in Rushdie’s words, a “wake-up call” about the way we live, and think, now.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Salman Rushdie is the author of fourteen previous novels, including Midnight’s Children (for which he won the Booker Prize and the Best of the Booker), Shame, The Satanic Verses, The Moor’s Last Sigh, and Quichotte, all of which have been shortlisted for the Booker Prize; a collection of stories, East, West; a memoir, Joseph Anton; a work of reportage, The Jaguar Smile; and three collections of essays, most recently Languages of Truth. His many awards include the Whitbread Prize for Best Novel, which he won twice; the PEN/Allen Foundation Literary Service Award; the National Arts Award; the French Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger; the European Union’s Aristeion Prize for Literature; the Budapest Grand Prize for Literature; and the Italian Premio Grinzane Cavour. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and he is a Distinguished Writer in Residence at New York University. He is a former president of PEN America. His books have been translated into over forty languages.

Von der hinteren Coverseite

For all their permeability, the borders snaking across the world have never been of greater importance. This is the dance of history in our age: slow, slow, quick, quick, slow, back and forth and from side to side, we step across these fixed and shifting lines. --from Part IV

With astonishing range and depth, the essays, speeches, and opinion pieces assembled in this book chronicle a ten-year intellectual odyssey by one of the most important, creative, and respected minds of our time. "Step Across This Line concentrates in one volume Salman Rushdie's fierce intelligence, uncanny social commentary, and irrepressible wit--about soccer, "The Wizard of Oz, and writing, about fighting the Iranian fatwa and turning with the millennium, and about September 11, 2001. Ending with the eponymous, never-before-published speeches, this collection is, in Rushdie's words, a "wake-up call" about the way we live, and think, now.

Aus dem Klappentext

For all their permeability, the borders snaking across the world have never been of greater importance. This is the dance of history in our age: slow, slow, quick, quick, slow, back and forth and from side to side, we step across these fixed and shifting lines. from Part IV

With astonishing range and depth, the essays, speeches, and opinion pieces assembled in this book chronicle a ten-year intellectual odyssey by one of the most important, creative, and respected minds of our time. Step Across This Line concentrates in one volume Salman Rushdie s fierce intelligence, uncanny social commentary, and irrepressible wit about soccer, The Wizard of Oz, and writing, about fighting the Iranian fatwa and turning with the millennium, and about September 11, 2001. Ending with the eponymous, never-before-published speeches, this collection is, in Rushdie s words, a wake-up call about the way we live, and think, now.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

From Part I: Essays

Out of Kansas

I wrote my first short story in Bombay at the age of ten. Its title was “Over the Rainbow.” It amounted to a dozen or so pages, was dutifully typed up by my father’s secretary on flimsy paper, and was eventually lost somewhere along my family’s mazy journeyings between India, England, and Pakistan. Shortly before my father’s death in 1987, he claimed to have found a copy moldering in an old file, but despite my pleadings he never produced it. I’ve often wondered about this incident. Maybe he never really found the story, in which case he had succumbed to the lure of fantasy, and this was the last of the many fairy tales he told me. Or else he did find it, and hugged it to himself as a talisman and a reminder of simpler times, thinking of it as his treasure, not mine—his pot of nostalgic, parental gold.

I don’t remember much about the story. It was about a ten-year-old Bombay boy who one day happens upon the beginning of a rainbow, a place as elusive as any pot-of-gold end zone, and as rich in promise. The rainbow is broad, as wide as the sidewalk, and constructed like a grand staircase. Naturally, the boy begins to climb. I have forgotten almost everything about his adventures, except for an encounter with a talking pianola whose personality is an improbable hybrid of Judy Garland, Elvis Presley, and the “playback singers” of the Hindi movies, many of which made The Wizard of Oz look like kitchen-sink realism.

My bad memory—what my mother would call a “forgettery”—is probably a blessing. Anyway, I remember what matters. I remember that The Wizard of Oz (the film, not the book, which I didn’t read as a child) was my very first literary influence. More than that: I remember that when the possibility of my going to school in England was mentioned, it felt as exciting as any voyage over rainbows. England felt as wonderful a prospect as Oz.

The wizard, however, was right there in Bombay. My father, Anis Ahmed Rushdie, was a magical parent of young children, but he was also prone to explosions, thunderous rages, bolts of emotional lightning, puffs of dragon smoke, and other menaces of the type also practiced by Oz, the great and terrible, the first Wizard Deluxe. And when the curtain fell away and we, his growing offspring, discovered (like Dorothy) the truth about adult humbug, it was easy for us to think, as she did, that our wizard must be a very bad man indeed. It took me half a lifetime to discover that the Great Oz’s apologia pro vita sua fitted my father equally well; that he too was a good man but a very bad wizard.

I have begun with these personal reminiscences because The Wizard of Oz is a film whose driving force is the inadequacy of adults, even of good adults. At its beginning, the weaknesses of grown-ups force a child to take control of her own destiny (and her dog’s). Thus, ironically, she begins the process of becoming a grown-up herself. The journey from Kansas to Oz is a rite of passage from a world in which Dorothy’s parent-substitutes, Auntie Em and Uncle Henry, are powerless to help her save her dog, Toto, from the marauding Miss Gulch, into a world where the people are her own size, and in which she is never treated as a child but always treated as a heroine. She gains this status by accident, it’s true, having played no part in her house’s decision to squash the Wicked Witch of the East; but by the end of her adventure she has certainly grown to fill those shoes—or, rather, those famous ruby slippers. “Who’d have thought a girl like you could destroy my beautiful wickedness?” laments the Wicked Witch of the West as she melts—an adult becoming smaller than, and giving way to, a child. As the Wicked Witch of the West “grows down,” so Dorothy is seen to have grown up. In my view, this is a much more satisfactory explanation for Dorothy’s newfound power over the ruby slippers than the sentimental reasons offered by the ineffably soppy Good Witch Glinda, and then by Dorothy herself, in a cloying ending that I find untrue to the film’s anarchic spirit. (More about this later.)

The helplessness of Auntie Em and Uncle Henry in the face of Miss Gulch’s desire to annihilate Toto the dog leads Dorothy to think, childishly, of running away from home—of escape. And that’s why, when the tornado hits, she isn’t with the others in the storm shelter, and as a result is whirled away to an escape beyond her wildest dreams. Later, however, when she is confronted by the weakness of the Wizard of Oz, she doesn’t run away but goes into battle—first against the Witch and then against the Wizard himself. The Wizard’s ineffectuality is one of the film’s many symmetries, rhyming with the feebleness of Dorothy’s folks; but the difference in the way Dorothy reacts is the point.

The ten-year-old boy who watched The Wizard of Oz in Bombay’s Metro cinema knew very little about foreign parts and even less about growing up. He did, however, know a great deal more about the cinema of the fantastic than any Western child of the same age. In the West, The Wizard of Oz was an oddball, an attempt to make a live-action version of a Disney cartoon feature despite the industry’s received wisdom (how times change!) that fantasy movies usually flopped. There’s little doubt that the excitement engendered by Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs accounts for MGM’s decision to give the full, all-stops-out treatment to a thirty-nine-year-old book. This was not, however, the first screen version. I haven’t seen the silent film of 1925, but its reputation is poor. It did, however, star Oliver Hardy as the Tin Man.

The Wizard of Oz never really made money until it became a television standard years after its original theatrical release, though it should be said in mitigation that coming out two weeks before the start of World War II can’t have helped its chances. In India, however, it fitted into what was then, and remains today, one of the mainstreams of “Bollywood” film production.

It’s easy to satirize the Indian commercial cinema industry. In James Ivory’s film Bombay Talkie, a journalist (the touching Jennifer Kendal, who died in 1984) visits a studio soundstage and watches an amazing dance number featuring scantily clad nautch girls prancing on the keys of a giant typewriter. The director explains that this is no less than the Typewriter of Life, and we are all dancing out “the story of our Fate” upon that mighty machine. “It’s very symbolic,” the journalist suggests. The director, simpering, replies: “Thank you.”

Typewriters of Life, sex goddesses in wet saris (the Indian equivalent of wet T-shirts), gods descending from the heavens to meddle in human affairs, magic potions, superheroes, demonic villains, and so on have always been the staple diet of the Indian filmgoer. Blond Glinda arriving in Munchkinland in her magic bubble might cause Dorothy to comment on the high speed and oddity of local transport operating in Oz, but to an Indian audience Glinda was arriving exactly as a god should arrive: ex machina, out of her divine machine. The Wicked Witch of the West’s orange puffs of smoke were equally appropriate to her super-bad status. But in spite of all the similarities, there are important differences between the Bombay cinema and a film like The Wizard of Oz. Good fairies and bad witches might superficially resemble the deities and demons of the Hindu pantheon, but in reality one of the most striking aspects of the worldview of The Wizard of Oz is its joy- ful and almost complete secularism. Religion is mentioned only once...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002...

Step Across This Line : Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 5088053-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679783490I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679783490I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679783490I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679783490I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679783490I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line

Anbieter: Majestic Books, Hounslow, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: New. pp. xi + 402. Artikel-Nr. 8069863

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. reprint edition. 402 pages. 8.25x5.25x0.75 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. 0679783490

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002 (Modern Library (Paperback))

Anbieter: Vulkaneifel Bücher, Birgel, Deutschland

Zustand: Wie neu. Auflage: Modern Library. 416 Seiten minimale Lagerspuren am Buch, Inhalt einwandfrei und ungelesen 226009 Sprache: Englisch Gewicht in Gramm: 320 13,1 x 2,3 x 20,2 cm, Taschenbuch. Artikel-Nr. 194117

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Zustand: New. Salman Rushdie is the author of fourteen previous novels, including Midnight&rsquos Children (for which he won the Booker Prize and the Best of the Booker), Shame, The Satanic Verses, The Moor&rsquos Last Sigh, and Quichotte, a. Artikel-Nr. 594878864

Neu kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar