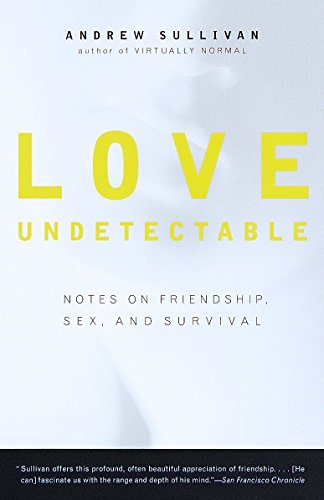

Verwandte Artikel zu Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Inhaltsangabe

"Sullivan offers [a] profound, often beautiful appreciation of friendship. . . . [He can] fascinate us with the range and depth of his mind."--San Francisco Chronicle

A New York Times Notable Book of the Year

"One of the great pleasures of this book lies in watching Sullivan's mind at work . . . [his essays] are filled with a passion and heat that most cultural criticism lacks." --Katie Roiphe, The Washington Post

When former New Republic editor Andrew Sullivan publicly revealed his HIV positive status in 1996, he intended "to be among the first generation that survives this disease." In this new book, a powerful meditation on the spiritual effect AIDS has on friendship, love, sexuality, and American culture, we follow Sullivan on his path to survival.

A practicing Catholic, Sullivan reflects on his faith in God, and expresses his bittersweet joy upon learning about new AIDS treatments that he believes led to the virus's recent transformation from a plague into a chronic illness. He revisits Freud to seek the origins of homosexuality and reviews the works of Aristotle, St. Augustine, and W. H. Auden to define friendship for a contemporary, post-plague world. Sullivan's last essay extols the virtues of friendship, elevating platonic love over the romantic, as he memorializes his best friend, who died of AIDS. Intensely personal and passionately political, Sullivan's essays are not just about his own experiences but also a powerful testament to human resilience, faith, hope, and love.

"Sullivan has found meaning in chaos. . . . With its paradoxical sense of beauty amid pain, Love Undetectable has something of the quality of a war memoir." --The New York Times Book Review

"On display here are all of the author's many strengths--compelling, poetic prose style, some keen observations on faith. . . . Sullivan offers a moving defense of the open gay male urban sexual culture and his participation in it." --The Boston Globe

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Andrew Sullivan lives in Washington, D.C.

Von der hinteren Coverseite

"Sullivan offers [a] profound, often beautiful appreciation of friendship. . . . [He can] fascinate us with the range and depth of his mind."--"San Francisco Chronicle

A "New York Times Notable Book of the Year

"One of the great pleasures of this book lies in watching Sullivan's mind at work . . . [his essays] are filled with a passion and heat that most cultural criticism lacks." --Katie Roiphe, "The Washington Post

When former New Republic editor Andrew Sullivan publicly revealed his HIV positive status in 1996, he intended "to be among the first generation that survives this disease." In this new book, a powerful meditation on the spiritual effect AIDS has on friendship, love, sexuality, and American culture, we follow Sullivan on his path to survival.

A practicing Catholic, Sullivan reflects on his faith in God, and expresses his bittersweet joy upon learning about new AIDS treatments that he believes led to the virus's recent transformation from a plague into a chronic illness. He revisits Freud to seek the origins of homosexuality and reviews the works of Aristotle, St. Augustine, and W. H. Auden to define friendship for a contemporary, post-plague world. Sullivan's last essay extols the virtues of friendship, elevating platonic love over the romantic, as he memorializes his best friend, who died of AIDS. Intensely personal and passionately political, Sullivan's essays are not just about his own experiences but also a powerful testament to human resilience, faith, hope, and love.

"Sullivan has found meaning in chaos. . . . With its paradoxical sense of beauty amid pain, Love Undetectable has something of the quality of a war memoir." --"The New York Times BookReview

"On display here are all of the author's many strengths--compelling, poetic prose style, some keen observations on faith. . . . Sullivan offers a moving defense of the open gay male urban sexual culture and his participation in it." --"The Boston Globe

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Love Undetectable

Notes on Friendship, Sex, and SurvivalBy Andrew SullivanVintage Books USA

Copyright © 1999 Andrew SullivanAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780679773153

Chapter One

1. WHEN PLAGUES END

The sense of what is real ... the thought if after all it should prove unreal...

--Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

FIRST, THE RESISTANCE to memory.

I arrived late at the hospital, fresh off the plane. It wasaround 8:30 and there was no light on in my friend Patrick'sapartment, so I went straight to the intensive careunit. When I arrived, my friend Chris's eyes were a reddenedblear of fright, the hospital mask slipped downunder his chin. I went into the room. When I first caughtsight of Pat, he was lying on his back, his body contortedso his neck twisted away and his arms splayed out, hishands palm upward, showing the intravenous tubes intohis wrists. Blood mingled with sweat in the creases of hisneck, his chest heaving up and down grotesquely withthe pumping of the respirator, a huge plastic tube forceddown his throat. His cold feet poked out from under thebedspread, as if separate from the rest of his body.

The week before, celebrating his thirty-first birthday inhis hometown on the Gulf Coast of Florida, we had swumtogether in the dark, warm space he had already decidedwould one day contain his ashes. It was clear that he hadknown something was about to happen. One afternoon onthe beach, he had gotten up to take a walk with his newlyacquired beagle, and had glanced back at me a secondbefore he left. All I can say is that, somehow, the glanceconveyed a complete sense of finality, the subtlest butclearest sign that it was, as far as he was concerned, over.Within three days, a massive fungal infection overtook hislungs, and at midnight, the vital signs began to plummet.

I remember walking slowly back to the intensive careroom when a sudden rush of people moved backwards outof the room. His brother motioned to the rest of us to run,and we sped toward him. Pat's heart had stopped beatingand after one attempt to restart it, we surrounded him andprayed: his mother and father and three brothers, hisboyfriend, ex-boyfriend and a handful of close friends.When the priest arrived, each of us received communion. Iremember I slumped back against the wall at the momentof his dying, reaching out for all the consolation I had beenused to reaching for--the knowledge that the worst wasyet to come, the memory of pain survived in the past--butsince it was happening now, and now had never felt sounavoidable, no relief was possible.

Perhaps this is why so many of us have found it hardto accept that this ordeal may be over. Because it meanswe may now be required to relent from our clenchingagainst the future and remember the past.

IF I COULD PINPOINT a moment when the reality sunkin for me, it was a summer evening in 1996. I was atthe July 30 meeting of something called the Treatment ActionGroup, an AIDS activist organization, in Manhattan.In its heyday, in the early 1990s, this group had livedand breathed a hard-edged skepticism. They were, afterall, the no-nonsense successors to the AIDS action group,ACT UP. But as soon as I arrived--for a meeting to discussthe data presented at a recent AIDS conference--I couldsense something had changed. Even at eight o'clock, therewas a big crowd--much larger, one of the organizers toldme, than the regular meetings. In the middle sat DavidHo, a pioneering AIDS researcher, and Marty Markowitz,the doctor who had presided over some of the earliestclinical trials of the new "combination therapy" for HIVinfection. As the crowd stared at them and they starednervously back, the two scientists interspersed their whispersto one another with the occasional, gleeful smile.

The meeting began with a blur of data. Ho and Markowitzdetailed again what had already hit the headlines:how, in some trials of patients taking the new proteaseinhibitors used in combination with older AIDS drugs, theamount of virus in the bloodstream had been reducedon average by between a hundred- and a thousand-fold.Within a few weeks of treatment with the new drugs, theyelaborated, levels of up to six million viral particles in amilliliter of a patient's blood had been reduced to belowfour hundred in most cases. That is, no virus could befound on the most sophisticated tests available. And, sofar, the results had lasted.

When Ho finished speaking, there was, at first, anumbed silence. And then the questions followed, likefirecrackers of denial. How long did it take for the virusto clear from the bloodstream? What about the virus stillhiding in the brain or the testes? What could be done forthe people who weren't responding to the new drugs? Wasthere resistance to the new therapy? Could a new, evenmore lethal viral strain be leaking out into the population?The answers that came from Ho and Markowitz were justas insistent. No, this was not a "cure." But the disappearanceof the virus in the bloodstream was beyond the expectationsof even the most optimistic of researchers. It waslikely that there would be some impact on the virus--althoughless profound--in the brain or testes, and newdrugs were able to reach those areas better. And since theimpact of the drugs was so powerful, it was hard for resistanceto develop because resistance is what happens whenthe virus mutates in the presence of the drugs--and therewas no virus detectable in the presence of the drugs.

The crowd palpably adjusted itself; and a few rusty officechairs squeaked. These were the hard-core skeptics, Iremember thinking to myself, and even they couldn't disguisewhat was going through their minds. There werecaveats, of course. The latest drugs were very new, andlarge studies had yet to be done. There was already clinicalevidence that a small minority of patients, especiallythose in late-stage disease, were not responding as wellto the new drugs and were experiencing a "breakout" ofthe virus after a few weeks or months. Although somepeople's immune systems seemed to recover, others'seemed damaged for good. The long-term toxicity of thedrugs themselves--their impact on the liver and heart, forexample--could mean that patients might stage a miraculousrecovery at the start, only to die from the effects oftreatment in later life. And the drugs themselves wereoften debilitating. After testing positive in 1993, I had beenon combination therapy ever since. When I added the proteaseinhibitors in March of 1996, the nausea, diarrhea,and constant fatigue had been overwhelming.

But I remember that meeting all too vividly now, and thesimple, unavoidable future it presaged. The next day, in afriend's apartment, I spoke the words I never believed Iwould speak in my lifetime. "It's over," I said. "Believe me.It's over."

MOST OFFICIAL STATEMENTS about the disease, of course--thestatements by responsible scientists, by AIDS activistorganizations, by doctors--do not concede that theplague is at an end. And, in one vital sense, obviously it'snot. In the time it takes you to read this sentence, someonesomewhere will be infected with HIV. Worldwide, thenumbers affected jump daily--some 30 million humanbeings at the latest estimate. Almost all of these people--anda real minority in America--will not be able to haveaccess to the treatments now available. And many, manyof these people will still die. Nothing I am saying here ismeant to deny that fact, or to mitigate its awfulness. I amnot saying here (nor would I ever say) that some lives areworth more than others, or that some lives are worth moreattention than others. To speak of the experience of someis not to deny the experience of others or to deny its importance.But it is not illegitimate to speak of what you know,while conceding a large part of what you do not know. Andthere is a speciousness to the idea that what is true is somehowuntrue because it isn't everything.

So I do not apologize for the following sentence. It istrue--and truer now than it was when it was first spoken,and truer now than even six months ago--that somethingprofound in the history of AIDS has occurred these lasttwo years. The power of the new treatments and the evengreater power of those now in the pipeline are such that adiagnosis of HIV infection in the West is not just differentin degree today than, say, in 1994. For those who can getmedical care, the diagnosis is quite different in kind. It nolonger signifies death. It merely signifies illness.

This is a shift as immense as it is difficult to grasp. So letme make what I think is more than a semantic point: aplague is not the same thing as a disease. It is possible,for example, for a plague to end, while a disease continues.A plague is something that cannot be controlled, somethingwith a capacity to spread exponentially out of its borders,something that kills and devastates with democraticimpunity, something that robs human beings of the abilityto respond in any practical way. Disease, in contrast, is generallydiagnosable and treatable, with varying degrees ofsuccess; it occurs at a steady or predictable rate; it countsits progress through the human population one person,and often centuries, at a time. Plague, on the other hand,cannot be cured, and it never affects one person. It affectsmany, and at once, and swiftly. And by its very communalnature, by its unpredictability and by its devastation,plague asks questions disease often doesn't. Disease isexperienced; plague is spread. Disease is always with us;plagues come and go. And some time toward the end of themillennium in America, the plague of AIDS went.

You could see it in the papers. Almost overnight, towardthe end of 1996, the obituary pages in the gay press beganto dwindle. Soon after, the official statistics followed.Within a year, AIDS deaths had plummeted 60 percent inCalifornia, 44 percent across the country as a whole. Intime, it was shown that triple combination therapy inpatients who had never taken drugs before kept close to90 percent of them at undetectable levels of virus for twofull years. Optimism about actually ridding the body completelyof virus dissipated; what had at one point beenconceivable after two years stretched to three and thenlonger. But even for those who had developed resistanceto one or more drugs, the future seemed tangibly brighter.New, more powerful treatments were fast coming on-stream,month after month. What had once been a handfulof treatment options grew to over twenty. In trials, thenext generation of AZT packed a punch ten times as powerfulas its original; and new, more focused forms of proteaseinhibitor carried with them even greater promise.It was still taboo, of course, to mention this hope--forfear it might encourage a return to unsafe sex and a newoutburst of promiscuity. But, after a while, the numbersbegan to speak for themselves.

It remains true, however, that anyone who even understoodthe minimal amount of the science could havepredicted these figures as early as 1995. By that steamysummer night in 1996, the implications were unavoidable,and you could sense it in the air. After the meeting, as wespilled out into the street, a slightly heady feeling waftedover the crowd. A few groups headed off for a late dinner,others to take their protease drugs quickly on an emptystomach, others still to bed. It was after ten o'clock, and Iremember wandering aimlessly into a nearby bar, wherelate-evening men in suits gazed up at muscle-boy videos,their tired faces and occasional cruising glances a weirdlycomforting return to normality. But as I checked my notebookat the door and returned to the bar to order a drink,the phrase a longtime AIDS activist had spoken to me earlierthat day began to reverberate in my mind. He'd beentalking about the sense of purpose and destiny he hadonce felt as part of his diagnosis. "It must be hard to findout you're positive now," he had said, darkly. "It's like youreally missed the party."

AT SIX O'CLOCK in the morning in Manhattan's RoselandBallroom, the crowds were still thick. I'd arrived fourhours earlier, after a failed attempt to sleep beforehand. Achaotic throng of men crammed the downstairs lobby,attempting to check coats. There were no lines as such,merely a subterranean, almost stationary mosh pit, stiflinglyhot, full of inflated muscular bodies, glacially driftingtoward the coat-check windows. This was, for some,the high point of the year's gay male social calendar. It'scalled the Black Party, one of a series of theme partiesheld year-round by a large, informal group of affluent,mainly white, gay men and several thousand admirers.It's part of what's been dubbed the "circuit," a series ofvast, drug-enhanced dance parties held in various citiesacross the country, and now a resilient, if marginal, featureof an emergent post-AIDS gay urban "lifestyle."

Until the late 1990s, almost nothing had been written inthe mainstream media about these parties, except whenthey had jutted their way into controversy. A new circuitparty, called "Cherry Jubilee," in Washington, D.C.,incurred the wrath of Congressman Robert Dornan for toleratingdrug use in a federal building leased for the event.The annual Morning Party in August in Fire Island, held toraise money for Gay Men's Health Crisis in New York, wascriticized on similar grounds by many in the gay worlditself. But slowly, the proliferation of these events (theynumbered at least two a month in cities as diverse asMiami and Pittsburgh) became impossible to ignore, andthe secrecy that once shrouded them turned into an increasinglyraucous debate on the front pages of newspapersacross the country. Despite representing a tinysub-subculture and dwarfed, for example, by the explosionof gay religion and spirituality in the same period,the parties seemed to symbolize something larger: thequestion of whether, as AIDS receded, gay men were preparedto choose further integration, or were poised toleap into another spasm of libidinal pathology.

The Black Party, like all such events, was made possibleby a variety of chemicals: steroids, which began as therapyfor wasting men with AIDS, and became a means to perpetuatestill further the cult of bodybuilding; and psychotherapeuticdesigner drugs, primarily Ecstasy, ketamine(or "Special K"), and "crystal meth." The whole place, withoutthis knowledge, could be taken for a mass of menin superb shape, merely enjoying an opportunity to letoff steam. But underneath, there was an air of strain, ofsexual danger translated into sexual objectification, theunspoken withering of the human body transformed intoa reassuring inflation of muscular body mass.

I had never known these events in their heyday, in thelate 1970s and early 1980s. Begun in a legendary discoin Manhattan, the Saint, they had mesmerized an entiregeneration of homosexual urbanites. I was taken to onein the mid-1980s, as the plague had begun to descend, buteven then, its effects were hard to determine. What yousaw was an oasis of astonishing masculine beauty, of akind our society never self-consciously displays in theopen. I remember feeling at first a gasp of disbelief, asense that, finally, I was surrounded by visions that hadonce only existed in my head. These people were notboys, they were men. And they were not merely men,they were men in the deepest visible sense of that word,men whose muscular power flickered in the shadows,men whose close sweat and buzzed hair and predatoryposturing intimated almost a parody of the masculine,men whose self-conscious sexuality set them apart fromthe heterosexual world--and indeed from the homosexualworld outside the hallowed precepts of this space.What would the guardians of reality think, I rememberasking myself, if they could see this now, see this displayof unapologetic masculinity, and understand that it washomosexual?

The critics of these events have predictably lambastedthis glorification of the masculine. They have seen in it anecho of the gender oppression directed by straight menagainst gay men and lesbians and heterosexual women, anappropriation by homosexuals of the very male supremacythat stigmatizes and marginalizes them. And indeed,in the darkness of that night there was an unmistakablyDarwinian element to the whole exercise. While the slimand effeminate hovered at the margins, the center of thedance floor and the stage areas were dedicated to the mostmale archetypes, their muscles and arrogance like a magnetof self-contempt for the rest. But at the same time, itwas hard also not to be struck, as I was the first time I sawit, by a genuine, brazen act of cultural defiance, a spectacledesigned not only to exclude but to reclaim a gender, theultimate response to a heterosexual order that denies gaymen the masculinity that is also their own.

And much of it was not merely playacting. To be sure,if you looked around, you saw an efflorescence of masculinesymbolism that was as strained as it was crude.Thick torsos, bull necks, and ribbed abdominals weredraped with the paraphernalia of the archetype: leather,sports clothes, sneakers, tank tops, tattoos. But behind it,a more convincing affect: beyond the dancing and socializing,a kind of circling, silent interaction, a drifting,almost menacing, courtship of male brevity and concision.It was raw male sexuality distilled, of a kind that unitesstraight and gay men and separates them from women:without emotion, without knowledge, without apparentweakness, armored with testosterone and an almostmarblelike hardness of touch.

There was a numbness to it, as well. The first few timesI went to these events, I made an elementary mistake oftrying to engage my fellow partiers, of trying to catchtheir eyes or strike up conversation. But they were anesthetized,almost as if this display was only possible bydistancing themselves from their mental being, pushingthemselves into a drug-induced distance from their mindsand others', turning their bodies into images in a cataloguewhose pages they turned, in a bored, fitful trance.And as the night stretched into morning, and as the drugsreached their peak in the bloodstream of these masses,the escape became more complete, the otherness moreperfect, the paradox of reclaiming their selves more intenseas the outside world got up, made coffee, and busieditself about the day. I remember once leaving one ofthese parties at 11:30 in the morning, a dark, cavernousblur of flesh and body still imprinted on my mind when,in an instant, we were thrust out onto the streets of Manhattan,unthinking strangers walking briskly past in thebright whiteness of a cloudy morning. None of this, I felt,cared for us; none of it even knew of us. Which was both athoroughly depressing and energizing thought.

What these events really were not about, whatevertheir critics have claimed, was sex. And as circuit partiesintensified in frequency and numbers in the 1990s, thisbecame more, not less, the case. When people feared thatthe ebbing of AIDS would lead to a new burst of promiscuity,to a return to the 1970s in some mindless celebrationof old times, they were, it turns out, only half right. Althoughsome bathhouses revived, their centrality to gaylife all but disappeared. What replaced sex was the ideaof sex; and what replaced promiscuity was the idea ofpromiscuity, masked, in the burgeoning numbers of circuitparties around the country, by the ecstatic high ofdrug-enhanced dance music. These were not merely masscelebrations on the dawn of a new era; they were ravesbuilt upon the need for amnesia.

They were, of course, built on drugs. And the kind ofdrugs was as revealing as the fact of them: Ecstasy, a substancethat instantly simulated an intimacy so many menfound almost impossible to achieve, and an exhilarationthey could not otherwise allow themselves to feel; ketamine,a powder that tipped them into an oblivion a partof them inwardly craved; crystal meth, a substance thatgave them an endurance and power they hadn't yet beenable to attain for real; and anabolic steroids--literally,injected masculinity--providing an illusion of male self-confidencewhere far too little of it existed for real. Thesedrugs are illusions--pathetic, debilitating--and also tellingillusions. They are rightly seen as the antithesis of thenew era of responsibility and maturity the end of AIDSactually promised. But they are also, perhaps, merely thecheapest version of such an era, lasting hours, not decades,and bought with money, not life.

In the circuit parties you see perhaps the double-edgednature of a segment of gay male sexuality as clearly asanywhere else: the physical shallowness and emotionalcowardice, the cult of youth, and the longing for masculinity;but also the desperate need for belonging, forsupport and reassurance, above all for intimacy, for aworld which can offer gay men, if only they could seize it,the chance for the emotional reality which this spectacleof alienation merely intimated and postponed.

As the early morning stretched on, my friends and Istood in the recess of a back bar as the parade of bodiespassed relentlessly by. Some of them glided past, intent onsome imminent conquest; others stumbled toward me,eyes glazed, bodies stooped in a kind of morbid stupor,staring at the floor or into space; others still stood in corners,chatting, socializing, their arms draped around eachother, a banal familiarity belying the truly bizarre scenearound them. Beyond, a mass of men danced the earlymorning through, strobe lights occasionally glinting offthe assorted deltoids, traps, lats, and other muscle groups.At the party's peak--around 7 a.m.--there must have beenaround six thousand men in the room, some parading on adistant stage, others locked in a cluster of rotating pectoralmuscles, embracing each other in a drug-inducedemotional high. And then the habitual climax, the soundof the Black Party's signature song, "Left to My Own Devices,"a gay elegy of longing and detachment, descendedon the scene:

I could leave you,

Say Goodbye.

I could love you,

If I tried.

And I could.

And left to my own devices, I probably would.

And as the music pounded, and the men swarmedcloser together, and the posture of maleness and intimacymelded into one hazy blur of movement, I foundmyself moving quietly away. For a group of men who hadjust witnessed a scale of loss normally visited only uponwar generations, it was a curious spectacle. For some, I'msure, the drugs helped release emotions they could hardlyaddress alone or sober; for others, the ritual was a way ofdefying their own infections, their sense of fragility orguilt at survival. For others still, including myself, it was aconflicting puzzle of impulses. The need to find some solidarityamong the loss, to assert some crazed physicalityagainst the threat of sickness, to release some of the toxinsbuilt up over a decade of constant stress. Beyondeverything, the desire to banish the memories that willnot be banished, to shuck off--if only till the morning--thematurity that plague had brutally imposed.

But even so, I couldn't be among them. It was too muchto experience--at least, not together.

[CHAPTER ONE CONTINUES ...]

Continues...

Excerpted from Love Undetectableby Andrew Sullivan Copyright © 1999 by Andrew Sullivan. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

EUR 3,52 für den Versand von USA nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenEUR 11,49 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Artikel-Nr. G0679773150I3N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Artikel-Nr. G0679773150I3N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Artikel-Nr. G0679773150I4N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Artikel-Nr. G0679773150I3N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Artikel-Nr. G0679773150I4N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable

Anbieter: Hamelyn, Madrid, M, Spanien

Zustand: Bueno. : Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival es un libro de Andrew Sullivan publicado en 1999. En esta obra, Sullivan reflexiona sobre el impacto espiritual del SIDA en la amistad, el amor, la sexualidad y la cultura estadounidense. El autor, que reveló públicamente su estado seropositivo en 1996, comparte sus experiencias y reflexiones sobre la fe, los tratamientos médicos y la evolución de la enfermedad. A través de ensayos personales y políticos, Sullivan ofrece un testimonio de resiliencia, esperanza y amor en un mundo afectado por el SIDA. EAN: 9780679773153 Tipo: Libros Categoría: Salud y Bienestar Título: Love Undetectable Autor: Andrew Sullivan Editorial: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group Idioma: en Páginas: 272 Formato: tapa blanda. Artikel-Nr. Happ-2025-04-30-d82482be

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Artikel-Nr. 0679773150-11-1

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable : Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 4597015-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable : Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 734549-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Love Undetectable : Notes on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 4597015-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar