Inhaltsangabe

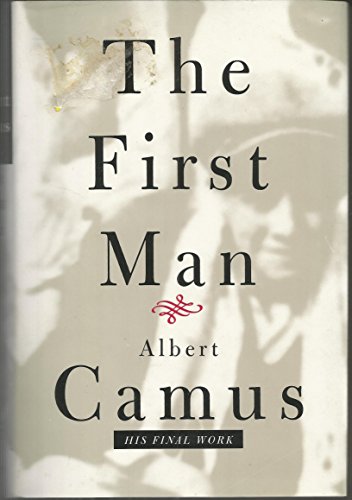

Based on the unfinished manuscript that he was working on at the time of his death, an epic based on Camus's childhood in Algeria profiles a poverty-stricken and fatherless boy who manages to find the small joys of life. 25,000 first printing.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Born in Algeria in 1913, Albert Camus published The Stranger-- now one of the most widely read novels of this century-- in 1942. Celebrated in intellectual circles, Camus was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. On January 4, 1960, he was killed in a car accident.

Aus dem Klappentext

Man Albert Camus tells the story of Jacques Cormery, a boy who lived a life much like his own. Camus summons up the sights, sounds, and textures of a childhood circumscribed by poverty and a father's death yet redeemed by the austere beauty of Algeria and the boy's attachment to his nearly deaf-mute mother. The result is a moving journey through the lost landscape of youth that also discloses the wellspring of Camus' aesthetic powers and moral vision.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Intercessor: Widow Camus

To you who will never be able to read this book

Above the wagon rolling along a stony road, big thick clouds were hurrying to the East through the dusk. Three days ago they had inflated over the Atlantic, had waited for a wind from the West, had set out, slowly at first then faster and faster, had flown over the phosphorescent autumn waters, straight to the continent, had unraveled on the Moroccan peaks, had gathered again in flocks on the high plateaus of Algeria, and now, at the approaches to the Tunisian frontier, were trying to reach the Tyrrhenian Sea to lose themselves in it. After a journey of thousands of kilometers over what seemed to be an immense island, shielded by the moving waters to the North and to the South by the congealed waves of the sands, passing scarcely any faster above this nameless country than had empires and peoples over the millennia, their momentum was wearing out and some already were melting into occasional large raindrops that were beginning to plop on the canvas hood above the four travelers.

The wagon was creaking over a route that was fairly well marked but had scarcely any surfacing. From time to time a spark would flash under a metal wheel rim or a horse's hoof, and a stone would strike the wood of the wagon or else would sink with a muted sound into the soft soil of the ditch. Meanwhile the two small horses moved steadily ahead, occasionally flinching a bit, their chests thrust forward to pull the heavy wagon, loaded with furniture, continuously putting the road behind them as they trotted along at different paces. One of them would now and then blow the air noisily from its nostrils, and would be thrown off its pace. Then the Arab who was driving would snap the worn reins flat on its back, and the beast would gamely pick up its rhythm.

The man who was on the front seat by the driver, a Frenchman about thirty, gazed with an impenetrable look at the two rumps moving rhythmically in front of him. He was of medium height, stocky, with a long face, a high square forehead, a strong jaw, and blue eyes. Though the season was well along, he wore a three-button duckcloth jacket, fastened at the neck in the style of that time, and a light pith helmet over his close-cut hair. When the rain began streaming across the canvas above them, he turned toward the inside of the vehicle: "Are you all right?" he shouted.

On a second seat, wedged between the first seat and a heap of old trunks and furniture, sat a woman who, though shabbily dressed, was wrapped in a coarse woolen shawl. She smiled feebly at him. "Yes, yes," she said, with a little gesture of apology. A small four-year-old boy slept leaning against her. She had a gentle look and regular features, a warm gaze in her brown eyes, a small straight nose, and the black wavy hair of a Spanish woman. But there was something striking about that face. Not only would fatigue or something similar momentarily mask its features; no, it was more like a faraway look, a look of sweet distraction, such as you always see on some simpletons, but which would burst out only fleetingly on the beauty of this face. The kindness of that gaze, which was so noticeable, would sometimes be joined by a gleam of unreasoning fear that would as instantly vanish. With the flat of her hand, already worn with work and somewhat gnarled at the joints, she tapped her husband's back: "It's all right, it's all right," she said. And immediately she stopped smiling to watch, from under the canvas top, the road where puddles were already beginning to shine.

The man turned to the Arab, placid in his turban with its yellow cords, his body made stouter by baggy pants with a roomy seat gathered above the calf. "Do we have much farther to go?"

The Arab smiled under his big white moustache. "Eight kilometers and you're there."

The man turned to look at his wife, not smiling yet attentive. She had kept her eyes on the road. "Give me the reins," the man said.

"As you wish,"said the Arab. He handed him the reins, and the man stepped across while the old Arab slipped under him to the place just vacated. With two slaps of the flat of the reins the man took over the horses, who picked up their trot and suddenly were pulling straighter. "You know horses," the Arab said.

The husband's reply was curt and unsmiling. "Yes," he said.

The light had dimmed and all at once night settled in. The Arab took the square lantern from its catch at his left and, turning toward the back, used several crude matches to light the candle inside it. Then he replaced the lantern. Now the rain was falling gently and steadily. It shone in the weak light of the lamp, and, all around, it peopled the utter darkness with its soft sound. Now and then the wagon skirted spiny bushes; small trees were faintly lit for a few seconds. But the rest of the time it rolled through an empty space made still more vast by the dark of night. The smell of burned grass, or, suddenly, the strong odor of manure, was all that suggested they were passing by land under cultivation. The wife spoke behind the driver, who held his horses in a bit and leaned back. "There are no people here," the wife said again.

"Are you afraid?"

"What?"

The husband repeated the question, but this time he was shouting.

"No, no, not with you." But she seemed worried.

"You're in pain," the man said.

"A little."

He urged his horses on, and once more all that filled the night were the heavy sounds of the wheels crushing ridges in the road and the eight shod hooves striking its surface.

It was a night in the fall of 1913. Two hours earlier the voyagers had left the railroad station in B?ne where they had arrived from Algiers after a journey of a night and a day on hard third-class benches. In the station they had found the wagon and the Arab waiting to take them to the farm located near a small village, about twenty kilometers into the interior of the country, where the husband was to take over the management. It had taken time to load the trunks and their few belongings, and then the bad road had delayed them still further. The Arab, as if aware of his companion's disquiet, said to him: "Have no fear. Here there are no bandits."

"They're everywhere," the man said. "But I have the necessary." And he slapped his tight pocket.

"You're right," said the Arab. "There's always madmen."

At that moment, the woman called her husband. "Henri," she said. "It hurts."

The man swore and pushed his horses a bit more. "We're getting there," he said. After a moment, he looked at his wife again. "Does it still hurt?"

She smiled at him with a strangely absent air, yet she did not seem to be suffering."Yes, a lot."

He continued to gaze gravely at her.

Again she apologized. "It's nothing. Maybe it's the train."

"Look," the Arab said, "the village." Indeed they could see, to the left of the road and a little farther on, the lights of Solf?rino blurred by the rain. "But you take the road to the right,"said the Arab.

The man hesitated, then turned to his wife. "Should we go to the house or the village?" he asked.

"Oh, to the house, that's better."

A bit farther, the vehicle turned to the right toward the unfamiliar house that awaited them. "Another kilometer," said the Arab.

"We're getting there," the man said, in the direction of his wife. She was bent over double, her face in her arms. "Lucie," the man said. She did not move. The man touched her...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für The First Man

The First Man

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. L06F-00808

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I4N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I4N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I4N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Fair. No Jacket. Former library book; Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I5N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I3N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The First Man

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679439374I4N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar