Inhaltsangabe

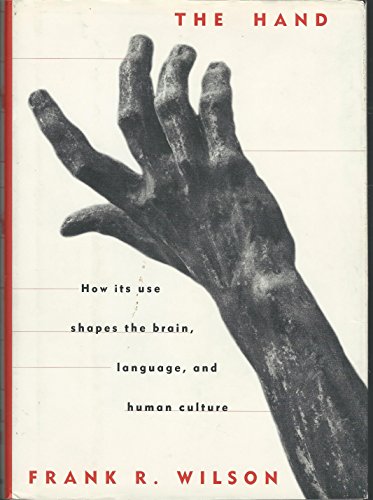

Drawing from anthropology, physiology, and neurology, and using the examples of jugglers, surgeons, musicians, and puppetmakers, the author explores the role of the hand in how humans learn and form their identities. 20,000 first printing.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorinnen und Autoren

Frank R. Wilson is a neurologist and the medical director of the Peter F. Ostwald Health Program for Performing Artists at the University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco. He is a graduate of Columbia College in New York City and of the University of California School of Medicine in San Francisco. The author of Tone Deaf and All Thumbs?, he lives with his wife, Patricia, in Danville, California. He can be reached by e-mail at handoc@well.com.

Frank R. Wilson is a neurologist and the medical director of the Peter F. Ostwald Health Program for Performing Artists at the University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco.

Aus dem Klappentext

man hand is so beautifully formed, its actions are so powerful, so free and yet so delicate that there is no thought of its complexity as an instrument; we use it as we draw our breath, unconsciously." With these words written in 1833, Sir Charles Bell expressed the central theme of some of the most far-reaching and exciting research being done in science today. For humans, the lifelong apprenticeship with the hand begins at birth. We are guided by our hands, and we are indelibly shaped by the knowledge that comes to us through our use of them.

The Hand delineates the ways in which our hands have shaped our development--cognitive, emotional, linguistic, and psychological--in light of the most recent research being done in anthropology, neuroscience, linguistics, and psychology. How did structural changes in the hand prepare human ancestors for increased use of tools and for our own remarkable ability to design and manufacture them? Is human language rooted in speech, or

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Prologue

Early this morning, even before you were out of bed, your hands and arms came to life, goading your weak and helpless body into the new day. Perhaps your day began with a lunge at the snooze bar on the bedside radio, or a roundhouse swing at the alarm clock. As the shock of coming awake subsided, you probably flapped the numb, tingling arm you had been sleeping on, scratched yourself, and maybe even rubbed or hugged someone next to you.

After tugging at the covers and sheets and rolling yourself into a more comfortable position, you realized that you really did have to get out of bed. Next came the whole circus routine of noisy bathroom antics: the twisting of faucet handles, opening and closing of cabinet and shower doors, putting the toilet seat back where it belongs. There were slippery things to play with: soap, brushes, tubes, and little jars with caps and lids to twist or flip open. If you shaved, there was a razor to steer around the nose and over the chin; if you put on makeup, there were pencils, brushes, and tubes to bring color to eyelids, cheeks, and lips.

Each morning begins with a ritual dash through our own private obstacle course--objects to be opened or closed, lifted or pushed, twisted or turned, pulled, twiddled, or tied, and some sort of breakfast to be peeled or unwrapped, toasted, brewed, boiled, or fried. The hands move so ably over this terrain that we think nothing of the accomplishment. Whatever your own particular early-morning routine happens to be, it is nothing short of a virtuoso display of highly choreographed manual skill.

Where would we be without our hands? Our lives are so full of commonplace experience in which the hands are so skillfully and silently involved that we rarely consider how dependent upon them we actually are. We notice our hands when we are washing them, when our fingernails need to be trimmed, or when little brown spots and wrinkles crop up and begin to annoy us. We also pay attention to a hand that hurts or has been injured.

The book you are holding is a meditation on the human hand, born of nearly two decades of personal and professional experiences that caused me to want to know more about the hand. Among these, two had the greatest impact: first, as an adult musical novice, I tried to learn how to play the piano; second, as an experienced neurologist, I began to see patients who were having difficulty using their hands. Each experience afforded its own indelible lessons; each spawned its own progeny of questions.

Like most people, I have spent the better part of my life oblivious to the workings of my own hands. My first extended attempt to master a specific manual skill for its own sake took place at the piano. I was in my early forties at the time and in my dual role as parent and neurologist had become enchanted by the pianistic flights of my twelve-year-old daughter, Suzanna. "How does she make her fingers go so fast?" was the question that occurred to me when I interrupted my listening long enough to watch her play. I read everything I could about the subject and finally realized I would never find the answer until I took myself to the piano to find out.

As a beginning student I imagined that music learning would go just as it is depicted by music teachers: begin with simple pieces, learn the names of the notes, practice scales and exercises, memorize, play in student recitals, then move on (shakily or steadily) to more and more difficult music. But over the course of five years of study my personal experience deviated further and further from this itinerary. It was not that I was fast or slow, musical or unmusical; at various times I was each of those. Despite the guidance of a seasoned teacher armed with the highly polished canons of music pedagogy, the whole enterprise was rife with unexpected turns, detours, and diversions. Inside me, it seems, there was already a plan for being a musician--a modest one, but a plan nonetheless: the protocols of music had simply set the specific cognitive, motor, emotional, and social terms according to which hand and finger movements that were initially unsure and clumsy would gradually become more accurate and fluent. As I hope to demonstrate--even to the satisfaction of music teachers--I might as easily have been in a woodcarving class, or learning how to arrange flowers or build racing-car engines.

After several years of piano study I began to see musicians as patients. Most came expecting that a doctor with musical training would better understand their physical problems than one without such experience. Later, the "hand cases" also came from restaurants, banks, police stations, dental offices, machine shops, beauty parlors, hospitals, ranches. All came for the same simple reason: they could not do their jobs without a working pair of hands.

A major turning point in my thinking about the hand came as the result of a presentation I made to a group of musicians about a particularly difficult and puzzling problem called musician's cramp. I had brought along a video clip to show during the talk. It was a brief clinical-musical medley of hands that had either been injured or had mysteriously lost their former skill; formerly graceful, lithe, dazzlingly fast hands could barely limp through the notes they sought to draw out of pianos, guitars, flutes, and violins. Just a few minutes after the film began, a guitarist in the audience fainted. I was amazed. This was not the sort of grotesque display one sometimes sees in medical movies; these were just musicians unable to play their instruments. When the same thing happened at subsequent presentations--a second and then a third time--I was genuinely puzzled. I decided I must have missed subtleties or hidden meaning in these films apparent only to very few viewers. It was not until much later that I came to understand the real message these fainting musicians were expressing.

I now understand that I had failed to appreciate how the commitment to a career in music differs from even the most serious amateur interest. Although I had worked very hard as a beginning piano student, took the work seriously and spent a great deal of time at it, it was not my life. Consequently I did not anticipate the profound empathy for the injured musicians that would be felt by some viewers of these films. Moreover--and this is a lesson I learned, one person at a time, as I conducted interviews with nonmusicians for this book--when personal desire prompts anyone to learn to do something well with the hands, an extremely complicated process is initiated that endows the work with a powerful emotional charge. People are changed, significantly and irreversibly it seems, when movement, thought, and feeling fuse during the active, long-term pursuit of personal goals.

Serious musicians are emotional about their work not simply because they are committed to it, nor because their work demands the public expression of emotion. The musicians' concern for their hands is a by-product of the intense striving through which they turn them into the essential physical instrument for realization of their own ideas or the communication of closely held feelings. The same is true of sculptors, woodcarvers, jewelers, jugglers, and surgeons when they are fully immersed in their work. It is more than simple satisfaction or contentedness: musicians, for example, love to work and are miserable when they cannot; they rarely welcome an unscheduled vacation unless it is very brief. How peculiar it is that people who normally permit themselves so little rest from an extreme and, by some standards, unrewarding discipline cannot bear to be disengaged from it. The musician in full flight is an ecstatic creature, and the same person with wings clipped is unexploded dynamite with the fuse lit. The word "passion" describes attachments that are...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and...

The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679412492I5N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0679412492I5N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. Good dust jacket. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Artikel-Nr. K11Q-01831

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Hand

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. GRP64459484

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Hand

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 4074630-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Hand

Anbieter: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. 1st. Ships from the UK. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. GRP64459484

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture

Anbieter: Bookplate, Chestertown, MD, USA

Soft cover. Zustand: Near Fine. 1st Edition. Clean, unmarked copy with crease-free spine and sharp corners. BP/Climate Change. Artikel-Nr. ABE-1632189878946

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Hand How its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture

Anbieter: True Oak Books, Highland, NY, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: Very Good. First Edition; Fourth Printing. 397 pages; B&W illustrations. Light rubbing to DJ. Very minor finger smudges to the exterior edges of textblock. ; - Your satisfaction is our priority. We offer free returns and respond promptly to all inquiries. Your item will be carefully cushioned in bubble wrap and securely boxed. All orders ship on the same or next business day. Buy with confidence. Artikel-Nr. HVD-51468-A-0

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. GOR005796907

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar