Inhaltsangabe

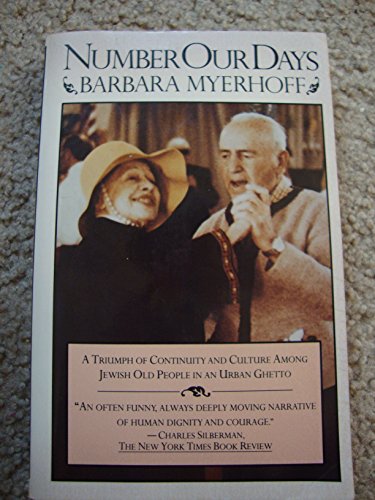

When noted anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff received a grant to explore the process of aging, she decided to study some elderly Jews from Venice, California, rather than to report on a more exotic people. The story of the rituals and lives of these remarkable old people is, as Bel Kaufman said, "one of those rare books that leave the reader somehow changed."

Here Dr. Myerhoff records the stories of a culture that seems to give people the strength to face enormous daily problems -- poverty, neglect, loneliness, poor health, inadequate housing and physical danger. The tale is a poignant one, funny and often wise, with implications for all of us about the importance of ritual, the agonies of aging, and the indomitable human spirit.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

The chairperson of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Southern California, Dr. Myerhoff collaborated on a film about her work while she was doing the research for Number Our Days. It won the 1977 Academy Award for best short documentary. Her last book, Peyote Hunt, was nominated for a National Book Award.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

CHAPTER ONE

"So what do you want from us here?"

Every morning I wake up in pain. I wiggle my toes. Good. They still obey. I open my eyes. Good. I can see. Everything hurts but I get dressed. I walk down to the ocean. Good. It's still there. Now my day can start. About tomorrow I never know. After all, I'm eighty-nine. I can't live forever.

Death and the ocean are protagonists in Basha's life. They provide points of orientation, comforting in their certitude. One visible, the other invisible, neither hostile nor friendly, they accompany her as she walks down the boardwalk to the Aliyah Senior Citizens' Center.

Basha wants to remain independent above all. Her life at the beach depends on her ability to perform a minimum number of basic tasks. She must shop and cook, dress herself, care for her body and her one-room apartment, walk, take the bus to the market and the doctor, be able to make a telephone call in case of emergency. Her arthritic hands have a difficult time with the buttons on her dress. Some days her fingers ache and swell so that she cannot fit them into the holes of the telephone dial. Her hands shake as she puts in her eyedrops for glaucoma. Fortunately, she no longer has to give herself injections for her diabetes. Now it is controlled by pills, if she is careful about what she eats. In the neighborhood there are no large markets within walking distance. She must take the bus to shop. The bus steps are very high and sometimes the driver objects when she tries to bring her little wheeled cart aboard. A small boy whom she has befriended and occasionally pays often waits for her at the bus stop to help her up. When she cannot bring her cart onto the bus or isn't helped up the steps, she must walk to the market. Then shopping takes the better part of the day and exhausts her. Her feet, thank God, give her less trouble since she figured out how to cut and sew a pair of cloth shoes so as to leave room for her callouses and bunions.

Basha's daughter calls her once a week and worries about her mother living alone and in a deteriorated neighborhood. "Don't worry about me, darling. This morning I put the garbage in the oven and the bagels in the trash. But I'm feeling fine." Basha enjoys teasing her daughter whose distant concern she finds somewhat embarrassing. "She says to me, 'Mamaleh, you're sweet but you're so stupid.' What else could a greenhorn mother expect from a daughter who is a lawyer?" The statement conveys Basha's simultaneous pride and grief in having produced an educated, successful child whose very accomplishments drastically separate her from her mother. The daughter has often invited Basha to come and live with her, but she refuses.

What would I do with myself there in her big house, alone all day, when the children are at work? No one to talk to. No place to walk. Nobody talks Yiddish. My daughter's husband doesn't like my cooking, so I can't even help with meals. Who needs an old lady around, somebody else for my daughter to take care of? They don't keep the house warm like I like it. When I go to the bathroom at night, I'm afraid to flush, I shouldn't wake anybody up. Here I have lived for thirty-one years. I have my friends. I have the fresh air. Always there are people to talk to on the benches. I can go to the Center whenever I like and always there's something doing there. As long as I can manage for myself, I'll stay here.

Managing means three things: taking care of herself, stretching her monthly pension of three hundred and twenty dollars to cover expenses, and filling her time in ways that have meaning for her. The first two are increasingly hard and she knows that they are battles she will eventually lose. But her free time does not weigh on her. She is never bored and rarely depressed. In many ways, life is not different from before. She has never been well-off, and she never expected things to be easy. When asked if she is happy, she shrugs and laughs. "Happiness by me is a hot cup of tea on a cold day. When you don't get a broken leg, you could call yourself happy."

Basha, like many of the three hundred or so elderly members of the Aliyah Center, was born and spent much of her childhood in one of the small, predominately Jewish, Yiddish-speaking villages known as shtetls, located within the Pale of Settlement of Czarist Russia, an area to which almost half the world's Jewish population was confined in the nineteenth century. Desperately poor, regularly terrorized by outbreaks of anti-Semitism initiated by government officials and surrounding peasants, shtetl life was precarious. Yet a rich, highly developed culture flourished in these encapsulated settlements, based on a shared sacred religious history, common customs and beliefs, and two languages -- Hebrew for prayer and Yiddish for daily life. A folk culture, Yiddishkeit, reached its fluorescence there, and though it continues in various places in the world today, by comparison these are dim and fading expressions of it. When times worsened, it often seemed that Eastern Europe social life intensified proportionately. Internal ties deepened, and the people drew sustenance and courage from each other, their religion, and their community. For many, life became unbearable under the increasingly reactionary regime of Czar Alexander II. The pogroms of 1881-1882, accompanied by severe economic and legal restrictions, drove out the more desperate and daring of the Jews. Soon they were leaving the shtetls and the cities in droves. The exodus of Jews from Eastern Europe swelled rapidly until by the turn of the century, hundreds of thousands were emigrating, the majority to seek freedom and opportunity in the New World.

Basha dresses simply but with care. The purchase of each item of clothing is a major decision. It must last, should be modest and appropriate to her age, but gay and up-to-date. And, of course, it can't be too costly. Basha is not quite five feet tall. She is a sturdy boat of a woman -- wide, strong of frame, and heavily corseted. She navigates her great monobosom before her, supported by broad hips and thin, severely bowed legs, their shape the heritage of her malnourished childhood. Like most of the people who belong to the Aliyah Center, her early life in Eastern Europe was characterized by relentless poverty.

Basha dresses for the cold, even though she is now living in Southern California, wearing a babushka under a red sun hat, a sweater under her heavy coat. She moves down the boardwalk steadily, paying attention to the placement of her feet. A fall is common and dangerous for the elderly. A fractured hip can mean permanent disability, loss of autonomy, and removal from the community to a convalescent or old age home. Basha seats herself on a bench in front of the Center and waits for friends. Her feet are spread apart, well-planted, as if growing up from the cement. Even sitting quite still, there is an air of determination about her. She will withstand attacks by anti-Semites, Cossacks, Nazis, historical enemies whom she conquers by outliving. She defies time and weather (though it is not cold here). So she might have sat a century ago, before a small pyramid of potatoes or herring in the marketplace of the Polish town where she was born. Patient, resolute, she is a survivor.

Not all the Center women are steady boats like Basha. Some, like Faegl, are leaves, so delicate, dry, and vulnerable that it seems at any moment they might be whisked away by a strong gust. And one day, a sudden wind did knock Faegl to the ground. Others, like Gita, are birds, small and sharp-tongued. Quick, witty, vain, flirtatious, they are very fond of singing and dancing. They once were and will always be pretty girls. This is one of their survival strategies. Boats, leaves, or birds, at first their faces look alike. Individual features are blurred...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Number Our Days (Touchstone Book)

Number Our Days: A Triumph of Continuity and Culture Among Jewish Old People in an Urban Ghetto

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Artikel-Nr. Q05A-02966

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Number Our Days: A Triumph of Continuity and Culture Among Jewish Old People in an Urban Ghetto

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. 1st Touchstone Edition 1980. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Artikel-Nr. 0671254308-11-1

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Number Our Days

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Touchstone Ed. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. GRP97997923

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Number Our Days

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. 1st Touchstone Ed. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 4349370-20

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Number Our Days

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. 1st Touchstone Ed. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 3374463-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Number Our Days: A Triumph of Continuity and Culture Among Jewish Old People in an Urban Ghetto

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0671254308I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Number Our Days: A Triumph of Continuity and Culture Among Jewish Old People in an Urban Ghetto

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0671254308I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Number Our Days (Touchstone Books)

Anbieter: AwesomeBooks, Wallingford, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Number Our Days (Touchstone Books) This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Artikel-Nr. 7719-9780671254308

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Number Our Days (Touchstone Books)

Anbieter: Bahamut Media, Reading, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Artikel-Nr. 6545-9780671254308

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Number Our Days

Anbieter: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Very Good. 1st Touchstone Ed. Ships from the UK. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 4349370-20

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar