Verwandte Artikel zu The Best American Spiritual Writing 2004 (The Best...

Inhaltsangabe

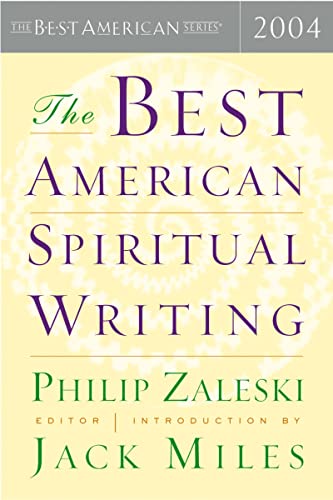

Since its inception in 1915, the Best American series has become the premier annual showcase for the country's finest short fiction and nonfiction. For each volume, a series editor reads pieces from hundreds of periodicals, then selects between fifty and a hundred outstanding works. That selection is pared down to twenty or so very best pieces by a guest editor who is widely recognized as a leading writer in his or her field. This unique system has helped make the Best American series the most respected -- and most popular -- of its kind.

The latest addition to the esteemed Best American series is a collection of the best spiritual writing of the year, introduced by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jack Miles and including both prose and poetry. Series editor Philip Zaleski has chosen the volume's pieces with an eye to spirituality's many guises, from its impact on personal relationships and the environment to politics, creativity, and literature. Christian, Muslim, Jewish, secular, and pan-Hindu perspectives are all represented in these pieces, which have been selected from both mainstream and more specialized periodicals.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Best American Spiritual Writing 2004

By Philip ZaleskiHoughton Mifflin Company

Copyright © 2004 Philip ZaleskiAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780618443031

Introduction

"Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?" And calling to him a child,

he put him in the midst of them, and said, "Truly I say to you, unless you turn

and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.

Whoever humbles himself like this child, he is the greatest in the kingdom of

heaven."

— Matthew 18:2–4

By now the word spirituality ought not embarrass me, but like the

word mommy, it still does. Mommy has its place and, especially, its

time; but we cringe a bit, don"t we, when we hear an adult unselfconsciously

say, "Mommy phoned this morning." The word is out

of place, or past its time. Adults don"t talk that way. Or shouldn"t.

Or so we think. Perhaps adults suf?ciently serene in their adulthood

do not blush at mommy. But because spirituality is a word that I

?rst heard in a little world that shaped me as powerfully as a second

family, a world that I left behind only after a struggle, this word carries

for me some of the same baggage as mommy. The contributions

to this year"s Best Spiritual Writing are varied, authentic, engaging,

and repeatedly surprising, yet for me, I confess, they summon up

the memory of a time when spirituality and adulthood seemed antithetical.

I was introduced to spirituality at the age of fourteen as a brother

in the devotional fraternity called the sodality (from the Latin

sodalis, companion) that was a part of life at all Jesuit secondary

schools. Starting in freshman year, we sodalists were introduced to

the school of spirituality called Ignatian — techniques of prayer

and meditation developed by Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the

Society of Jesus (the Jesuits). Back in 1956, our initiation into men-

tal prayer, as the beginner"s exercise in Ignatian spirituality was then

called, began in much the same way an introduction to Pilates

training might now — that is, in a group and under the direction

of a trainer.

The ?rst step, once we had gathered in the chapel at the appointed

hour, was the recitation of one of the Roman Catholic

prayers that we all knew by heart. This in itself created a mild sense

of fraternity, relocated us, and brought us to a kind of preliminary

focus. The second step was a minute or two of silence. The third

step was the instruction "Place yourself in the presence of God,"

about which more below. The fourth step was another interlude of

silence — still brief, but a little longer than the ?rst one. The ?fth

step was the leader"s presentation in a ?ve-minute talk of a subject

suitable for meditation. A typical subject would be Christ"s prayer

during his agony in the Garden of Gethsemane: "Father, if it be

possible, let this cup pass from me, but not my will but thine be

done." The priest — the leader was always a priest on the faculty of

the school — might evoke darkness, the chill of the night, the danger,

and so forth, and direct our attention to Christ"s honesty and

his courage. Then would begin the sixth step in the exercise, the

central period of silence or mental prayer proper. Rather than asking

God for something, mental prayer was simply thinking about

something in the presence of God and awaiting what might ensue

within the mind. After the lapse of nearly ?fty years, I cannot recall

the exit formula — there was one — that was spoken after perhaps

?fteen minutes to signal the end of the central exercise. Coming

out of mental prayer felt a bit like awakening from hypnosis. Returned

to ourselves, we recited a concluding prayer in unison and

tramped out of the chapel for the rest of the school day.

What transpires in the minds of fourteen-year-old boys instructed

to place themselves in the presence of God? Twenty years

later, a friend"s son told us of a study allegedly proving that sixteen-year-

olds experience a sex-related thought every thirty seconds. My

friend was surprised. I was not. And to me, the chapel at St.

Ignatius High School was, in memory, the place where I seemed

most aware of the intervals. Yet I testify that the command "Place

yourself in the presence of God" produced a shift of consciousness

that the succession of tumescence and detumescence did not undermine.

Did we even believe in God? At one point in John Updike"s ?rst

novel, The Centaur, an inspired high school teacher is preaching —

no other verb will quite do — the grand sweep of evolution from

the Big Bang to the rise of human consciousness. The novelist directs

our attention to a boy in a back seat whose gross sex-preoccupation

seems to undercut the nobility of the lecture. But behind

the character in the novel, there broods the novelist himself.

Updike is a Christian inspired in spite of himself by this godless vision.

Were he an atheist, he would be inspired in spite of himself by

the Christian vision. The text of belief and unbelief seems so often

to read like a giant palindrome.

Rather than by the Christian vision per se, I myself was entranced

by the esprit de corps of the Jesuit order. Over a ten-year period beginning

with my eighteenth year, the Jesuits turned me into an intellectual

of sorts, but they ?rst turned me into a fellow Jesuit

through two full years of an intense initiation into Ignatian spirituality.

This was an experience that, as I would later conclude, reversed

my normal movement from adolescence to adulthood and

turned me, powerfully albeit temporarily, from an adolescent back

into a child. And though I was, to say the least, confused and embarrassed

by the reversal, I return to it in memory with a kind of

longing.

A month after entering the order, I was led through the Spiritual

Exercises of St. Ignatius — a month of silence interrupted by only a

few hours of conversation every six or seven days. For the remainder

of that two-year novitiate, I rose at ?ve every morning and meditated

in silence for an hour at a desk provided with a kneeler before

walking silently to the chapel for Mass and then from the

chapel to the refectory for a silent breakfast. My life included no

television, no radio, no newspapers or magazines, and no reading

material other than books on, what else, spirituality. All my needs

— food, shelter, clothing, health care, recreation, and companionship

— were provided for. In all those regards, I had, as never since

early childhood, literally nothing to worry about; and for long minutes

— in the chapel, for example, after the morning"s meditation

had ended but before daily Mass began — nothing to think about,

either. And I began to like it that way. Against the predictions of

some, I began to like having nothing on my mind.

Besides practicing Ignatian meditation every morning, a novice

attended more general lectures on Christian spirituality. One

learned about the history of monasticism and about the various

schools of spirituality. One read classics in the related literature.

One learned of the via purgativa, the via contemplativa, and, for the

sainted few, the via unitiva. As beginners, we were on the via

purgativa. Purgative asceticism — fasting, mild (and closely controlled)

self-?agellation, and the use of the "discipline," a kind of

barbed bracelet worn for an hour or two around the thigh —

would help us get started.

Did it take? It is easy to answer that it did not. By divers paths,

most of those who started out with me to become Jesuits are now

ex-Jesuits. But, yes, something did take, though not in the way I

once thought it did. Novitiate life, often silent and solemn, was not

always so; and this matters more in retrospect than it did at the

time. A Jesuit of the generation before mine entitled his memoir of

Jesuit training I"ll Die Laughing. I have never, before or since,

laughed with such abandon as I did during those two years. Nor

have I ever lived so physical a life, a life of sports played to such joyous

exhaustion. Never before or since have I lived a life in which so

many hours were spent exuberantly out-of-doors or in which I

seemed to feel the passing of the seasons in every pore of my skin.

As for sex, though I know now that others have other tales to tell,

my experience during those ?rst two years consisted entirely in

noctural emissions: never a dalliance with another boy, never an

act of masturbation. We were given three rules to follow: tactus

(Latin for "touch"), the rule forbidding us to touch one another

(tagging in tag football or collisions in basketball or handball were

exceptions to the rule); "particular friendship," a rule that, in effect,

meant that we were to strive to treat all the brethren with

equal affection; and "custody of the eyes" — that is, no "meaningful"

gazing. These three rules, which at my novitiate seemed to be

strictly observed, preserved chastity pretty effectively. But in effect

they made us act as if we had yet to enter puberty; and in saying

this, I return to the troubling question with which I began. Must

one become a child to enter the kingdom of heaven?

At Harvard in the turmoil of the late 1960s, still a Jesuit but now a

Harvard graduate student as well, I awoke one morning to an

oddly frightening thought: I could not recall when I had last had a

wet dream. Why should this matter? I asked myself. After all, I had

taken a vow of celibacy. The answer that came — not instantaneously

but quickly enough — was that I had not authentically renounced

sex but only, somehow, inde?nitely postponed it. When

vowing celibacy, I had unconsciously made (to use a phrase from

Jesuit casuistry) a mental reservation. But I had pronounced my

vows all of eight years earlier. Time was ?eeting! Though I was only

twenty-seven, the physical change I had noticed was enough to

send a simple but chilling message: I would not be forever young.

And from that morning on, something began to unravel.

Ignatius Loyola built his spiritual exercises around the transformation

that he had brought about in himself while recovering

from a crippling war injury. But at the time of this transformation,

the charismatic Basque had behind him years of life as a courtier

and as a soldier. He had fathered a child. A novice in the spiritual

life, he was anything but a sexual novice. But could the regimen

that turned this sexually experienced if not, in fact, somewhat

debauched courtier into a monk be imposed on virginal Irish-

American boys to the same transformative effect? What was there

to transform?

In the 1960s, younger American Jesuits had already begun to object

that traditional Jesuit training infantilized them. But for the

sexual sharpening of that point and its linkage to Ignatius himself,

I am indebted not to them but to a Jewish classmate at Harvard.

Jeremy (as I will call him) was one of surprisingly few Jews who

brought no rabbinical training and no Jewish religious commitment

with them into Harvard"s Hebrew Bible program. His path to

the Tanakh had led not from any yeshiva but rather from an undergraduate

love affair with Israeli Hebrew as a rapidly evolving literary

language. Jeremy read the dense Hebrew prose of S. Y. Agnon

for pleasure and, to universal amazement, without a dictionary. His

prickly manner with the religious Jews in our classes presaged a battle

that he would join only later, but it is always easier to see another"s

humpback. When it came to Catholicism, Jeremy had an

unforced, intuitive, sympathetic, and in the end quite correct understanding

of what was eating at his Jesuit classmates.

Jeremy was a good friend, and I remember him fondly. All the

same, I blushed hot when he made his historical/sociological observation.

He was gentle, he was wry, but I was morti?ed anyway.

One way to state the human condition, I submit, is to assert that for

our species meaningless sex is impossible. However mere we would

like mere sex to be, some sort of meaning always crowds in on it.

Sex can represent strength, youth, beauty, health, love, safety, consolation,

wealth, power, transcendence, oblivion, escape — a list

that any reader of this sentence can lengthen. For me, at that time

in my life, it represented adulthood. I could not begin to be an

adult, I thought, until I ceased to be a virgin. It was sexual experience

that separated the men from the boys, and I was still, in a

painfully unbecoming sense of the phrase, just one of the boys.

As this transitus got under way, the Society of Jesus and everything

I had learned about spirituality in my speci?cally Jesuit training

came to seem part of an embarrassingly prolonged boyhood. It

mattered not a little that in the 1960s the word spirituality, ubiquitous

in Roman Catholic piety, was still rare in Protestant, Jewish,

and secular discourse. The difference of dialect mattered because

at just this time, in the wake of the Second Vatican Council and of

the election of John F. Kennedy, American Catholics as a population

were emerging self-consciously and awkwardly from their

socioreligious ghetto and looking to take their natural place in the

larger American society. To use the word spirituality was, for me, to

ring the leper"s bell: Catholic! Catholic! Worse, it was to hint at an

appalling defect of masculinity: spirituality as the chaste seminarian"s

substitute for physicality. I felt like Hester Prynne wearing a V

for Virgin instead of an A for Adulteress.

When I wrote my Jesuit superior in Chicago (though studying at

Harvard, I belonged to the Chicago "province" of the order), he

wrote back asking if I had discussed with my spiritual director a request

for dismissal from the Society. (A Jesuit who wanted to depart

on good terms did not just quit or walk out; he requested dismissal.)

The man"s question was perfectly honorable and reasonable

within the assumptions of the order, and I recognized it as

such. Yet spiritual director prompted the same sort of wince that spirituality

prompted. What would people think — the people I wanted

to meet, the people I wanted to think me one of them — if they

knew I had something called a spiritual director? At some emotional

level, it was as if a young man, planning to go abroad, were to

notify his father tersely of his intentions and hear back solicitously,

"But have you talked this over with Mommy?"

Yet consultation with a spiritual director was a step that I felt conscience-

bound to take. If this was to be a divorce, and that seemed

pretty likely, I wanted it to be an amicable divorce. Giving spiritual

direction a chance constituted good faith in the secular sense of

the phrase. To my good fortune, I found my way to a brilliant and

rather worldly Jesuit philosopher, then a scholar in residence at a

posh psychiatric clinic in the Berkshires. An afternoon with him, as

the snow deepened outside, effectively became my exit interview

from the order. In memory, the soundtrack for the long drive back

to Boston is James Taylor"s "Sweet Baby James," a song mysteriously

about adulthood and rock-a-bye infancy, not to speak of the

Berkshires, Boston, snowy December, and an un?nished journey to

an unknown destination.

Adulthood is a meaning that sexual experience can bear at most

only brie?y and once. As a transition to adulthood, losing one"s virginity

is rather like disembarking from a ship. Once one is ashore,

even if one is the last to disembark, one is ashore for good. The

thing is done. But in my case, as it happens, other meanings followed

on apace.

Not long after leaving the order and the church as well, I began

to read a good deal about Buddhist meditation. I attended a number

of lectures and began to meditate regularly. I found appealing,

even consoling, the doctrine of anatta, according to which the self

is an illusion, a transitory event "co-dependently originated" from

multiple starting points. I found plausible the claim that the illusion

of self is preserved only in normal consciousness, wherein

arises normal desire, the origin of all pain, and that liberation is

accomplished by "the slaying of the mind," vividly pictured as a

hyperactive monkey hopping from branch to branch. Unlike Jesuit

meditation, Buddhist meditation is not an attempt to think

seriously and at length about something such as Jesus" agony in

Gethsemane but rather an attempt to kill the monkey — to halt

ordinary thinking altogether and subside into a protracted precognitional

or extra-cognitional state. The Buddhist-inspired exercises

that I undertook at this time produced an effect that seemed

different from but experientially just as real as the more familiar Jesuit

effect of placing myself in the presence of God. But what I

found most arresting was the fact that the brief periods (only some

minutes in duration) during which I seemed to achieve what was

referred to as mindfulness resembled nothing so much as the sense

of mental emptiness that I had by then experienced during peak

moments in sexual intercourse.

It was only years later that I learned of vajrayana Buddhism and

the cosmology behind ego-obliterating tantric sex. The Los Angeles

County Museum of Art is home to the Heeramoneck collection

of Tibetan art, including a stunning array of esoteric mandalas

portraying ecstatic divine copulation in a way that is intended to

erase not just the distinction between gods and men but also that

between self and world and, ultimately, between order and chaos.

Had I happened into such an experience of ego-erasure at the

time when I surrendered within the same brief period my virginity

and the Jesuit cosmos that had engulfed me from puberty on? I

wondered: perhaps so. But by the time the idea occurred to me, I

had turned the page in a dozen ways. I can only say that during my

earlier "Buddhist period," though I was willing to take it on faith

that true enlightenment is only arduously achieved, I could not

deny a certain sense of déja vu when taking instruction. If, to quote

a well-known Buddhist saying, the Buddha at the moment of enlightenment

was like a deer in the deer park, if that state of mind

— a state of animal rather than human consciousness — is the goal

of Buddhist meditation, then Buddhism may be respectfully and

uninvidiously characterized as an attempt to exit the normal adult

spiritual condition. But this seemed an exit that I had by then experienced,

however ?eetingly, in two quite different settings.

Or so I thought.We give human children little stuffed animals to

play with because, in a way, children are little animals. Their consciousness

has not yet matured to the adult human state. Their little

minds are not yet jumping from branch to branch with adult human

agility. Buddhism has always seemed to me an attempt not

merely to return to a childlike state of consciousness — call it the

stuffed-animal state — but boldly to progress or descend past that

state to something even more devoid of human ideation. I honor

that effort, and yet I would add that descending only as far as the

stuffed-animal state takes some doing; and this is the experience

that I seem to recall in the luminosity of my ?rst Jesuit years.

I begin with the observation that though we were not mistaken as

Jesuits in our late twenties to object that our training had juve-

nilized us, juvenilization has more than one meaning. Yes, we had

been excused from adult responsibility in a way that left us super-

?cially and temporarily ill equipped to assume such responsibility

later. But that same deprivation — joined during a period of

two full years with strict sexual abstinence and with a deprivation

from all else that might have given our incipiently adult minds

whereon to think — ushered us back through the gates of puberty

into a kind of induced second latency. And that second latency,

however arti?cial, remains in memory a distinct, vivid, and deeply

attractive spiritual state. We were not like deer in the deer park,

no, but we were, after all, in surprisingly close approximation to

the spiritual condition of prepubescent children. Everyone saw

this about us. Everyone, even elderly retired Jesuits who had been

through the experience themselves years earlier, shook their heads

and laughed when they saw it in us. But there it was. Think of it, if

you will, as standing on your head. Headstanding may be crazy, but

it is certainly possible, and its effect upon the brain, whether you

call the effect bene?cial or not, is unlike that of any other exercise

you can perform. At the time, I liked it rather well.

All this was, you will understand, a long time ago. I now have a

daughter at Berkeley. Next year, my wife and I will celebrate the silver

anniversary of our wedding. But when I am asked to address

myself to "spiritual writing," much of this tangled process crowds its

way back in. There was a time not too long ago when I would have

tried to talk about it without using the word spirituality. But by a

roundabout path, I have come to a point where I can speak some of

the old words without the old fear of being somehow tainted, disquali

?ed from competing in the larger world, or, worse, dragged

all the way back in.

The memory of spiritual intensity in childhood has been for one

writer after another the touchstone for all spiritual experience worthy

of the name. Jesus was far from the only one. I spoke above of

sports played to joyous exhaustion and of the seasons of the year

felt in every pore of the skin. Whom does that bring to your mind?

It brings the poet Dylan Thomas to mine. Who has spoken better of

that state of heightened but joyfully unreckoning sensitivity? "In

the sun born over and over," he wrote, "I ran my heedless ways."

The novitiate stood on a bluff overlooking a river. Leaving the

park-like grounds, we would hike through woods cut by cold creeks

to a farmhouse the novitiate owned, situated on a remote hilltop.

Remembering these hikes and the larky feeling of boys on a holiday,

I think of Wordsworth in a dozen passages like:

The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion; the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood,

Their colors and their forms, were then to me

An appetite; a feeling and a love,

That had no need of a remoter charm,

By thoughts supplied, nor any interest

Unborrowed from the eye.

Many from all backgrounds cherish some such memory from

childhood. But granting that the intensity of childhood experience

is a recognizable state, even a familiar one, one must still ask: Is it

also a state to which the adult can return after the natural moment

for it has come and gone? Is it possible to create a spiritual discipline

to turn the man, even the sexually ardent young man, back

into a boy? That is the question — the question of whether an intense

but transitory personal experience can ever be replicated

and then built into an ongoing adult life.

Never completely, I would answer, but perhaps partially. As Jesuit

novices, it seems to me that we tried our best. And we had a warrant

for our attempt in the Gospel passage that I have placed as an epigraph

to this essay. Many of those who are revered as spiritual leaders

radiate a youthfulness that age cannot touch, a maturity beyond

mere adulthood. As Jeremy suggested, it may be a mistake to attempt

this step beyond adulthood before reaching adulthood in

the simpler sense. Hinduism with its rich and rooted acknowledgment

of the stages of life may be wiser here than Catholic Christianity.

But if one does try to be, so to speak, young before one"s time,

well, you may count on it: something will happen. Racing ahead

that way is, perhaps, a bit like reading a great classic before you are

old enough to appreciate it. I read King Lear for the ?rst time when

I was ?fteen. It means incomparably more to me now than it did

then, but it meant something to me even then. This is what I meant

when I said above that "something took" in the Jesuit novitiate.

The fact that I grew accustomed to hearing "formed" Jesuits,

caught up in the swirl of their later lives as teachers, administrators,

lab supervisors, drama coaches, and what have you, speak of the

novitiate as a lost world suggests to me that the spiritual effect of

which I speak was a secondary, largely unconscious effect. Primarily

and consciously, we were learning and practicing the rationalized

Ignatian spirituality of mental prayer. Perhaps at the peak

moments of that spirituality, such as the nature meditation that

comes at the conclusion of the Spiritual Exercises, the two did

seem brie?y to work in tandem. But more often, they did not; and

the more powerful experience was the one less attended to, the

one that lingers as an indelible memory, however transitory it may

have been as a spiritual condition.

As I said above, it was the esprit de corps of the Society of Jesus that

made me, at the age of seventeen, want to enlist. How powerfully,

as adolescents leave their families behind, they yearn to belong to

something else! And how painful it can be not to make the team,

not to be admitted to the fraternity, not to be chosen for the cast.

At such a moment, a boy or girl feels not so much rejected as orphaned.

The hoped-for replacement family has turned one out.

Adults, too, often have a desire to belong to something larger than

themselves, but theirs is a tamed and domesticated version of the

awful adolescent craving. The developed adult appetite (capacity

might be a better word) for group identity doesn"t eat at the

achieved adult but feeds him. The earlier, more rampant appetite

— for those who are lucky enough to make the team or the fraternity

or the cast — can easily go beyond nurture to intoxication. It

certainly did for me.

Years after leaving the Jesuits, I learned with a faint jolt of recognition

that the motto of the French Foreign Legion is Legio patria

mea: "The legion is my fatherland." The legion and not, as one

might expect, France. This brought a shock of recognition because

my own earlier motto could so easily have been Societas ecclesia mea:

"The Society is my church." "The Society" is what Jesuits call the order

among themselves. That it is "of Jesus" goes without saying. But

as with young legionnaires, so with young Jesuits: in the end, ?rst

things must come ?rst. If you have your doubts about France, you

don"t belong in the Legion, however exciting you may have found

it. And if you have your doubts about the Church of Rome, you

don"t belong in the Society of Jesus, either.

Ten years after leaving the Jesuits, I rati?ed a process already well

under way by marrying in the Episcopal Church. I had concluded

by then both that I could not avail myself of the spiritual resources

of Buddhism as well as I could those of Christianity and, more basically,

that agnostic disaf?liation, the default option for my generation,

was an intellectually unwarranted impoverishment of life.

Spiritual life in the Episcopal Church has been, for me, like life

lived in a ramshackle but still surprisingly functional old manse. As

an Episcopalian, I am accommodated as the adult I must ever be,

yet given repeated, ?eeting but pungent occasions to be, without

shame, a spiritual child again.

I know that the Episcopal Church is not for everyone, but then

what is? This seems a ?ippant question, but I mean to ask it seriously

with reference to this anthology of spiritual writing. Of its

contributors, one may know, guess, or suspect that several, at least,

are committed to developed traditions or disciplines that, for their

adherents or practitioners, have historically been answers rather

than questions, intended for the many rather than for the few. But

in the main, what the contributors choose to write of here is, as I

might put it, the vestibule rather than the sanctuary. One detects a

pluralistically chastened awareness that comparable experiences,

as they come to be preserved and implemented, may lead to incomparable,

incompatible rationalizations. These, too, can be

shared, but never quickly, never easily, and often at some risk of offense.

The most powerful statement collectively made by this anthology

is thus less an assertion of some such tradition or discipline than it

is a negation of the mentioned default position in American spiritual

life. Again and again in these pages, we ?nd an American man

or woman experientially interrupted in and then dislocated from

the stultifying routine of normal American materialism. Taken together,

the collection thus bespeaks a poignant readiness to take

leave of the consumer society whose cosmology may be Big Bangawesome

but whose ideology rarely gets much past "When the going

gets tough, the tough go shopping." Just after World War II,

Americans believed that science had won the war and saved the

world from tyranny and that the material plenty bestowed by science

("Better Living Through Chemistry" was an advertising slogan

of the day) was an innocent blessing, especially for folks who

had known such tough times so recently. That belief is the spiritual

home, the default Weltanschauung, for most Americans over forty.

But in the ?rst decade of the twenty-?rst century, science seems increasingly

the unwitting destroyer of the world, while the innocence

of American plenty has morphed into obese glut for the few

and dire want for the many. It may be time, then, to leave the default

position, to leave home.

American spiritual writing at its best is, in sum, a pluriform, multifarious

acknowledgment of discom?ture and an opening of exits

into a wider world. These acknowledgments and openings, some of

which involve a doubling back to childhood, are not the consummation

of spirituality, but in their candor and unguarded openness

they are the beginning. The reader is led to this volume, I imagine,

by the question: There must be something more. Where can I ?nd it? The

contributors to this volume answer, in effect: You will ?nd it when it

?nds you. Refuse to deny what you know but consent to how little

that will always be, and, when the moment comes, the sky will open

and the liberating intrusion will descend upon you.

--Jack Miles

Copyright © 2004 by Houghton Mifflin. Introduction copyright © 2004 by

Jack Miles. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin

Company.

Continues...

Excerpted from The Best American Spiritual Writing 2004by Philip Zaleski Copyright © 2004 by Philip Zaleski. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Gratis für den Versand innerhalb von/der Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenEUR 11,53 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für The Best American Spiritual Writing 2004 (The Best...

The Best American Spiritual Writing

Anbieter: Buchpark, Trebbin, Deutschland

Zustand: Sehr gut. Zustand: Sehr gut | Sprache: Englisch | Produktart: Bücher. Artikel-Nr. 1925679/10

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Best American Spiritual Writing 2004

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 10204241-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Best American Spiritual Writing 2004

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 3361298-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Best American Spiritual Writing

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.8. Artikel-Nr. G0618443037I2N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Best American Spiritual Writing 2004

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. 2004 edition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Artikel-Nr. Q14B-01663

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Best American Spiritual Writing 2004

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. 1st edition. 304 pages. 8.00x5.50x0.75 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. x-0618443037

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar