Inhaltsangabe

In this masterpiece of historical fiction by the Nobel Prize-winning Yugoslavian author, a stone bridge in a small Bosnian town bears silent witness to three centuries of conflict.

The town of Visegrad was long caught between the warring Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires, but its sixteenth-century bridge survived unscathed--until 1914 when tensions in the Balkans triggered the first World War. Spanning generations, nationalities, and creeds, The Bridge on the Drina brilliantly illuminates a succession of lives that swirl around the majestic stone arches.

Among them is that of the bridge’s builder, a Serb kidnapped as a boy by the Ottomans; years later, as the empire’s Grand Vezir, he decides to construct a bridge at the spot where he was parted from his mother. A workman named Radisav tries to hinder the construction, with horrific consequences. Later, the beautiful young Fata climbs the bridge’s parapet to escape an arranged marriage, and, later still, an inveterate gambler named Milan risks everything on it in one final game with the devil.

With humor and compassion, Ivo Andric chronicles the ordinary Christians, Jews, and Muslims whose lives are connected by the bridge, in a land that has itself been a bridge between East and West for centuries.

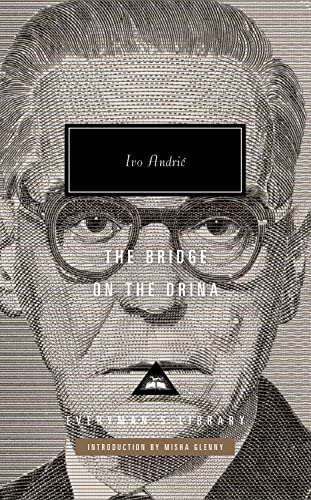

Everyman's Library pursues the highest production standards, printing on acid-free cream-colored paper, with full-cloth cases with two-color foil stamping, decorative endpapers, silk ribbon markers, European-style half-round spines, and a full-color illustrated jacket.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

IVO ANDRIC (1892–1975) was born in Bosnia. He was a distinguished diplomat and novelist, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961. His books include The Damned Yard and Other Stories and The Days of the Consuls.

MISHA GLENNY is an award-winning British journalist who specializes in central and eastern Europe, global organized crime, and cybersecurity. He covered the Balkan Wars during the 1990s and is the auhor of numerous books, including The Fall of Yugoslavia and DarkMarket: How Hackers Became the New Mafia.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

from the INTRODUCTION by Misha Glenny

But the bridge still stood, the same as it had always been, with the eternal youth of a perfect conception, one of the great and good works of man, which do not know what it means to change and grow old and which, or so it seemed, do not share the fate of the transient things of this world.

Ivo Andric was no run-of-the-mill Nobel laureate. He was the only individual personally acquainted with both Gavrilo Princip and Adolf Hitler, the two men whose actions triggered the First and Second World Wars respectively. One could easily adapt Andric’s own biography into a novel as it encapsulates many of the fateful and sometimes fatal dilemmas which people from Central and South-Eastern Europe faced through much of the twentieth century.

After his death in 1975 and again following the wars in Croatia and Bosnia which finally ended in 1995, literary critics and writers from Andric’s home country have engaged in intense discussion about the writer’s literary merits. Contributions to this debate range from the obsequious to the vitriolic. Throw in equally serious reflections about linguistic, political and cultural identity and this discussion becomes hard to understand for those without a decent grasp of the politics and culture of Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia, not to mention the former Yugoslavia in both its royalist and communist variants. The issue is complicated still further because none of the five countries which Andric might have called his ‘home country’ exists any more (the last one collapsed in 1991).

Ivo Andric was born in 1892 in Travnik. This town built into the hills of central Bosnia not far from Mount Vlašic, now a popular tourist destination, commands little attention outside the country. Nonetheless, it played an important part in the country’s history because from the late seventeenth to the mid-nineteenth century, it was the capital of the Ottoman province of Bosnia and seat of the administrative rulers, the viziers. As a consequence for such a small settlement it has an unusual array of architectural riches, some of whose foundations stretch back to the fifteenth century. Both Andric's parents were Catholics, which in the context of Bosnia meant they were Croats. Travnik was a mixed town, consisting mainly of Catholics and Muslims, whom Andric usually refers to as Turks in his writing even though the great majority were actually Slavs who had converted to Islam, along with smaller communities of Orthodox Serbs and Sephardic Jews. Andric never disguised his Croat origins but many years later when he moved to Belgrade, he designated himself a Serb, albeit with no confessional affiliation.

He was born a subject of the Ottoman Empire but in a province which the Sultan in Istanbul, Abdülhamid II, controlled only in name. In 1878, fourteen years before Andric’s birth, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had secured the right to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina as a result of decisions taken at the Congress of Berlin. The Sultan may still have ruled in name but Kaiser Franz Joseph I was now its de facto ruler. Vienna’s subsequent decision to annex the two provinces in 1908, stripping the Sultan of his nominal suzerainty, was a key moment in the events leading up to the outbreak of the First World War.

Andric recognizes this great symbolic break. ‘The year 1908,’ he wrote in The Bridge on the Drina, ‘brought with it great uneasiness and a sort of obscure threat which thenceforward never ceased to weigh upon the town.’ Yet for Andric Habsburg rule had already had a profound impact on Bosnia, especially on its economic and social life.

In fact this had begun much earlier, about the time of the building of the railway line and the first years of the new century. With the rise in prices and the incomprehensible but always perceptible fluctuations of government paper, dividends and exchanges, there was more and more talk of politics.

Andric had a nuanced approach to the Austro-Hungarian occupation. He argued that it led to much needed modernization and economic renewal. His interpretation has not always found favour among critics from both Bosnia and Serbia. Yet Andric was no slavish supporter of the Habsburgs. At key moments in the novel, he identifies future dangers which all the great power manoeuvring implied.

At the time of the original occupation in 1878, Bosnia and Herzegovina was an extremely poor and conservative region. Earlier attempts by a reformist government in Istanbul to break the power of the begs and agas, the Ottoman provincial rulers and landowners, had largely failed. Much of the Catholic, Orthodox and the nominally free Muslim peasantry lived hand to mouth. People’s circumstances in the more affluent towns were often precarious, too. Above all, the pace of life was glacial. So when in the wake of Franz Joseph’s military occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina the Habsburg Double Eagle built its nest in every town and in every village, the sudden invasion of hundreds upon hundreds of Habsburg bureaucrats had a severe psychological impact on the Muslims in particular. Men in neatly cut European uniforms brandished their ink and stamps, demanding endless information about the Empire’s new peoples; poking their noses into the private lives and habits of families whose word until a few months earlier had been more powerful in Bosnia than even the Sultan’s. Snapping orders in strange tongues, they counted houses and measured roads, or more frequently the land upon which new roads and railways would soon be built; they put up signs on buildings and signs on streets in foreign languages. They handed out letters telling young men to report for military service; they indulged in futile administrative rituals about which whole novels have been written; and everywhere they hung portraits of His Imperial and Royal Highness, Franz Joseph I.

Andric recalls this period in The Bridge on the Drina when Muslim elders gather (on the bridge of course) to discuss Vienna’s decision to hold a census:

As always, Alihodja was the first to lose patience.

‘This does not concern the Schwabes’ * *The colloquial word for German speakers.]

faith, Muderis Effendi; it concerns their interests … We cannot see today what all this means, but we shall see it in a month or two, or perhaps a year. For, as the late lamented Shemsibeg Brankovic used to say: “The Schwabes’ mines have long fuses!” This numbering of houses and men, or so I see it, is necessary for them because of some new tax, or else they are thinking of getting men for forced labour or for their army, or perhaps both. If you ask me what we should do, this is my opinion. We have not got the army to rise at once in revolt. That God sees and all men know. But we do not have to obey all that we are commanded. No one need remember his number nor tell his...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für The Bridge on the Drina: Introduction by Misha Glenny...

The Bridge on the Drina: Introduction by Misha Glenny (Everyman's Library Contemporary Classics Series)

Anbieter: Roundabout Books, Greenfield, MA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: New. New from the publisher. Artikel-Nr. 1286489

The Bridge on the Drina: Introduction by Misha Glenny

Anbieter: Kennys Bookstore, Olney, MD, USA

Zustand: New. 2021. Hardback. . . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Artikel-Nr. V9780593320228

Neu kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 15 verfügbar

The Bridge on the Drina

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Hardcover. Zustand: Brand New. 388 pages. 8.50x5.25x1.25 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. xr0593320220

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Bridge on the Drina

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Hardcover. Zustand: Brand New. 388 pages. 8.50x5.25x1.25 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. 0593320220

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Bridge on the Drina: Introduction by Misha Glenny

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Zustand: New. Über den AutorIVO ANDRIĆ (1892-1975) was born in Bosnia. He was a distinguished diplomat and novelist, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961. His books include The Damned Yard and Other Stories and Th. Artikel-Nr. 438817949

Neu kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar