Inhaltsangabe

“A wise, mild and enviably lucid book about a chaotic scene.” —Dwight Garner, The New York Times

“Memoirs of fatherhood are rarely so honest or so blunt.” —Daniel Engber, The Atlantic

“An instant classic.” —M. C. Mah, Romper

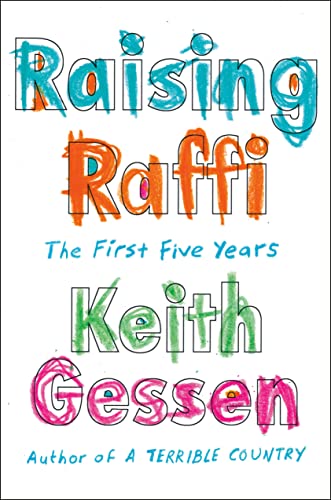

NAMED A MOST ANTICIPATED BOOK OF 2022 BY LIT HUB & THE MILLIONS

An unsparing, loving account of fatherhood and the surprising, magical, and maddening first five years of a son’s life

“I was not prepared to be a father—this much I knew.”

Keith Gessen was nearing forty and hadn’t given much thought to the idea of being a father. He assumed he would have kids, but couldn’t imagine what it would be like to be a parent, or what kind of parent he would be. Then, one Tuesday night in early June, the distant idea of fatherhood came careening into view: Raffi was born, a child as real and complex and demanding of his parents’ energy as he was singularly magical.

Fatherhood is another country: a place where the old concerns are swept away, where the ordering of time is reconstituted, where days unfold according to a child’s needs. Whatever rulebooks once existed for this sort of thing seem irrelevant or outdated. Overnight, Gessen’s perception of his neighborhood changes: suddenly there are flocks of other parents and babies, playgrounds, and schools that span entire blocks. Raffi is enchanting, as well as terrifying, and like all parents, Gessen wants to do what is best for his child. But he has no idea what that is.

Written over the first five years of Raffi’s life, Raising Raffi examines the profound, overwhelming, often maddening experience of being a dad. Gessen traces how the practical decisions one must make each day intersect with some of the weightiest concerns of our age: What does it mean to choose a school in a segregated city? How do you instill in your child a sense of his heritage without passing on that history’s darker sides? Is parental anger normal, possibly useful, or is it inevitably authoritarian and destructive? How do you get your kid to play sports? And what do you do, in a pandemic, when the whole world seems to fall apart? By turns hilarious and poignant, Raising Raffi is a story of what it means to invent the world anew.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Keith Gessen is the author of A Terrible Country and All the Sad Young Literary Men, and is a founding editor of n+1. He has translated or co-translated, from Russian, the work of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Kirill Medvedev, and Nobel Prize-winner Svetlana Alexievich's Voices from Chernobyl. A regular contributor to The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, and New York magazine, Gessen teaches journalism at Columbia and lives in New York with his wife, the novelist Emily Gould, and their two sons.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Author's Note

I wrote this book out of desperation.

For the first few months of my son Raffi's life, I felt like I was merely surviving. Through the sleeplessness and terror, I put one parenting foot in front of the other and tried not to look too far ahead. But when this passed, what I wanted, more than anything, was to talk. I had never before experienced such a contradictory mass of feelings; had never engaged in an activity so simultaneously mundane and significant; had never met anyone like screaming two-month-old Raffi, or cuddly one-year-old Raffi ("Uck," he would say, when he wanted a hug), or scourge of our household two-and-a-half-year-old Raffi. Through each of these phases I was amazed by his transformations, his progress, and my own complicated reactions. I wanted to know if other people were going through the same.

Parents talked, of course. My wife, Emily, and I talked all the time about Raffi, and we sought out other parents on the playgrounds, on street corners, even on the subway. Some of us, when we talked, couldn't help but brag. "He started sleeping through the night last week," someone might say, alienating their interlocutor forever. Or: "His grandparents took him for the weekend, and we slept late." (An active in-town grandparent was worth, by my informal calculations, about forty thousand dollars a year.) Others went in the other direction. Their child wouldn't nap; he threw his food onto the floor; he bit a kid in day care. Emily and I were in the self-deprecating camp. But of course this left out something too-the physical joy of being with Raffi, the hilarity of much of what he did. There was, in short, a limit to what you could get at when chatting with other parents. I felt like these conversations never went far enough.

There were books about parenting. Some of them were very good; most were not. In its main current, parenting literature was the literature of advice. The books diagnosed a sickness-your child's sleep "problem," your son's behavior "issue"-and promised to solve it. When the solution didn't work, you blamed yourself. Then you sought out another book, one that would "work" better, and went through the cycle again.

There was a particular gap, I thought, in the dad literature. In the few books out there, we were either stupid dad, who can't do anything right, or superdad, a self-proclaimed feminist and caretaker. I was sure those dads existed, but I didn't know any. The dads I knew took their parenting responsibilities seriously, were not idiots, and did their best around the house and with the kids. With some notable exceptions, they did less parenting than their spouses. Nonetheless, they thought it was one of the most important things they were going to do with their lives.

At the time I started working on this book, when Raffi had just turned three, I was supposed to be doing other things. I had a novel coming out that I needed to promote, and then a nonfiction book on U.S.-Russia relations that I should have been researching. But I couldn't stop thinking about Raffi: about our situation with him; about the situation of all parents with their little kids. I began taking notes and eventually I started writing these essays.

I felt ridiculous about it at times. To write about parenting when you are a father is like writing about literature when you can hardly read. Almost without exception, in every male-female relationship I encountered, the mothers knew more about their kids than the fathers and parented them better. My own relationship was no exception. My wife, the writer Emily Gould, was an extremely well-informed parent who also, not long after Raffi was born, started writing occasional essays about him. I love those essays as much as anything she has written. But there were things that I did with Raffi-talk Russian, play sports, yell in Russian-that were particular to my experience. And I came to think there was some value in recording my own groping toward knowledge in this most important of human endeavors, a kind of record of a primitive consciousness making its way toward the light. I was part of the first generation of men who, for various reasons, were spending more time with their kids than previous generations. That seemed notable to me.

I recently asked my own father if he remembered my second-grade teacher, Ms. Lynch, because I had just called her up to interview her about education. He said he didn't, and wouldn't. "But you must have gone to the parent-teacher conferences?" I said. "Oh no," said my dad. "I was at work." My father had relocated us halfway around the world so that we wouldn't have to grow up in the Soviet Union; drove me to every single hockey game I ever played in from the ages of six to sixteen, which was hundreds of hockey games; almost never traveled for work; and taught me math, physics, how to drive, and how to throw a left hook. He was hardly an absent father. But to him the idea of attending a parent-teacher conference was risible, whereas I consider the quarterly parent-teacher conferences for Raffi major events in my life.

This book consists of nine essays, arranged by subject: birth, zero to two, bilingualism, discipline, picture books, schools, the pandemic, sports, and cross-cultural parenting. Each of the essays describes my experience as a parent; draws on some of the literature and conversations I've found most helpful (or unhelpful) in thinking through this experience; and comes or doesn't come to a conclusion. I've tried to make it so that the essays can be read independently, if a busy parent doesn't have any interest in, for example, bilingualism; but I've also sought to avoid repetition and placed things in a more or less chronological way so that a reader going through the entire book can see Raffi (and me and his mother) slowly moving into the future.

Most of the material is from my personal experience, though as you'll see, one of the things I do to understand my experience is read. Where appropriate, I have also used my training as a journalist to talk with some of the people I thought would have the most to say on a given subject, whether it's the purpose of education, the nature of Russian parenting, or the lessons of parenting research in comparative perspective. I hope these conversations do not seem out of place; they were important to me in thinking through these issues.

I wrote some of these essays earlier than others, and in instances where I have changed my mind or learned a lot more about the subject-for example, by having another child and seeing him, at age three, suddenly turn from angel to avenger-I have tried to incorporate that later insight into the text. The thing I've learned about parenting, the thing that the parenting books don't tell you, is that time is the only solution. You do eventually figure it out, or start to. But by then it is often too late. The damage-to your child, yourself, your marriage-has already been done. That is the way of knowledge, though. In its purest form, it always comes too late.

Home Birth

I was not prepared to be a father-this much I knew. I didn't have a job and I lived in one of the most expensive cities on the planet. I had always assumed that I'd have kids, but I had spent zero minutes thinking about them. In short, though not young, I was stupid.

Emily told me she was pregnant when we were walking down Thirty-Fourth Street in Manhattan, on the way to Macy's to shop for wedding rings. Our wedding was a few weeks away, and I had, as usual, put off preparing until the last minute. I had a fellowship at the time at the New York Public Library in midtown, and I must have googled "wedding rings near me." Macy's it was. All around us on Thirty-Fourth Street people were shopping and hurrying and driving and honking. Emily told me, and I thought, "OK. Here we go. We are going to have a...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Suchergebnisse für Raising Raffi: The First Five Years

Raising Raffi: The First Five Years

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0593300440I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Raising Raffi: The First Five Years

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0593300440I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Raising Raffi: The First Five Years

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0593300440I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Raising Raffi: The First Five Years

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0593300440I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Raising Raffi : The First Five Years

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 40806101-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 3 verfügbar

Raising Raffi : The First Five Years

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 40803461-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Raising Raffi : The First Five Years

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 42286887-75

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 3 verfügbar

Raising Raffi : The First Five Years

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 42286887-75

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 4 verfügbar

Raising Raffi

Anbieter: Magers and Quinn Booksellers, Minneapolis, MN, USA

hardcover. Zustand: Like New. May have light shelf wear and/or a remainder mark. Complete. Clean pages. Artikel-Nr. 1347261

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Raising Raffi : The First Five Years

Anbieter: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Very Good. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 40803461-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar