Inhaltsangabe

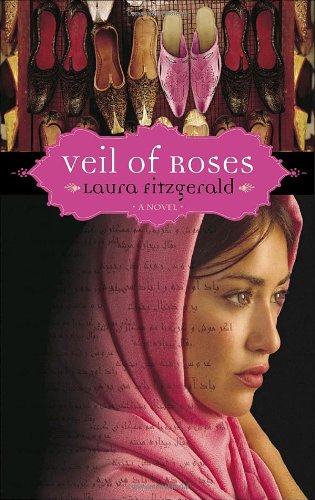

This compelling debut follows one spirited young woman from the confines of Iran to the intoxicating freedom of America-where she discovers not only an enticing new country but the roots of her own independence. . . .

Tamila Soroush wanted it all. But in the Islamic Republic of Iran, dreams are a dangerous thing for a girl. Knowing they can never come true, Tami abandons them. . . . Until her twenty-fifth birthday, when her parents give her a one-way ticket to America, hoping she will "go and wake up her luck." If they have their way, Tami will never return to Iran . . . which means she has three months to find a husband in America. Three months before she's sent back for good.

From her first Victoria's Secret bra to her first ride on a motor scooter to her first country line-dance, Tami drinks in the freedom of an American girl. Inspired to pursue her passion for photography, she even captures her adventures on film. But looming over her is the fact that she must find an Iranian-born husband before her visa expires. To complicate matters, her friendship with Ike, a young American man, has grown stronger. And it is becoming harder for Tami to ignore the forbidden feelings she has for him.

It's in her English as a second language classes that Tami finds a support system. With the encouragement of headstrong Eva, loyal Nadia, and Agata and Josef, who are carving out a love story of their own, perhaps Tami can keep dreaming-and find a way to stay in America.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Laura Fitzgerald lives in Tucson, Arizona with her Iranian-American husband and their two children.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Chapter One

As I walk past the playground on my way to downtown Tucson, I overhear two girls teasing a third: Jake and Ella sitting in a tree. K-I-S-S-I-N-G. First comes love, then comes marriage, then comes a baby in a baby carriage!

Curious, I stop mid-stride and turn my attention to Ella, the redheaded girl getting teased. She looks forward to falling in love; I can see it by the coyness in the smile on her freckled nine-year-old face. I shake my head in wonder, in openmouthed awe. I think, as I so often do: This would never happen in Iran.

None of it. Nine-year-old girls in Iran do not shout gleefully on playgrounds, in public view of passersby. They do not draw attention to themselves; they do not go to school with boys. They do not swing their long red hair and expect with Ella's certainty that romantic love is in their future. And they do not, not, not sing of sitting in trees with boys, kissing, and producing babies. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, there is nothing innocent about a moment such as this.

And so I quickly lift the Pentax K1000 that hangs from my neck and snap a series of pictures. This is what I hope to capture with my long-range lens: Front teeth only half grown in. Ponytails. Bony knees. Plaid skirts, short plaid skirts. That neon-pink Band-Aid on Ella's bare arm. I blur out the boys in the background and keep my focus only on these girls and the way their white socks fold down to their ankles. The easiness of their smiles. They are so unburdened, these girls, so fortunate as to take their good fortune for granted.

Ella sees me taking pictures and nudges the others, so I lower my camera, wave to them, and give them my biggest, best pretty-lady smile, one I know from experience causes people to smile back. And sure enough, they do. I wave one last time and then I walk on. I am changed already, from just this little moment. These fearless girls have entranced me, and I know that when I study my photographs of these recess girls, I will look for clues as to what sort of women they will become.

I hope they find romantic love. And passionate kisses, and men who look at them with eyes that see all the way into their souls. Then I know they will be happy, and I know they will be whole.

First comes love, then comes marriage. A childhood chant, a cultural expectation. Americans believe in falling in love with every fiber of their being. They believe it is their birthright; certainly, that it is a prerequisite for marriage. This is not so where I was raised. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, marriages are often still negotiated between families with a somewhat businesslike quality. In most modern families, girls have some say in the matter. They can discourage suitors, or, as I did, delay marriage by seeking a university degree.

It isn't that Iranian men necessarily make bad husbands. Like my dear father, many are kind and gentle and interested in their wives as people, not just bearers of their children. Then again, some are not. There are family teas, gift-givings, and dinners, but a woman often spends no time alone with her fiancé before her wedding. So it is, as one might say in America, a crapshoot. A woman goes into her husband's family in a white gown and she leaves it only in a white shroud, in death.

That is our culture.

And that is our future, inescapable for most girls.

Inescapable, it had begun to seem, even for me.

On the occasion of my twenty-seventh birthday, my parents hosted a celebration dinner for me in their fine north Tehran apartment. We typically do not celebrate birthdays in a large fashion, but it had been a troublesome time for me and they hoped to bring me happiness. In only my fourth year of teaching, I'd recently resigned my position, against the advice of my parents. And this after I'd dreamed so long of being a teacher, a teacher of young girls. Increasingly since I'd begun, I suffered sta

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Suchergebnisse für Veil of Roses

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. L11A-02603

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 4 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0553383884I2N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0553383884I2N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 6380380-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. GOR006632189

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: AwesomeBooks, Wallingford, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Veil of Roses This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Artikel-Nr. 7719-9780553383881

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. Ships from the UK. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. GRP57891899

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: Bahamut Media, Reading, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Artikel-Nr. 6545-9780553383881

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: Robinson Street Books, IOBA, Binghamton, NY, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Prompt Shipment, shipped in Boxes, Tracking PROVIDEDVery good trade paperback. Clean pages. Minor creasing. Artikel-Nr. boiler41mm026

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Veil of Roses

Anbieter: Robinson Street Books, IOBA, Binghamton, NY, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Prompt Shipment, shipped in Boxes, Tracking PROVIDEDVery good, Some Creasing. Artikel-Nr. ware345mh778

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar