Verwandte Artikel zu And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed...

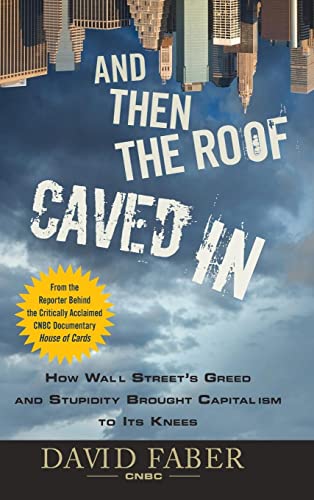

And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees - Hardcover

Inhaltsangabe

CNBC's David Faber takes an in-depth look at the causes and consequences of the recent financial collapse

And Then the Roof Caved In lays bare the truth of the credit crisis, whose defining emotion at every turn has been greed, and whose defining failure is the complicity of the U.S. government in letting that greed rule the day. Written by CNBC's David Faber, this book painstakingly details the truth of what really happened with compelling characters who offer their first-hand accounts of what they did and why they did it.

Page by page, Faber explains the events of the previous seven years that planted the seeds for the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. He begins in 2001, when the Federal Reserve embarked on an unprecedented effort to help the economy recover from the attacks of 9/11 by sending interest rates to all time lows. Faber also gives you an up-close look at where the crisis was incubated and unleashed upon the world-Wall Street-and introduces you to insiders from investment banks and mortgage lenders to ratings agencies, that unwittingly conspired to insure lending standards were abandoned in the head long rush for profits.

- Based on two years of research, this book provides deep background into the current credit crisis

- Offers the insights of experienced professionals-from Alan Greenspan to prominent bankers and regulators-who were on the front lines

- Created by David Faber, the face of morning business news on CNBC, and host of the network's award winning documentaries

From regulators who tried to stop this problem before it swung out of control to hedge fund managers who correctly foresaw the coming housing crash and profited from it, And Then the Roof Caved In shows you how the crisis we currently face came to be.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

DAVID FABER, an Emmy, Peabody, and duPont Award winner, is the anchor and coproducer of CNBC’s acclaimed original documentaries and long-form programming as well as a contributor to CNBC’s Squawk on the Street. He has been reporting on Wall Street and corporate America for over twenty-two years, sixteen of them as the foremost reporter at CNBC. Faber has broken numerous stories including the massive fraud at WorldCom and News Corp.’s hostile bid for Dow Jones. He was a founding member of CNBC’s signature morning show, Squawk Box. Faber also blogs at FaberReport.cnbc.com.

Von der hinteren Coverseite

CNBC's David Faber unmasks the truth behind the economic crisis, whose defining theme at every turn has been greed. Greed that, when coupled with the regulatory failure of the U.S. government, was allowed to rule the day.

And Then the Roof Caved In painstakingly details what really happened to cause the greatest economic collapse since the Great Depression. Written by David Faber&;the award-winning correspondent who has covered Wall Street for more than two decades&;this compelling story is filled with the firsthand accounts of the bankers and regulators who unleashed this crisis on the world. They tell Faber what they did and why they did it.

Faber traces the lineage of the subprime industry and takes you back to the attacks of 9/11, after which Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan embarked on an unprecedented effort to help the economy recover by sending interest rates to all-time lows. Faber details the precipitous drop in lending standards, which allowed people with marginal incomes to take on mortgages they could not afford, and explains how those mortgages came back to wreck the financial system.

And Then the Roof Caved In also reveals where this crisis was incubated&;Wall Street&;and introduces you to insiders from investment banks and mortgage lenders who fostered the boom and, in doing so, planted the seeds for such an astonishing economic collapse. Throughout the book, Faber weaves a narrative that takes you from subprime lenders like Quick Loan Funding and big investment banks like Merrill Lynch to regulators who tried to stop the crisis before it spiraled out of control and hedge fund managers who correctly foresaw the coming housing crash and profited from it.

Engaging and informative, And Then the Roof Caved In offers a definitive, up-close and personal analysis of the roots of this stunning worldwide economic failure.

Aus dem Klappentext

And Then the Roof Caved In painstakingly details what really happened to cause the greatest economic collapse since the Great Depression. Written by David Faber--the award-winning correspondent who has covered Wall Street for more than two decades--this compelling story is filled with the firsthand accounts of the bankers and regulators who unleashed this crisis on the world. They tell Faber what they did and why they did it.

Faber traces the lineage of the subprime industry and takes you back to the attacks of 9/11, after which Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan embarked on an unprecedented effort to help the economy recover by sending interest rates to all-time lows. Faber details the precipitous drop in lending standards, which allowed people with marginal incomes to take on mortgages they could not afford, and explains how those mortgages came back to wreck the financial system.

And Then the Roof Caved In also reveals where this crisis was incubated--Wall Street--and introduces you to insiders from investment banks and mortgage lenders who fostered the boom and, in doing so, planted the seeds for such an astonishing economic collapse. Throughout the book, Faber weaves a narrative that takes you from subprime lenders like Quick Loan Funding and big investment banks like Merrill Lynch to regulators who tried to stop the crisis before it spiraled out of control and hedge fund managers who correctly foresaw the coming housing crash and profited from it.

Engaging and informative, And Then the Roof Caved In offers a definitive, up-close and personal analysis of the roots of this stunning worldwide economic failure.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

And Then the Roof Caved In

By David FaberJohn Wiley & Sons

Copyright © 2009 David FaberAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-470-47423-5

Chapter One

Bubble to Bubble

On the morning of September 12, 2001, Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Federal Reserve, was hurriedly returning from overseas. No planes were flying into the United States that day, other than his. Before landing in Washington, D.C., Greenspan asked the pilot to fl y over the felled towers of the World Trade Center in downtown New York City. As Greenspan viewed the devastation from above, he was deeply concerned about the U.S. economy. Greenspan's overriding fear was that it would simply cease to function. "History has told us that this kind of a shock to an economy tends to unwind it. Because remember, economies are people meeting with each other. And you had nobody engaging in anything. I was very much concerned we were in the throes of something we had never seen before," recalls Greenspan.

When those planes hit the towers, the U.S. was already in a recession. It was a mild recession, to be sure, but a recession all the same. The United States was suffering from the deflation of one of the greatest speculative bubbles our markets had ever seen. It was quite a party while it lasted. Hundreds of billions of dollars had been thrown at technology companies of all kinds in a frenzy that defied all logic and all the tenets of prudent investing. Few thought we would ever see a bubble of its kind again.

The technology bubble was very kind to CNBC. Our ratings were routinely above those of any other cable news network and almost all of our viewers, save those who were short the market, were in a good mood. Each day brought a new high in the NASDAQ, and with each year the suspension of disbelief grew. The years 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2000 were some of the greatest Wall Street has ever experienced. There was a new paradigm in town. Earnings were of little import. The Internet and anything related to it were all a company needed to be focused on to generate enthusiasm. Growth in revenues, regardless of whether that growth came at the expense of actual earnings, was the only thing investors seemed to care about.

The world was awash in capital, which could be raised in copious amounts for even the worst of businesses. This wasn't a bubble, they scolded the nonbelievers, it was a new age. Naysayers were dismissed as "not getting it." I will not rehash all the high points of the great technology bubble of the late 1990s, but for the sake of capturing the flavor of the times, I'll relate some of the more amazing tech-bubble facts.

In January 1999, Yahoo! was valued at 150 years' worth of its expected annual revenues for that year. At that same moment, Yahoo!'s value was equal to 693 years' worth of its expected 1999 earnings. The point is that if Yahoo!'s earnings were to stay the same, it would take 693 years for those earnings to equal what one had spent to buy the stock. That is not really a great value. And Yahoo!, despite being one of the few companies to truly succeed in the Internet era, now trades at 25 times its expected earnings-far below the value it commanded in 1999.

One of the highest-valued mergers of all time involved two companies few people had ever heard of then and most have certainly forgotten by now, JDS Uniphase Corporation and SDL. When JDS Uniphase agreed to buy SDL in July 2000, the deal was valued at $41 billion. The two companies made things that helped fiber-optic networks operate more efficiently, and that was largely the extent of what anyone knew about these companies. JDS Uniphase still exists today. Its stock trades below $5 a share, valuing the company at around $600 million.

Everyone, and I mean everyone, seemed to be playing the stock market. Early one morning in the summer of 1998, I parked my car in a spot that blocked a fruit vendor from pulling his cart to his chosen location. The vendor approached my driver's-side window and upon seeing me immediately started singing the praises of CNBC. It seems he sold fruit from his pushcart in the mornings and then returned home to trade stocks for the remainder of the market day. To me, that is the very definition of a bubble.

When it burst, it took a whole lot of money with it and quite a few jobs, as hundreds of dot-com and telecom companies were forced to close their doors when the free flow of capital abruptly ended. By the end of 2000, according to the search firm of Challenger, Gray and Christmas, dot-com companies were cutting jobs at a rate of 11,000 a month. The NASDAQ, which peaked in March 2000 at 5000, fell more than 3,000 points over the next year. With job losses mounting and wealth vanishing, the growth of the economy slowed dramatically through 2000 and stopped entirely by the middle of 2001. And then came 9/11.

Greenspan's Shock and Awe

Alan Greenspan was chairman of the Federal Reserve from August 1987 through February 2006. He was the longest-serving Fed chairman in history, and, until recently, widely regarded as one of the greatest Fed chairmen our country has ever had. He has been endlessly praised for helping to shepherd the economy through the countless shocks it was dealt during his tenure-from the 1987 stock market crash to the collapse of the savings and loan industry in the early 1990s to the implosion of the hedge fund Long Term Capital in 1998 to the horror of 9/11.

Dr. Greenspan's well-worn face shows every one of his 82 years. But he is still sharp of mind and wit. Since the financial crisis hit, Greenspan's legacy has been tarnished. That's one reason why he graciously gave of his time during a September morning in 2008 when I interviewed him at the Mayflower hotel in Washington, D.C.

His celebrity is such that immediately after our interview, his half-eaten bran muffin became a source of focus for our camera crew and my producer, James Jacoby. Our lead cameraman, Marco Mastrorilli, suggested we bag the Greenspan muffin and list it on eBay. Authentication would be relatively easy, since we likely had some film of the man taking a few bites. My producer, however, claimed his father was a great fan of the good doctor Greenspan and asked if he could deliver the muffin to his dad as a gift. We decided that was a worthy home for the Greenspan muffin.

Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, like every Fed chairman before and since, played the decisive role in figuring out where interest rates in the United States should be set. Whereas investors in the U.S. government bond market can certainly influence longer term interest rates, they take their cue from the short-term rates controlled by the Federal Reserve.

As the bubble in technology stocks inflated, Alan Greenspan kept interest rates in a tight range of between 5 and 6 percent. A couple of months after the NASDAQ peaked in March 2000, rates were raised to 6.5 percent. To put this in perspective, 6.5 percent is a higher rate than we have seen for quite some time, but well below the mid-teens levels at which interest rates hovered in the late 1970s.

It wasn't until the start of 2001 that Greenspan and his Fed governors, seeing a slowdown in the economy, started to lower interest rates. Fed Funds were 6 percent at the beginning of 2001 and, due to seven separate cuts in interest rates, had fallen to 3.5 percent by August of that year. "We did not start cutting rates, in spite of the sharp contraction in the financial system starting in the summer of 2000, until we were sure the dot-com bubble had sufficiently diffused," Greenspan explains.

On the day after the World Trade Center attacks, Greenspan's decision to view the devastation in lower Manhattan was not only about economics, but also about understanding what damage had been done to the payments system relied on by financial companies around the world. Much of the structural backbone of payments resided in lower Manhattan. When a stock was sold, or a bond was bought, or a check was cleared, the processing of those transactions often took place at institutions that were housed in lower Manhattan. And in a true stroke of stupidity, many of the computer systems that backed up those transactions were also housed in lower Manhattan. "There were several institutions which were in serious trouble because their redundancies went down with their primary systems because it was all too close to the World Trade Center," explains the former Fed chairman.

The Fed's first order of business on September 12 was to lend billions of dollars to banks in order to maintain liquidity in the system given the structural breakdowns that had taken place. It was only after the Fed had made sure the process of intermediation for financial transactions would continue to function that it could then focus on what the attacks of 9/11 would mean for the U.S. economy.

Given Greenspan's fear of an economic collapse, it is not a surprise that he aggressively reduced interest rates. The first cut came six days after the attacks bringing the Federal Funds rate to 3 percent. Two weeks later, Greenspan would send rates down another one-half of a percent to 2.5 percent. President George W. Bush went on television exhorting the American people to help keep the economy afloat and go out and shop. The rate cuts kept coming. November 6 saw another one-half percent reduction in interest rates, and the following month Greenspan engineered yet another cut, this time one-quarter of a percent. (See Table 1.1.)

In the space of three months, interest rates were cut in half. Borrowing costs for corporations and consumers had plummeted to a level not seen in almost 50 years. And that cheap money was starting to have its intended effect. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) had fallen sharply in the six weeks that followed the terrorist attacks. But then things began to stabilize. Consumers, whose spending represented 70 percent of the country's economic output, began to spend again.

Long before he became Fed chairman, Alan Greenspan, as a noted economist, had traced the early versions of an important trend he called "mortgage equity withdrawal." In the early 1980s, Greenspan found that when a home was sold, the seller was typically canceling a mortgage that was much smaller than the purchase price of the home. This fact created two outcomes. The person who had sold the home usually increased his personal consumption, meaning he bought more stuff, and the home that was bought from him now had a bigger mortgage on it. Essentially, while the home had changed owners, debt was replacing equity in the home and the cash that was freed up found its way into the cash registers of businesses. Indeed, as a government economist, Greenspan used his "mortgage equity withdrawal" metric to forecast the future sales of cars and other hard goods.

In early 2002, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan was still following his much-loved indicator of mortgage equity withdrawal, and what he saw gave him some relief that an economic catastrophe had been averted. Unlike the 1980s, when a home was most often sold in order to unlock the equity in it and free it up for spending, by 2002 a vast industry with myriad mortgage products had sprung up, which allowed people to stay in their homes and withdraw equity from them. This is known as the home equity loan. That loan is essentially a second mortgage in which the debt is backed by the collateral in the home that exceeds the homeowner's first mortgage. While home equity loans had existed for many years, their use became far more widespread during this period because as interest rates fell to historic lows, people could avail themselves of home equity lines of credit at very cheap rates.

But there was another more important trend that was also brought on by the fall in interest rates. People were starting to refinance their mortgages in record numbers. Some people chose to keep their mortgages the same size and simply lower their monthly payments. But many others saw an opportunity to capture equity that had built up in their homes by increasing the size of their mortgage. Because their interest rate would be lower, their monthly payment might not rise at all, while they would find themselves with a slug of cash they could spend on a new car, a new kitchen, a new mink coat, or all three. It was called the cash-out refinancing and it would play a prominent role in the collapse that would come six years later.

Greenspan and his cohorts at the Fed quickly noticed the uptick in consumer spending. "You began to see a combination of the personal savings rate declining and mortgage equity extraction rising. And indeed, from a bookkeeping point of view, it was the rising debt that was subtracting from savings. And you could begin to see the impact of that spilling over into consumer markets." Greenspan says it was never the intent of the Fed to galvanize the housing market, but he admits the Fed welcomed the increase in consumer spending. The cuts in interest rates had worked. The increase in consumer spending staved off an economic calamity and was helping to bring the United States out of recession.

The Fed's intent may not have been to galvanize the housing market, but that is exactly what happened. That market, made up of homebuyers, home builders, and the firms that provide them credit, loved low interest rates. While the Fed Funds rate did not dictate the price of a mortgage, which is more closely linked to the rate on a 10-year Treasury bond, it did have a pronounced effect on the price of that 10-year bond. And the Fed kept pushing rates lower; 1.75 percent became 1 percent by June 2003, and Greenspan's Fed kept the Funds rate at 1 percent for a year after that. Our country had never really known 1 percent interest rates. While mortgage rates were nowhere near that level, they were at all-time historic lows.

In 2003, a 30-year mortgage came at an average interest rate of 5.83 percent after having averaged 8.05 percent only three years earlier when interest rates were far higher. In 2004, the average interest rate for the 30-year mortgage was 5.84 percent and in 2005 it was 5.87 percent. The rates for one- and five-year adjustable rate mortgages were also at never-before-seen lows. For example, a one-year adjustable rate mortgage could be secured with an average interest rate of 3.76 percent in 2003. Lower mortgage rates translated into lower monthly payments and that helped make owning a home affordable for many people who had never before contemplated it.

Unbeknown to Greenspan, his interest rate cuts had unleashed an engine of commerce the likes of which our country had never seen. It was an engine fueled by cheap money that would bring the greatest housing boom in history and then devour all it had created and more.

Houses Built on Cow Dung

In 2003, in the Eastvale section of the Southern California town of Corona, Joseph Dunkley, a chiropractor, and his wife, Barbara, a real estate agent, bought a home for a little over $ 300,000 in a field full of cow dung. The Dunkleys' new home had been built in a field where dairy cows had grazed for decades until the dairymen sold out and moved to central and northern California. The land they left behind smelled terrible. Decades of cow crap will do that to a place. But the Dunkleys and plenty of people like them jumped at the chance to live the American Dream, even if it came with a nasty odor.

The homes built in Eastvale, part of the so-called "Inland Empire," were relatively inexpensive for Southern California and a good deal larger than a home one might find in Orange or Los Angeles county. The developers were building a sleeper city, filled with commuters who spent their day working in Los Angeles, but traveled 90 minutes on the choked 91 freeway to spend their nights in their new homes. The Dunkleys were pioneers. "When we moved in I always said you had to have a vision to live here, because there was nothing here. No supermarkets. No retail shopping. Nothing but a lot of cows. And they were just starting to pop up these developments and the people who were developing it were saying 'this is going to be a nice area,'" explains Barbara.

The Dunkleys were undeterred by the commute and the smell and the lack of any real neighborhood. "We had our names on quite a few waiting lists just wanting to buy," said Barbara Dunkley. It took the Dunkleys four months before they had the chance to make a down payment on a home. They did so without even touring a model. "It was so crazy. The lines were huge on the days they would release maybe 15 houses-you'd have fifty to one hundred people in line trying to scoop up the properties," she explained.

The Dunkleys bought their house in January 2003 and moved in that June. In the intervening six months, the value of their house had increased from $300,000 to $400,000, adding $100,000 to their equity before they even pulled into the driveway. The Dunkleys' home was in the first tract of houses to be put up in the new development and all of their neighbors were feeling pretty good. So was Barbara Dunkley. "There was a huge excitement level. People were giddy and we all looked really smart."

(Continues...)

Excerpted from And Then the Roof Caved Inby David Faber Copyright © 2009 by David Faber. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

EUR 4,01 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenGratis für den Versand innerhalb von/der Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed...

And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Hardback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. GOR004901765

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Fair. 1. The item might be beaten up but readable. May contain markings or highlighting, as well as stains, bent corners, or any other major defect, but the text is not obscured in any way. Artikel-Nr. 0470474238-7-1

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In : How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. GRP76998394

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In : How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. GRP76998394

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.9. Artikel-Nr. G0470474238I2N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.9. Artikel-Nr. G0470474238I2N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees

Anbieter: Bahamut Media, Reading, Vereinigtes Königreich

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Artikel-Nr. 6545-9780470474235

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees

Anbieter: AwesomeBooks, Wallingford, Vereinigtes Königreich

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Artikel-Nr. 7719-9780470474235

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Gebunden. Zustand: New. David Faber is known as one of the cooler heads on financial news channel CNBC. True to his reputation, calm prevails through most of the book. Faber explains rather than rants about these mortgages, as well as securitizations and bogus credit ratings,. Artikel-Nr. 556555664

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

And Then the Roof Caved In: How Wall Street's Greed and Stupidity Brought Capitalism to Its Knees

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. D14A-02499

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar