Inhaltsangabe

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

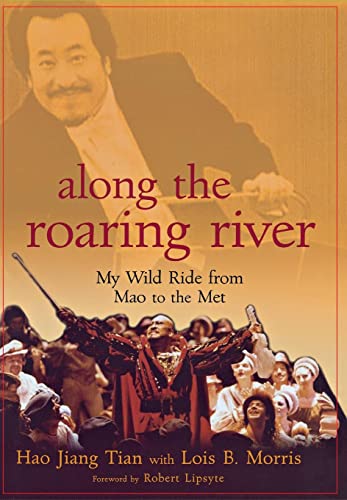

Hao Jiang Tian is the first Chinese-born opera singer to achieve a lasting success on world stages. A bass with a voice that is unusually sweet and versatile, he has appeared at the Metropolitan Opera every season since he debuted there in 1991. He performs the major bass roles at the great opera houses around the globe. Recently he and his wife, Martha Liao, have begun to foster new Chinese opera and talent for the world to hear. Now an American citizen, Tian has homes in New York City, Denver (where he used to sing at a piano bar), and Beijing.

Lois B. Morris and her husband, Robert Lipsyte, have written for the New York Times about classical music and opera. Separately, Morris writes about mental health and psychology, including a long running column in Allure. She has written or co-written eight books. Lipsyte is a New York Times contributor, former sports and city columnist, and television commentator. He has written seventeen books.

Von der hinteren Coverseite

Since his 1991 debut at New York's Metropolitan Opera, Hao Jiang Tian has appeared on the world's greatest stages, more than 300 times at the Met alone. How he got there, how-ever, is a drama of bittersweet humor, mortal danger, heartbreaking tragedy, and inspiring triumph?more passionate and turbulent than even the grandest opera.

In Along the Roaring River, Tian relives his coming of age in China during one of its most chaotic periods, the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. Wild and rebellious, nature-loving, emotional, and yearning for beauty, he finds release in underground love songs howled from mountaintops and banned books stolen from boarded-up libraries. Dec-ades after leaving China during the post-MaoAnti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign, he returnsto find his homeland vastly different. Inbetween, more by fate than by design, heachieves success in the most Western of art forms?and takes his place among the influential Chinese artists, film directors, and composers of this era, who were all shaped by that terrible time.

Tian was born to stern revolutionary parents who became important musicians in the People's Liberation Army, enjoying the privileges reserved for officials of New China. The boy showed little promise of living up to his parents' expectations. He hated music. He celebrated the end of his forced lessons at the piano?the "big black beast with eighty-eight teeth"?when his unsmiling teacher was sentenced to isolation for counterrevolutionary tendencies. Then, when Tian's own loyal Communist parents were sent to a far-off coal-mining town to be "reeducated," young Tian found himself abandoned and alone in Beijing. Without parental supervision, outside politics, and, at age fifteen, assigned to hard labor?cutting metal in the Beijing Boiler Factory?the young man found himself spiritually free. He even fell in love with the piano-beast, with which he shared his tiny, lonely room. He taught himself accordion and that most decadent of instruments, the guitar. He became a singer by chance, and, after seven years, tricked his way out of the factory and into a musical audition that changed his life. He smuggled watches with gun-wielding gangsters to scrape together enough money to leave China. And then, on his way to Denver to study voice, on his first day in the United States, he went to the Metropolitan Opera and saw the very first opera of his life. Eight years later, he made his debut at the Met alongside Plácido Domingo.

Peppered with charming, frightening, and sobering anecdotes, Along the Roaring River is important and rewarding reading for anyone who loves opera, political history, or a thrilling and powerful true story well told.

Aus dem Klappentext

Since his 1991 debut at New York's Metropolitan Opera, Hao Jiang Tian has appeared on the world's greatest stages, more than 300 times at the Met alone. How he got there, how-ever, is a drama of bittersweet humor, mortal danger, heartbreaking tragedy, and inspiring triumph?more passionate and turbulent than even the grandest opera.

In Along the Roaring River, Tian relives his coming of age in China during one of its most chaotic periods, the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. Wild and rebellious, nature-loving, emotional, and yearning for beauty, he finds release in underground love songs howled from mountaintops and banned books stolen from boarded-up libraries. Dec-ades after leaving China during the post-MaoAnti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign, he returnsto find his homeland vastly different. Inbetween, more by fate than by design, heachieves success in the most Western of art forms?and takes his place among the influential Chinese artists, film directors, and composers of this era, who were all shaped by that terrible time.

Tian was born to stern revolutionary parents who became important musicians in the People's Liberation Army, enjoying the privileges reserved for officials of New China. The boy showed little promise of living up to his parents' expectations. He hated music. He celebrated the end of his forced lessons at the piano?the "big black beast with eighty-eight teeth"?when his unsmiling teacher was sentenced to isolation for counterrevolutionary tendencies. Then, when Tian's own loyal Communist parents were sent to a far-off coal-mining town to be "reeducated," young Tian found himself abandoned and alone in Beijing. Without parental supervision, outside politics, and, at age fifteen, assigned to hard labor?cutting metal in the Beijing Boiler Factory?the young man found himself spiritually free. He even fell in love with the piano-beast, with which he shared his tiny, lonely room. He taught himself accordion and that most decadent of instruments, the guitar. He became a singer by chance, and, after seven years, tricked his way out of the factory and into a musical audition that changed his life. He smuggled watches with gun-wielding gangsters to scrape together enough money to leave China. And then, on his way to Denver to study voice, on his first day in the United States, he went to the Metropolitan Opera and saw the very first opera of his life. Eight years later, he made his debut at the Met alongside Plácido Domingo.

Peppered with charming, frightening, and sobering anecdotes, Along the Roaring River is important and rewarding reading for anyone who loves opera, political history, or a thrilling and powerful true story well told.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Along the Roaring River

My Wild Ride from Mao to the MetBy Hao Jiang Tian Robert Lipsyte Lois B. MorrisJohn Wiley & Sons

Copyright © 2008 Hao Jiang TianAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-470-05641-7

Chapter One

Music Torture

The mood in the Metropolitan Opera rehearsal room was tense and frustrated. Tempers were fraying.

"I can't play it another way. I've changed it so many times already, I just cannot do it again," said the normally accommodating soprano Elizabeth Futral, in a don't-mess-with-me tone of voice.

The December 2006 world premiere of The First Emperor was one week away, and our collective spirit was deteriorating. Every opening of a new production is fraught; multiply that by a hundred for a brand-new opera. But this opera had even more at stake. Plcido Domingo, the biggest star currently on the opera stage, was heading this first-ever Chinese-written, Chinese-directed, Chinese-designed opera, which was also the first-ever collaboration between the Metropolitan Opera and a Chinese creative team. Composer Tan Dun, whose film scores for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero were his works most familiar to American audiences, had teamed with Chinese film director Zhang Yimou, whose movies had ranged from the small and tragic, such as Raise the Red Lantern, to the spectacular, like Hero. The libretto was written in English by the prize-winning Chinese novelist Ha Jin.

For me, The First Emperor represented the first time in my opera career that I would sing the role of an actual Chinese character in a work about real Chinese history. By that time, I had sung King Timur in Puccini's Italian conception of a Chinese opera, Turandot, at least two hundred times in opera houses all over the world. But never had an opera been presented for Western ears that told an authentic Chinese story, written by a Chinese composer, with a production designed by a Chinese artist. I could bring my personal history and that of my country to bear on this work, in which I was to sing the principal role of the doomed General Wang, who also happens to have some great singing in this opera.

Publicity was everywhere in print and on the airwaves and had been growing for months. Now this opera was being billed as a breakthrough in the history of the art form and even of East-West relations. Oh, the pressure.

"Okay, let's take a twenty-minute break," sighed one of the Met's artistic staff members.

As the cast and production crew began to wander off, I sat down to let my fingers loose on the piano. I needed to lighten the mood. The tune that came to my fingers was "The East Is Red," the omnipresent anthem from the long-gone era of the Cultural Revolution. And then, all around me, one by one, Chinese voices began to sing:

Dongfan hong, taiyang sheng, Zhongguo chu liao ge Mao Zedong, Ta wei renmin mou xingu, Hu er hei you, ta shi renmin da jiu xing.

Our peals of laughter must have rolled out like a tidal wave into the hallway. The people from the Met and the non-Chinese performers, who had no idea what we were singing about, rushed back in. They were astonished to find Zhang Yimou, normally so dour, singing and raising his fist to the sky in a gesture familiar to anyone who had been alive during the Cultural Revolution. And his codirector, Wang Chaoge, who had been the most stressed out of his team, was actually dancing! Now all the singers were back in the room, and everybody was laughing, something no one had expected to experience during this rehearsal.

For the full twenty minutes we sang and sang and sang, one revolutionary song after another, plus set pieces with characteristic poses from the model operas we'd been required to attend during the Cultural Revolution. Wang Chaoge danced on, Zhang Yimou leaped about and gestured, and, as I added my own voice, I felt a rush of mixed feelings. The Cultural Revolution had been such a difficult time.

Whenever I sing "The East Is Red" now, so often I think back to an evening I spent in 1971 with a peasant farmer near my home in Beijing. The dumpling restaurant where I'd come for a cheap dinner that cold winter night was fairly crowded. I sat down at a table that had only one other customer, a very dirty man with a filthy old winter coat but no shirt on underneath. He probably wasn't as ancient as he looked, but the lines on his face were deep, not to mention dirt-caked. He quietly sang some old folk songs while nursing a cup of cheap Mongolian wine made from white yams. I'd heard many of his tunes before, since most of our revolutionary songs, including "The East Is Red," had been set to old folk melodies, but I'd never heard these lyrics, some of which were very romantic, some raunchy. Though it was a little hard to understand the man, because he had no front teeth, I got to talking with him. He told me he had just delivered a load of cabbages to the city and was now on the way back to his village. With his horse and cart, the trip in had taken him all day, and the trip back would take him all night. Because of traffic congestion, farmers with carts were allowed to come into the city only at night in those days. I asked him about his life and his songs, and for four hours I bought us both more cups of the harsh, burning, definitely intoxicating wine.

The man told me he knew all the old folk songs but wasn't so good at the new words. Back in 1966, he said, some Red Guards took offense when they heard him singing "The East Is Red" with the lyrics to the original love song. They rushed over and began to beat him. He was a counterrevolutionary, they yelled, because he had "changed the text" of an important revolutionary song, and that was a big crime. When they demanded that he sing it with the "correct" words, he was so scared he couldn't remember them. They beat him harder and threatened him more. At one point they had his head pushed down nearly to the ground as they hit him across the back of his skull. But the more they hurt him, the less he could recall the required lyrics. So they said that if he couldn't sing the song correctly, they would make sure he could no longer sing the words at all, and they smashed him with a stick directly in his mouth. Laughing as he told me this, he pointed to the empty hole where his front teeth should be. He laughed and laughed.

And here, more than thirty-five years later, in a rehearsal room at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, were three survivors of that horrific decade, singing those songs of oppression, yet suffused with the warmth of bittersweet nostalgia. We were back in our youth, the youth in our hearts, feeling a camaraderie that lifted our transient worldly cares. I felt such a loving kinship with my Chinese colleagues. We had come through that terrible time, yet in spite of it, or perhaps because of it, we had discovered our artistic identities. And life goes on.

We wrapped up our little intermezzo in such fine spirits, with a rendition of "East Wind Blows," a popular revolutionary song from those days with lyrics from a Chairman Mao quotation: "The east wind of socialism is prevailing over the west wind of imperialism." We sang it in Chinese, so who knew? We were young again, invigorated, ready for anything.

It was good to be born in Beijing.

Ever since the Forbidden City had become home to China's ruling dynasties in the fifteenth century, the people of Beijing have believed themselves more cultured, more refined, more knowledgeable, and better-spoken than everyone...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Suchergebnisse für Along the Roaring River: My Wild Ride from Mao to the...

Along the Roaring River : My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 8694778-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River : My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 3295283-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River : My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. 1st Edition. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 9999352-75

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River : My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 3295283-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River: My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. 1. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Artikel-Nr. 047005641X-11-1

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River: My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G047005641XI4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River : My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Very Good. 1st Edition. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 9999352-75

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River: My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: Mozart Books Ltd., Pasadena, CA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: Very Good. 1st Edition. Hardback. INSCRIBED by both artist Hao Jaing Tian (Chinese & English) and collaborator Lois B. Morris (with initials). Signed by Author(s). Artikel-Nr. 000433

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River: My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Signed Copy . Very Good dust jacket. Signed/Inscribed by author Tian on front endpage. Artikel-Nr. SB10M-00120

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Along the Roaring River: My Wild Ride from Mao to the Met

Anbieter: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. Signed. Signed by author!. Artikel-Nr. mon0003973276

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar