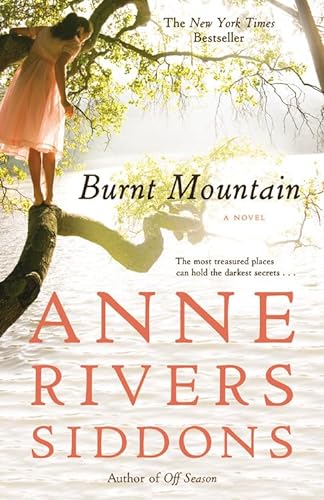

Inhaltsangabe

Growing up, the only place tomboy Thayer Wentworth felt at home was at her summer camp - Camp Sherwood Forest in the North Carolina Mountains. It was there that she came alive and where she met Nick Abrams, her first love...and first heartbreak. Years later, Thayer marries Aengus, an Irish professor, and they move into her deceased grandmother's house in Atlanta, only miles from Camp Edgewood on Burnt Mountain where her father died years ago in a car accident. There, Aengus and Thayer lead quiet and happy lives until Aengus is invited up to the camp to tell old Irish tales to the campers. As Aengus spends less time at home and becomes more distant, Thayer must confront dark secrets-about her mother, her first love, and, most devastating of all, her husband.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Burnt Mountain

By Anne Rivers SiddonsGrand Central Publishing

Copyright © 2012 Anne Rivers SiddonsAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780446698306

Prologue

We heard it first on an early morning in June. I thought then that it might have been going on for many mornings, but given what we know about it now, I realize that this must have been one of the first times that it sounded, perhaps the very first. This year, anyway.

It wafted into our bedroom on a soft green wind, along with the sleepy twitter of songbirds and the heartbreaking sweetness of wild honeysuckle from the woods behind the house. We had had one of Atlanta’s not-infrequent and unadvertised long, cold springs and had only slept with our windows open for the past month.

We had moved into our house just recently, and the sounds and smells of our new neighborhood were still unfamiliar to us, exotic in their strangeness. But we were learning. The sleep-murdering a.m. roar down the street had become the Suttles’ scowling teenage son starting his motorcycle; the choking miasma that often drifted over the lower end of the street was old Mr. Christian Wells, who had a widely known fear of West Nile virus, spraying his extensive lawn with a virulent pesticide; the shrill shriek that set every dog on Bell’s Ferry Road barking was Isobel Emmett across the street, who had forgotten once again that she had armed the house alarm.

This morning’s sound was different, though. This was the sound of children, many children, far away. Singing.

I lay for a moment without opening my eyes, trying to see if the sound tasted of dreams. It didn’t; the singing children seemed to be coming nearer, from somewhere in the west, and their song grew louder. I could almost make it out. It was a raucous shouted noise, somehow a summer song. I felt that. I knew it.

I turned over and looked at Aengus. He did not move, but his eyes were open. Even in the dimness, they burned the banked-fire blue that I had fallen in love with, the blue of the hot embers of coal. His crow’s wing of black hair fell over one eye. I had fallen in love with that, too. And the straight thick black eyebrows. I even loved the scattering of black freckles across his nose and cheeks. Aengus at the time I met him was as unlike any of the other young men in my small southern town and only slightly larger southern college as a raven to a flock of sparrows. The fact that my mother was appalled by him when I first brought him home from school lit my budding infatuation into a bonfire.

“Angus,” she had murmured sweetly, looking up at him from under her celebrated inch-long lashes. “Like the cows?”

“I wouldn’t be surprised,” Aengus said agreeably, in the rich lilt that could not have been cultivated in the Deep South or possibly anywhere else in the country.

Mother lifted her perfectly arched eyebrows and smiled.

“I don’t believe we know any Anguses, do we, Mother?” she said to my grandmother, who lay reading on the chaise on the screened porch where we had gathered.

“He has fire in his head,” my grandmother murmured, not looking up from her magazine.

We believe she’s starting Alzheimer’s, Mother mouthed confidently to Aengus. Don’t mind anything she says.

Grand gave a disgusted sniff, still not looking up. She was wearing one of the bright silk caftans she had brought home from India, and her vermeil hair was piled on top of her small, elegant head. I thought she looked beautiful.

“Well, she certainly knows her Yeats.” Aengus grinned. “I spell it that way, too, Mrs. Wentworth. With an A before the e. Nobody uses it like that but my mother, but there it is. Will you come dance with me in Ireland?”

“I have no idea what either of you is talking about,” my mother said dismissively. “Thayer, go get us some iced tea. The sweet, in the pitcher. There’s mint in the fridge.”

I got up, but before I left the porch I saw my grandmother lift her head and give Aengus her dazzling full smile. She had been a great beauty; everybody said so. When she smiled like that she still was.

“I will dance with you anywhere, Mr. O’Neill,” she said, and from that moment on she loved him almost as much as I did, until the day she died.

Aengus looked over at me now, half-smiling in the dimness.

“Do you hear that?” I said.

“Yep.”

“What on earth do you think it is?”

“The children of Llyr,” he said, stretching luxuriously. “Grieving for the human children they were before the Dagda turned them into swans.”

“I don’t want to hear any more of your damned Irish bog fairy tales,” I said. “Really, what do you think that is?”

We listened for a moment. The singing children were coming closer. Their song was a real shout now. Its familiarity tickled my tongue.

“Kids having a good time. They’re obviously going somewhere in a car or something, the way they’re moving closer.”

Another moment passed, and then I said, “I know what it is! It’s ‘The Cannibal King’! It’s a great kids’ song; we used to sing it endlessly on the bus to camp and coming home….”

Just then we heard the shushhhh of air brakes and the grinding of big gears changing.

“It is a bus,” I said. “Where on earth are those kids going this early in the morning on a bus? There aren’t that many kids around here….”

“Isn’t there a camp or something that all those assholes in Happy Hollow whomped up for their little darlings?” Aengus said peevishly. “God knows there are enough toddling scions and scionesses over there.”

Our street, Bell’s Ferry Road, ran through the hilly river forest surrounding the Chattahoochee River just to the west of Atlanta. Many of the big old houses had been summer places for well-to-do Atlantans for decades—ours was one of those—and the newer ones were gracefully and conservatively built to blend in. It was a cool ribbon of a street, winding its way down to the bridge that spanned the river.

On the other side of the bridge there was a gated community of houses so jaw-droppingly expensive and baroquely designed that first-time visitors were often stricken to silence—the few who were invited into the enclave. It was called Riverwood, and it gleamed, as my grandfather used to say, like new money on a bear’s behind and was as impenetrable as Gibraltar. It was a mark of distinction among many people we knew not to know anyone who lived there.

To get anywhere near the city or the freeway, the Riverwoodies had to drive back east up Bell’s Ferry Road toward town, and it was all I could do to stop Aengus from throwing rocks or squirrel turds at their Jaguars and Land Rovers and chauffeured limos. I don’t know why Riverwood and its denizens riled him so. Aengus had no temper to speak of, and had never seemed to care who lived where.

But Riverwood maddened him.

“I think it does have a camp,” I said now. “Up in North Georgia near Burnt Mountain, maybe. It’s private; only their kids can go. This would be the time of year for it to start and that was a bus, and that song…”

He grinned...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Burnt Mountain

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Reprint. It's a well-cared-for item that has seen limited use. The item may show minor signs of wear. All the text is legible, with all pages included. It may have slight markings and/or highlighting. Artikel-Nr. 044669830X-8-1

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Artikel-Nr. U13C-04191

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. D09A-02410

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G044669830XI4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G044669830XI4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G044669830XI4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 558418-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 4 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: Kennys Bookstore, Olney, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Good clean copy with some minor shelf wear. Books ship from the US and Ireland. Artikel-Nr. KRA0012694

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. reprint edition. 350 pages. 8.00x5.20x1.00 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. 044669830X

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Burnt Mountain

Anbieter: Kennys Bookshop and Art Galleries Ltd., Galway, GY, Irland

Zustand: Very Good. Good clean copy with some minor shelf wear. Artikel-Nr. KRA0012694

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Irland nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar