Inhaltsangabe

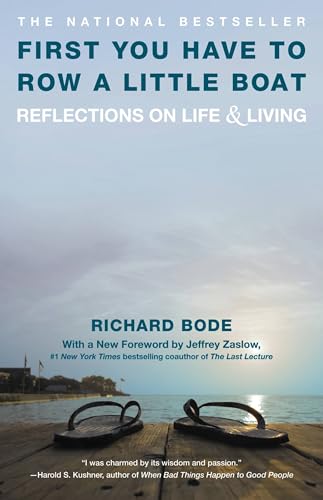

FIRST YOU HAVE TO ROW A LITTLE BOAT first hit shelves in the mid 1990s and has been inspiring readers ever since. Written by a grown man looking back on his childhood, it reflects on what learning to sail taught him about life: making choices, adapting to change, and becoming his own person. The book is filled with the spiritual wisdom and thought-provoking discoveries that marked such books as Walden, The Prophet, and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. For nearly twenty years, it has enchanted and endeared sailors and non-sailors alike, but foremost, anyone who seeks large truths in small things. This refurbished edition will find a place in the hearts of a whole new generation of readers.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Richard Bode worked at McGraw Hill and was editorial director and chief speechwriter at Burston-Marsteller. As a freelance writer, he contributed to Reader's Digest, Good Housekeeping, Sail, Sports Illustrated. He is also the author of Blue Sloop at Dawn (1979), which was excerpted in Sports Illustrated, Newsday Sunday Magazine, and Sail, and wrote the award-winning essay "To Climb the Wind." He died in 2003 of liver cancer.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

First You Have to Row a Little Boat

Reflections on Life & LivingBy Bode, RichardGrand Central Publishing

Copyright © 1995 Bode, RichardAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780446670036

ONE

The Mariner’s Rhyme

When I was a young man I made a solemn vow. I swore I would teach my children to sail. It was a promise never kept.

The exigencies of life—money, work, location, and health—kept me from passing on to my children this legacy which I deem to be the essence of myself. I feel as if I have left something unsaid which I ought to have said, something undone which I ought to have done. I am filled with a lore which I learned as a boy, and I failed to pass it on to my sons and daughters, who will now fail to pass it on to theirs.

I try to forgive myself, but I can’t. No matter how many excuses I make, I am faced with the unalterable fact: I did not teach my children to sail.

In my mind’s eye, in the quiet night, in my vagrant dreams, I see myself doing what I didn’t do. I take my children out one by one in the tender sloop I sold soon after they were born. I teach them to sail out the saltwater creek and to point for the lighthouse across the bay. I teach them to bring the bow or the stern across the face of the wind: to tack or jibe. I teach them to raise or lower the sails, to throw an anchor overboard, to bring the boat up to a mooring in a heavy sea. Through it all I know I am not merely teaching them to sail. I am showing them, hopefully without the taint of preachment, that they are engaged in a metaphor. To sail a boat is to negotiate a life—that is what I want them to understand.

Yet I confess that when I learned to sail as a youth, I had no idea that the lessons of simple seamanship had such universal application and would stand me in such good stead later on. I didn’t sense a wind shift and say to myself, Aha, there’s another one of life’s little lessons. I tacked, jibed, drifted, anchored; I adjusted myself to the conditions I found. I was enjoying myself and acquiring a skill—that’s what I thought.

What I didn’t know was that I was also developing a consciousness, an acute awareness of the relationship between myself and the elements over which I had no control. God gave the wind. It might blow from the east, west, north, or south. It might gust; it might fall off to practically nothing. It might leave me dead becalmed. I didn’t pick the wind; that was imposed by a power far greater than myself. But I had to sail the wind—against it, with it, sideways to it; I had to wait it out with the patience of Job when it didn’t blow—if I wanted to move myself from where I was to where I wanted to go.

As humans we live with the constant presumption of dominion. We believe that we own the world, that it belongs to us, that we have it under our firm control. But the sailor knows all too well the fallacy of this view. The sailor sits by his tiller, waiting and watching. He knows he isn’t sovereign of earth and sky, any more than the fish in the sea or the birds in the air. He responds to the subtle shiftings of the wind, the imperceptible ebbings of the tide. He changes course. He trims his sheets. He sails.

The hurricane, the typhoon, the tsunami, the sudden squall—they are all sharp reminders of the puniness of man when measured against the momentous forces of nature. We aren’t in total charge of our fate. We are subject to death, accident, and disease; we can, without warning, lose love, work, home. An unseen hand can rise at any moment from an unexpected quadrant of the compass and strike us down.

I lost both my parents to death—first my father and then my mother—while I was still a boy. That was a colossal storm, an irreversible wind that changed my destiny. I didn’t command that wind and I couldn’t make it give back what it had taken away. But it was my wind and I had to sail it until it led me at last to a sheltered cove.

All that happened to me a half century ago, and I have survived. In the intervening years I have discovered that—despite the overwhelming nature of that early disaster—day-to-day life isn’t a constant series of crises and calamities. Day-to-day life is like the wind in all its infinite variations and moods. The wind is shifting, constantly shifting, blowing north northeast, then northeast, then north—just as we, ourselves, are constantly shifting, sometimes happy, sometimes angry, sometimes sad. As the sailor sails his winds, so we must sail our moods.

I find myself sharing these thoughts with my children as we sail together through my mythical dreams. But we didn’t sail together and so I never told them—and maybe it’s just as well. If the condition of fatherhood has taught me one thing, it is the difficulty, if not utter impossibility, of passing on to my offspring the lessons of my separate life. I found out, almost after it was too late, that my children weren’t born to learn from my experiences; they were born to learn from their own, and any attempt on my part to substitute my perceptions for theirs was doomed to fail.

The truth is that, for all my sorrow and regret, I can’t go on forever condemning myself for what I did or didn’t do. I learned to sail when I was a youth and my children did not—and that is the sum of it. I don’t know why that happened anymore than I know why some students head straight for the school library and others for the gym. I suspect there are destinations that call to us from a secret place within ourselves and we head for them instinctively.

The silent currents within my own life led me down to the sea in a sailboat when I was still a boy. That was the course I chose for myself—and it has made all the difference in my life and memory.

My children are grown now and involved in their own lives, with their own distinctive triumphs and discoveries, and I am left with a tale untold and no one to tell it to. And so what I write now is in its way an expiation for the sins of omission I committed in the past. I am like the Ancient Mariner, seizing innocent stragglers and wayward passersby and telling them my rhyme.

TWO

The First Thing You Have to Do Is Learn to Row a Little Boat

The urge to sail first came upon me when I was twelve. I stood on the shore and watched the boats dipping, righting themselves, and dipping again in the onshore breeze. It seemed like such a simple sport, far easier than hitting a home run or shooting an oversize ball through a metal hoop. I thought all I had to do was raise the canvas, let it fill with wind, and the boat and I would take off together like a soaring bird. But the first man to get me off the land and into a boat had a decidedly different idea.

His name was Harrison Watts, and in the beginning I knew him only by reputation. He was a legendary sailor who had skippered racing sloops and iceboats as far back as the turn of the century when the Great South Bay froze over every winter from the Long Island mainland clear to the Fire Island Light. If you go down to the end of Ocean Avenue in the old seaside town of Bay Shore, you will find the captain’s wood-frame house still standing there, just north of the boat basin, backing on the busy saltwater creek. For all I know, you may also find his stubby charter boat, the Nimrod—which he...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on...

First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on Life & Living

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. Reprint. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Artikel-Nr. 0446670030-11-1

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on Life & Living

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. M13B-02814

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on Life & Living

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Artikel-Nr. G08D-01664

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat : Reflections on Life and Living

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 3283579-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat : Reflections on Life and Living

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 3283579-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on Life & Living

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0446670030I2N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on Life & Living

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0446670030I2N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on Life & Living

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0446670030I2N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on Life & Living

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0446670030I2N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

First You Have to Row a Little Boat: Reflections on Life & Living

Anbieter: BookOutlet, St. Catharines, ON, Kanada

Paperback. Zustand: New. Paperback. Publisher overstock, may contain remainder mark on edge. Artikel-Nr. 9780446670036B

Neu kaufen

Versand von Kanada nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar