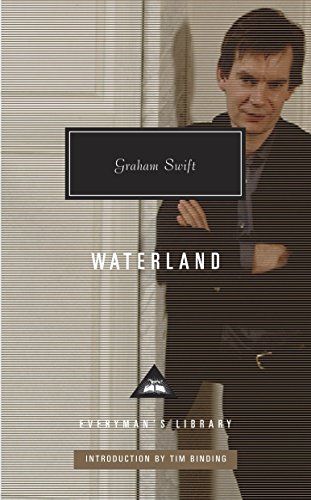

Waterland: Introduction by Tim Binding (Everyman's Library Contemporary Classics Series) - Hardcover

Inhaltsangabe

Graham Swift’s extraordinary masterpiece—a finalist for the Booker Prize—WATERLAND weaves together eels and incest, ale-making and madness, the heartless sweep of history and a family romance as tormented as Greek tragedy into one epic story.

In the flat, watery Fen Country of East Anglia, a passionate history teacher named Tom Crick is being forced into early retirement from the school where he has taught for thirty years. When a student rebelliously questions the value of the subject to which Tom has devoted his life, Tom responds with his own personal retrospective. His story—intertwined with the stories of the local wetlands, the French Revolution, and World War II, among other things—throws light onto the dark circumstances of the current day, revealing how his wife’s tragic youth led to the events surrounding his forced retirement. A monumental tribute to the past, a gripping multigenerational family saga, and a powerful affirmation of the history of self, this exceptional novel illuminates the cycles of time in which we live.

Introduction by Tim Bunding

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Graham Swift is the author of six novels, including the Booker Prize-winning Last Orders. His work has been translated into more than twenty languages. He lives in London, England.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Excerpted from the Introduction

I was sitting on the steps of a caravan. It was winter and the sun was out. The house we had bought was still a wreck. I was a junior editor at Penguin and Graham had given me the first sixty or so pages of his new novel. I had worked on Graham’s second novel Shuttlecock and we had become friends. This was his third novel. It was to be called Waterland.

Almost at once, from the very opening, from those first few promises of stories and ancestry and mother’s milk, I knew instinctively that I was in the presence of something extra- ordinary, something which, when opened fully, was going to envelop me like a glorious burst of light, changing me and the world I lived in forever. Reading a great book is a discovery of its own. The reader feels an almost limitless thrill, like an archaeologist must when stumbling upon a fabled burial site or the lost skull of civilization. It is as if you have discovered this treasure by yourself, and it is yours and yours alone. You take possession of it, guard it jealously. Sure, that moment will pass. Later you will offer up its secrets to others, allow them to talk of it, handle it with (as far as you are concerned) disturbing familiarity, but for those precious hours and days it belongs to no one else, and you hug it closely, protecting every page. That was how I felt, reading those sixty pages. That is how everyone feels, first reading those sixty pages and beyond. It is yours, made just for you. What is more, to some unfathomable degree, it is your story too, in more ways than you thought possible.

Circumstances changed. By the time Graham had finished the novel, I had moved to become editor of Picador. In those days Picador was solely a paperback house, but happily, partly thanks to our previous relationship, it came about that Waterland would be published by Heinemann in hardcover and a year later in paperback, at Picador. I would edit the novel, along with David Godwin at Heinemann. It was a big book for me. It was a big book for Graham. It’s a big book for everyone who reads it.

This is a personal introduction, because it seems to me that is what Waterland is. A personal book, a book that speaks to the innermost core of the reader, digging into the psyche, asking questions, unearthing feelings, seeding ideas, suspicions, that have laid dormant, as to who you are and where you came from, and why it is that doubt, unease, a sense of unspoken, fearful history, is always there, floating under the surface of the waters of the unknown. In that respect there is a quality to it reserved for the most part to the symphony, an underlying motif, an inference, which travels through the novel almost in a different life form, hovering above it all – a note, a call, which lies beyond what is written, emanating from a place that is at one and the same time familiar and utterly new. Reson- ance. You travel through Waterland on its reverberation.

Waterland is a strange book in that, contrary to accepted wisdom, it lies outside Swift’s usual canon. If one removed Waterland from the body of his work and followed the progres- sion of the other novels, they take on a very particular trajec- tory, his aim (or at least one of them) concentrated on quite a specific target, with clear markers laid out along the way, from The Sweet Shop Owner right through to Wish You Were Here. Swift’s overriding intent, as a writer of prose, is to reduce that prose, the word, the sentence, down to its purest form and thereby to unleash the latent power lying within. Swift becomes, if you like, the novelist’s equivalent of a nuclear physicist, working towards the day when, freed from impurities, he breaks the word down into its seemingly lightest, most weightless form, releasing moments of dazzling, almost limitless energy. Two instances of this spring immediately to mind. The airport scene in The Light of Day – a scene of almost religious intensity – and, more recently, the moment in Wish You Were Here when Major Richards, an army officer and the bearer of bad news, steps out of a car and puts on his cap. That is all he does. He reaches out for his peaked cap resting on the passenger seat, gets out of the car and puts it on, yet in that brief action the weight of the world billows out in shock waves. It is difficult, if not impossible to understand quite how or why. Take the sentences apart, examine them and the power simply slips away, but together, under Swift’s tutelage, the intensity is (to use the word in its correct context) awesome. You stand in awe of it. It takes your breath away.

But if all his other novels have been fashioned by the novelist from Los Alamos, then Waterland has been put together in a more familiar manner, made with more familiar tools, from more familiar elements, and in a more familiar design (albeit an astonishing one). Waterland has the appearance of a magnificent engine, a shining and brilliant marvel of construction. It has its oiled wheels, its cogs, its ratchets, its levers. It breathes power. Once begun, there is no stopping Waterland; every part sets another part in motion. It is a glorious, bravura construct, producing story after story in a seemingly unstoppable flow. Reading it, we are conscious of it all (Waterland like a gleaming Flying Scotsman, perfect and polished, powering over the land), and (in the same vein as up on that railway bank, watch- ing the behemoth pass) we stand in wonder of Waterland’s physical appearance, beguiled by its complexities, thrilled by the rhythm and hum of it as the novel does its work. (Waterland does that other steam-engine thing too – being in its presence makes us feel good, makes us feel part of it. It uplifts.) The people – the passengers – are similarly held in thrall to this powerhouse, working through its influence, serving its purpose, carried by its energy and its working parts, its locks and water- ways, its relentless little pump houses. They, like us, are in its power. But though we are (players and readers alike) conscious of it, this great thing, breathing like a beast, its presence never detracts from its intent, never diverts us from its purpose, why it is there, its reason for delivering its stories and its people with a memorizing fecundity, setting them down and moving them (and us) along. We do not mind how deliberately it lies both outside and inside of us, how its power is experienced both internally and externally; in fact we crave it, and are tied to this Waterland as much as those strapped within. We are all affected, readers and passengers alike, harnessed to the wheel, the piston, to the circumstance, to the sluice gates and the waters as they swirl and surround us and carry us off. Here we have it then – Swift as Brunel, brilliant inventor, master builder, blueprint wizard, plotter and planner, a visionary, a user of all materials, creating this Waterland, this wonder of the age, setting his creation free to steam across Great Britain, then continents and oceans to the wider waiting world.

Waterland. There it is. He made it for you and me. What did he do, this hatless Isambard? What did he create exactly? What is it, this novel? What is it?

Let us start, as the narrator might suggest, at the beginning. Open the first page. Take a look at the blueprint. The Contents. They will give you pause for thought.

The first two entries are 1. About the Stars and the Sluice, followed by an oddly resonant phrase (a phrase which accidentally transports us to an age after the book was written), 2. The End of History. So we have three elements already in the mix. Stars - the heavens (space, distance, time), Sluice, a...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Waterland: Introduction by Tim Binding (Everyman's...

Waterland : Introduction by Tim Binding

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 8839246-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Waterland : Introduction by Tim Binding

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 50891448-75

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Waterland

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Zustand: New. Graham Swift is the author of six novels, including the Booker Prize-winning Last Orders. His work has been translated into more than twenty languages. He lives in London, England.Graham Swift&rsquos extraordinary masterpiece&mdasha finalist for th. Artikel-Nr. 897911451

Neu kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar