Inhaltsangabe

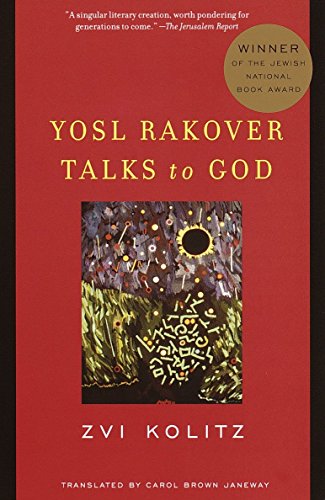

There are two stories here. One is the now legendary tale of a defiant Jew's refusal to abandon God, even in the face of the greatest suffering the world has known, a testament of faith that has taken on an unpredictable and fascinating life of its own and has often been thought to be a direct testament from the Holocaust.

The parallel story is that of Zvi Kolitz, the true author, whose connection to Yosl Rakover has been obscured over the fifty years since its original appearance. German journalist Paul Badde tells how a young man came to write this classic response to evil, and then was nearly written out of its history. With brief commentaries by French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and Leon Wieseltier, author of Kaddish, this edition presents a religious classic and the very human story behind it.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Zvi Kolitz lives in New York City.

Translated from the German by Carol Brown Janeway.

Von der hinteren Coverseite

There are two stories here. One is the now legendary tale of a defiant Jew's refusal to abandon God, even in the face of the greatest suffering the world has known, a testament of faith that has taken on an unpredictable and fascinating life of its own and has often been thought to be a direct testament from the Holocaust.

The parallel story is that of Zvi Kolitz, the true author, whose connection to Yosl Rakover has been obscured over the fifty years since its original appearance. German journalist Paul Badde tells how a young man came to write this classic response to evil, and then was nearly written out of its history. With brief commentaries by French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and Leon Wieseltier, author of Kaddish, this edition presents a religious classic and the very human story behind it.

Aus dem Klappentext

o stories here. One is the now legendary tale of a defiant Jew's refusal to abandon God, even in the face of the greatest suffering the world has known, a testament of faith that has taken on an unpredictable and fascinating life of its own and has often been thought to be a direct testament from the Holocaust.

The parallel story is that of Zvi Kolitz, the true author, whose connection to Yosl Rakover has been obscured over the fifty years since its original appearance. German journalist Paul Badde tells how a young man came to write this classic response to evil, and then was nearly written out of its history. With brief commentaries by French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and Leon Wieseltier, author of Kaddish, this edition presents a religious classic and the very human story behind it.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

In one of the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, preserved in a little bottle and concealed amongst heaps of charred stone and human bones, the following testament was found, written in the last hours of the ghetto by a Jew named Yosl Rakover.

Warsaw, 28 April 1943

I, Yosl, son of David Rakover of Tarnopol, a follower of the Rabbi of Ger and descendant of the righteous, learned, and holy ones of the families Rakover and Maysels, am writing these lines as the houses of the Warsaw Ghetto are in flames, and the house I am in is one of the last that has not yet caught fire. For several hours now we have been under raging artillery fire and all around me walls are exploding and shattering in the hail of shells. It will not be long before this house I'm in, like almost all the houses in the ghetto, will become the grave of its inhabitants and defenders.

Fiery red bolts of sunlight piercing through the little half-walled-up window in my room, out of which we've been shooting at the enemy day and night, tell me that it must be almost evening, just before sundown. The sun probably has no idea how little I regret that I shall never see it again.

A strange thing has happened to us: all our ideas and feelings have changed. Death, quick death that comes in an instant, is to us a deliverer, a liberator who breaks our chains. The animals of the forest seem so dear and precious to me that it pains my heart to hear the criminals who are now masters of Europe likened to them. It is not true that there is something of the animal in Hitler. He is -- I am utterly convinced of it -- a typical child of modern man. Mankind has borne him and raised him and he is the direct, unfeigned expression of mankind's innermost, deepest-hidden urges.

In a forest where I was hiding, I met a dog one night, a sick, starving, crazed dog, his tail between his legs. Immediately we felt our common situation, for no dog's situation is a whit better than our own. He rubbed up against me, buried his head in my lap, and licked my hands. I don't know if I have ever wept the way I wept that night; I wrapped myself around his neck and cried like a child. If I stress the fact that I envied the animals then, no one should be surprised. But what I felt back then was more than envy; it was shame. I was ashamed be-fore the dog, for being not a dog but a man. That is how it is, and such is the spiritual condition we have reached: life is a calamity -- death, a liberator -- man, a plague -- beast, an ideal -- day, an abomination -- night, a comfort.

Millions of people in the great, wide world, in love with the day, the sun, and the light, neither know nor have the slightest intimation of the darkness and calamity the sun brings us. The criminals have made of it an instrument in their hands; they have used the sun as a searchlight to reveal the footprints of the fugitives trying to escape them. When I hid myself in the forests with my wife and my children -- there were six of them then -- it was the night, only the night, that concealed us in her heart. The day delivered us to our pursuers, who were hunting our souls. How can I ever forget the day of that German firestorm that raged over thousands of refugees on the road from Grodno to Warsaw? Their planes rose in the early dawn with the sun, and all day long they slaughtered us unceasingly. In this massacre that came down from the skies my wife died with our youngest child, seven months old, in her arms, and two of my surviving five children vanished that same day without a trace. David and Jehuda were their names, the one was four years old, the other six.

When the sun went down the handful of survivors moved on again toward Warsaw. But I combed through the woods and fields with my three remaining children, searching for the other two on the slaughterground. "David! -- Jehuda!" -- all night long our cries slashed like knives through the deadly silence that surrounded us, and all that answered us from the woods was an echo, helpless, heartrending, suffering as we suffered, a distant voice of lamentation. I never saw the two boys again, and I was told in a dream not to worry over them any more: they were in the hands of the Lord of Heaven and Earth. My other three children died in the Warsaw Ghetto within a year.

Rachel, my little daughter, ten years old, had heard that there were scraps of bread to be found in the city garbage cans on the other side of the walls of the ghetto. The ghetto was starving, and the starving lay like rags in the streets. People were prepared to die any death, but not death by starvation. This is probably because in a time when systematic persecution gradually destroys every other human need, the will to eat is the last one that endures, even in the presence of a longing for death. I was told of a Jew, half-starved, who said to someone, "Ah, how happy I would be to die if one last time I could sit down to a meal like a mentsh!"

Rachel had said nothing to me about her plan to steal out of the ghetto -- a crime that carried the death penalty. She went off on her dangerous journey with a friend, another girl of the same age.

In the dark of night she left home and at dawn she was discovered with her little friend outside the gates of the ghetto. The Nazi sentries and dozens of their Polish helpers immediately went in pursuit of the Jewish children who had dared to hunt in the garbage for a lump of bread so as not to die of hunger. People who had experienced this human hunt at first hand could not believe what they were seeing. Even for the ghetto this was new. You might have thought that dangerous escaped criminals were being chased as this terrifying pack ran amok after the two half-starved ten-year-old children. They couldn't keep up this race for long before one of them, my daughter, having expended the last of her strength, collapsed on the ground in exhaustion. The Nazis drove holes through her skull. The other girl escaped their clutches, but she died two weeks later. She had lost her mind.

Jacob, our fifth child, a boy of thirteen, died of tuberculosis on the day of his bar mitzvah. His death was a release for him. The last child, my daughter Eva, lost her life at the age of fifteen in a "roundup of children" that began at sunrise on the final Rosh Hashanah and lasted till sundown.

On that first day of the New Year, hundreds of Jewish families lost their children before evening came.

Now my hour has come, and like Job I can say of myself -- naked shall I return unto the earth, naked as the day I was born. My years are forty-three, and when I look back on the years that have gone by, I can say with certainty -- insofar as any man may be certain of himself -- that I have lived an honorable life. My heart has been filled with the love of God. I have been blessed with success, but the success never went to my head. My portion was ample. But though it was mine, I treated it not as mine: following the counsel of my rabbi, I considered my possessions to have no possessor. Should they lure someone to take some part of them, this should not be counted as theft, but as though that person had taken unclaimed goods. My house stood open for all who were needy, and I was happy when I was given the opportunity to perform a good deed for others. I served God with devotion, and my only petition of Him was that He allow me to serve Him "with all my heart and with all my soul and with all my strength."

I cannot say, after all I have lived through, that my relation to God is unchanged. But with absolute certainty I can say that my faith in Him has not altered by a hairsbreadth. In earlier times, when my life was good, my relation to Him was as if to one who gave me gifts without end, and to whom I was therefore always somewhat in debt. Now my relation to Him is as to one who is also in my debt -- greatly in...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Yosl Rakover Talks to God (Vintage International)

Yosl Rakover Talks to God

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 5403965-75

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Yosl Rakover Talks to God

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 3224348-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Yosl Rakover Talks to God

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375708405I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Yosl Rakover Talks to God

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375708405I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Yosl Rakover Talks to God

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375708405I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Yosl Rakover Talks to God

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375708405I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Yosl Rakover Talks to God

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375708405I3N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Yosl Rakover Talks to God (Vintage International)

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. GOR006093468

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Yosl Rakover Talks to God

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. 112 pages. 8.00x5.50x0.50 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. x-0375708405

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar