Inhaltsangabe

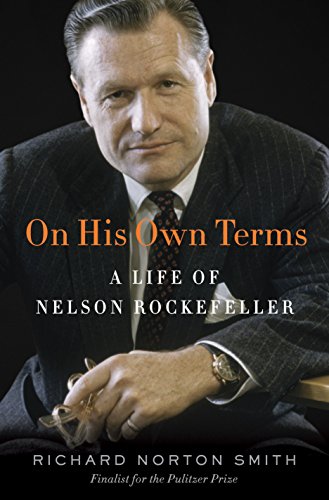

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY THE BOSTON GLOBE, BOOKLIST, AND KIRKUS REVIEWS • From acclaimed historian Richard Norton Smith comes the definitive life of an American icon: Nelson Rockefeller—one of the most complex and compelling figures of the twentieth century.

Fourteen years in the making, this magisterial biography of the original Rockefeller Republican draws on thousands of newly available documents and over two hundred interviews, including Rockefeller’s own unpublished reminiscences.

Grandson of oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, Nelson coveted the White House from childhood. “When you think of what I had,” he once remarked, “what else was there to aspire to?” Before he was thirty he had helped his father develop Rockefeller Center and his mother establish the Museum of Modern Art. At thirty-two he was Franklin Roosevelt’s wartime coordinator for Latin America. As New York’s four-term governor he set national standards in education, the environment, and urban policy. The charismatic face of liberal Republicanism, Rockefeller championed civil rights and health insurance for all. Three times he sought the presidency—arguably in the wrong party. At the Republican National Convention in San Francisco in 1964, locked in an epic battle with Barry Goldwater, Rockefeller denounced extremist elements in the GOP, a moment that changed the party forever. But he could not wrest the nomination from the Arizona conservative, or from Richard Nixon four years later. In the end, he had to settle for two dispiriting years as vice president under Gerald Ford.

In On His Own Terms, Richard Norton Smith re-creates Rockefeller’s improbable rise to the governor’s mansion, his politically disastrous divorce and remarriage, and his often surprising relationships with presidents and political leaders from FDR to Henry Kissinger. A frustrated architect turned master builder, an avid collector of art and an unabashed ladies’ man, “Rocky” promoted fallout shelters and affordable housing with equal enthusiasm. From the deadly 1971 prison uprising at Attica and unceasing battles with New York City mayor John Lindsay to his son’s unsolved disappearance (and the grisly theories it spawned), the punitive drug laws that bear his name, and the much-gossiped-about circumstances of his death, Nelson Rockefeller’s was a life of astonishing color, range, and relevance. On His Own Terms, a masterpiece of the biographer’s art, vividly captures the soaring optimism, polarizing politics, and inner turmoil of this American Original.

Praise for On His Own Terms

“[An] enthralling biography . . . Richard Norton Smith has written what will probably stand as a definitive Life. . . . On His Own Terms succeeds as an absorbing, deeply informative portrait of an important, complicated, semi-heroic figure who, in his approach to the limits of government and to government’s relation to the governed, belonged in every sense to another century.”—The New Yorker

“[A] splendid biography . . . a clear-eyed, exhaustively researched account of a significant and fascinating American life.”—The Wall Street Journal

“A compelling read . . . What makes the book fascinating for a contemporary professional is not so much any one thing that Rockefeller achieved, but the portrait of the world he inhabited not so very long ago.”—The New York Times

“[On His Own Terms] has perception and scholarly authority and is immensely readable.”—The Economist

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Richard Norton Smith is the author of Thomas E. Dewey and His Times (a finalist for the 1983 Pulitzer Prize); An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover; The Harvard Century: The Making of a University to a Nation; The Colonel: The Life and Legend of Robert R. McCormick, 1880-1955; and Patriarch: George Washington and the New American Nation. He has served as the director of presidential libraries commemorating Abraham Lincoln, Herbert Hoover, Dwight Eisenhower, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan. As C-SPAN’s in-house historian, he appears frequently on that network. He has also been a regular contributor to the PBS NewsHour, and an ABC News presidential historian.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

9780375505805|excerpt

Smith / ON HIS OWN TERMS

One

The House That Sugar Built

I had a grandfather—don’t jump to any conclusions; this was my mother’s father. He was the collector of art. He also happened to be a politician, which is a rather unusual combination, to be frank.

—Nelson A. Rockefeller

1

The headlines were predictable. croesus captured. beauty to wed wealth. son of richest man in the world gives up church and goes in for dancing to win miss aldrich. Americans in the autumn of 1901 were both fascinated and repelled by the pending alliance between the world’s greatest fortune and the country’s dominant lawmaker. The site of the wedding was never in doubt. Although the bride expressed her preference for a modest ceremony in a small Warwick church, and the groom would have been perfectly happy to plight his troth before a handful of witnesses in New York’s Little Church Around the Corner, the choice didn’t rest with Abby Greene Aldrich or John D. Rockefeller, Jr. In the Aldrich household, senatorial privilege governed; unmitigated by senatorial courtesy, it reserved all questions of importance to the imperious figure popularly labeled “the General Manager of the United States.”

Virtually forgotten today, for twenty years straddling the end of the nineteenth century, Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich pulled the nation’s financial strings in tandem with Wall Street confederates like J. P. Morgan and Paul Warburg. “He was so much the man of power that he never thought about his power,” wrote Aldrich’s official biographer. “It was natural to him, like breathing air.” Much the same would be said of the senator’s grandson and namesake, who emulated his appetite for command, his chronic restlessness, and his unabashed delight in art at once spiritual and sensual. “Most people don’t know what they want!” Aldrich grumbled. This was not a criticism frequently directed at the senior senator from Rhode Island. The recent assassination of President William McKinley, long a champion of economic protectionism, may have been grim news indeed for like-minded Republicans like Aldrich. Yet the death of a president, however untimely, could not be allowed to interfere with the wedding of Abby Aldrich four weeks later.

If anything, uncertainty about McKinley’s swashbuckling successor, Theodore Roosevelt, lent a note of urgency to the invitations Aldrich dispatched to his Capitol Hill colleagues. “Come right to Warwick and stay,” he told one. “We will have a committee [meeting] right away after. There are a number of things I want to talk to you about.” The new president, precluded by the requirements of public mourning from attending the nuptials, was nonetheless careful to solicit senatorial counsel as he composed his first, defining message to Congress. Aldrich took such deference as his due. As a child he had come to see himself among the elect, a status reinforced by his mother’s claims of descent from New England patriarchs John Winthrop and Roger Williams. While still a newcomer to the Providence City Council, Aldrich had resolved to build a great country seat on the west shore of Narragansett Bay at Warwick. Even now, architects were drawing plans for a seventy-room château, serviced by a two-hundred-yard private railroad laid down to muffle the clatter of tradesmen making deliveries. The parklike setting already boasted a large stone teahouse, in the elegant ballroom of which Abby and John would exchange their vows.

None of the several hundred invited guests who made their way there on the morning of October 9, 1901, by steamer or special streetcar could fail to be impressed by the waterfront estate Aldrich called Indian Oaks and muckraking journalists made notorious as the House That Sugar Built. Its owner, the son of a millworker from Foster, Rhode Island, had traveled an improbable road in his sixty years. Before his tenth birthday, Aldrich passed up a visiting circus and, with the money saved, purchased the self-improving volume A Tinker’s Son, or, I’ll Be Somebody Yet. At seventeen, he landed a job as a wholesale grocer’s clerk in the state capital of Providence. Attending evening lectures at a local lyceum to compensate for a meager formal education, Aldrich paid special attention to the rules of debate and parliamentary procedure. The attack on Fort Sumter interrupted his bookkeeping labors, but only briefly; a bout of typhoid fever earned him a discharge from the Tenth Rhode Island Volunteers garrisoning wartime Washington.

Sickened by the possibility that he might remain one of the “dumb driven cattle” constituting the bulk of humanity, Aldrich returned to Providence in the autumn of 1862. He began courting Abby Pearce Chapman, a Mayflower descendant to whom he confided a fierce resolution to achieve, “willingly or forcibly wrested from a selfish world Success! Counted as the mass count it, by dollars and cents!” The ambitious clerk dreaded anonymity only slightly less than the soul-killing drudgery of the ledger book. Within a year of their 1866 marriage, Nelson and Abby welcomed a son, christened Nelson Jr. The boy’s death at the age of four devastated his parents. But it was the father who fled to the Old World, leaving Abby to console herself as he applied the healing balm of art.

At the Parthenon (“the most sublime of all temples or churches”), Aldrich was nearly overcome by the urge to prostrate himself on the marble pavement. Rejecting the stern theology of his New England fathers, Aldrich found inspiration in the parallel universe of artistic and literary expression. Denied creative talent, Aldrich was frustrated a second time when his hopes of becoming a great orator, a modern-day Cicero, went glimmering. Politics beckoned. Elected to the Providence City Council in 1869, Aldrich served simultaneously as president of the city’s Board of Trade and the First National City Bank. After making his peace with the Republican boss of Rhode Island, General Charles Brayton, he won a seat in the state legislature. His subsequent ascent to the Speaker’s chair foreshadowed two terms in the national House of Representatives and three decades as a senatorial powerhouse.

His reliance on government as an engine of democratic capitalism placed Aldrich in the nationalistic camp of Alexander Hamilton, a financial wizard rejected by the very people whose democratic experiment he capitalized. Hamilton believed that only by linking the interests of the state “in an intimate connection” with citizens of great wealth could the success of the young republic be assured. For Nelson Aldrich, the line demarking self-interest from the public good was indistinct, if not invisible. From an early age, Aldrich the self-made aristocrat entertained visions of grandeur centered on Warwick Neck. Lacking the cash to realize them, the freshman senator and his growing family made do with a suite of rooms in a Washington hotel, supplemented by rented houses in Providence. Eventually there would be eleven Aldrich children, eight of whom survived infancy. These included a daughter born in October 1874 and named for her mother. As the elder Abby faded under the strain of repeated pregnancies and the physical and emotional distance imposed by Nelson’s political pursuits, the second Abby came to fill the void in her father’s life. Belying his reactionary image, Nelson Aldrich was a thoroughgoing progressive when it came to educating women. Thus his daughter began her formal schooling with a Quaker governess, precursor to Miss Abbott’s School for Young Ladies in Providence, at which modern...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Suchergebnisse für On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375505806I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375505806I3N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375505806I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375505806I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375505806I3N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375505806I3N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0375505806I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

On His Own Terms : A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 4068431-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

On His Own Terms : A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 4501491-20

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. Good dust jacket. With remainder mark. Artikel-Nr. E14A-04339

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar