Inhaltsangabe

A brilliant and urgent appraisal of one of the most profound conflicts of our time

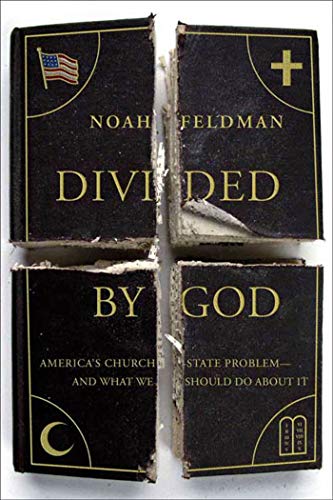

Even before George W. Bush gained reelection by wooing religiously devout "values voters," it was clear that church-state matters in the United States had reached a crisis. With Divided by God, Noah Feldman shows that the crisis is as old as this country--and looks to our nation's past to show how it might be resolved.

Today more than ever, ours is a religiously diverse society: Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist as well as Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish. And yet more than ever, committed Christians are making themselves felt in politics and culture.

What are the implications of this paradox? To answer this question, Feldman makes clear that again and again in our nation's history diversity has forced us to redraw the lines in the church-state divide. In vivid, dramatic chapters, he describes how we as a people have resolved conflicts over the Bible, the Pledge of Allegiance, and the teaching of evolution through appeals to shared values of liberty, equality, and freedom of conscience. And he proposes a brilliant solution to our current crisis, one that honors our religious diversity while respecting the long-held conviction that religion and state should not mix.

Divided by God speaks to the headlines, even as it tells the story of a long-running conflict that has made the American people who we are.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Noah Feldman is the Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard University, where he is also founding director of the Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law. A leading public intellectual, he is a contributing writer for Bloomberg View and the author of numerous books, including The Broken Constitution, Divided by God, and The Fall and Rise of the Islamic State.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Divided by God

America's Church-State Problem--And What We Should Do about ItBy Noah FeldmanFarrar Straus Giroux

Copyright © 2006 Noah FeldmanAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780374530389

Chapter One

THE ORIGINS

On June 12, 1788, James Madison, the father of religious liberty in America, stood before the Virginia convention debating the ratification of the Constitution and opposed the First Amendment. There was no need for the Constitution to prohibit an established religion or to protect religious liberty, Madison argued. Religious diversity would guarantee religious freedom by itself: "For where there is such a variety of sects, there cannot be a majority of any one sect to oppress and persecute the rest." There were so many different religious denominations in the United States that no one group would ever be able to impose its will over the others. It was pointless to prohibit what no one group could ever hope to accomplish.

The assembled Virginians knew Madison as the man who had led the fight to disestablish the Anglican church in Virginia, guarantee religious liberty, and block the state even from collecting an assessment that could be earmarked for distribution to the religious teacher of one's choice. No American, not even Jefferson, had better credentials on the separation of church and state. Virginia's religious dissenters, Presbyterians and Baptists who had been Madison's close allies in the five-year struggle in the state legislature, wanted a guarantee in the federal Constitution that would parallel what they had won at the state level. Notwithstanding Madison's predictive judgment about the likely effects of diversity, they still feared the possibility that someday one denomination really might be able to establish a national religion that would make them pay taxes in support of a church to which they did not belong. The solution they demanded was an amendment to the Constitution to guarantee religious liberty. Why was Madison suddenly on the wrong side?

PRINCIPLE AND POLITICS

In the solution to this puzzle lies the key to the most basic question about the relationship between church and state in the United States: Why do we have a First Amendment prohibiting the establishment of religion and protecting the free exercise thereof? The answer combines principle and politics. The principled reason behind the religion clauses of the First Amendment was to protect the liberty of conscience of religious dissenters-and everybody involved in the process understood that fact. The political reason for the clauses was that no one in the new United States opposed the idea of religious liberty, and given the religious diversity among Americans, no one denomination seriously believed it could establish a national religion of its own. Although 95 percent were Protestants of some sort (as of 1780 there were just fifty-six Catholic churches and five Jewish congregations in the whole country), American Protestants ranged from Anglican (soon to be renamed Episcopalian) and Congregationalist to Presbyterian, Baptist, Quaker, and beyond. Practically speaking, the fact of religious diversity made a nationally established religion impossible. The sovereign people belonged not to one faith, but several. The solution, adopted by the first Congress, which wrote the Bill of Rights, passed it, and sent it to the states for ratification, was to prohibit a national establishment and guarantee free exercise.

Madison was profoundly committed to religious liberty and opposed to religious establishment of any kind; in fact, he believed that no government had the right to take any action in the religious sphere-certainly not the proposed new federal government, whose powers were limited to those granted in the draft Constitution he had done so much to produce. In addition to principle, Madison had another reason for judging an amendment unnecessary. In thinking about the creation of a new federal republic that would perfect the union of thirteen still-disparate states, he had developed the world-changing idea that America's diverse factions could counterbalance each other, instead of tearing the country apart. Applying this notion to religion convinced Madison that only national politics, not a parchment promise, could guarantee religious liberty and nonestablishment.

But Madison was also a politician, and his constituency of religious dissenters was having none of his argument. So Madison did what any politician would do, only better: he abandoned the stance he took at the Virginia ratifying convention, got himself elected to the first House of Representatives, and took the lead in drafting the religion clauses of the First Amendment. Because he combined principle and politics when it came to the religion clauses, Madison's story is central if we want to understand the early history of the church-state relationship in the United States.

That history is under dispute today as never before. In the media, in scholarly writing, and in judicial opinions, one can hear both that the framers gave us a "Godless Constitution" with strong separation between church and state, and, to the contrary, that the Constitution assumed a Christian nation and prohibited the federal government only from officially preferring one denomination to others. The story we tell about our founding is our creation myth, so it is not surprising that the framers' decisions and beliefs regarding religion and government loom very large in the current debate about the subject. Both legal secularists and values evangelicals have a huge stake in claiming the framers' original authority for their views.

But the truth is that both of these perspectives are wrong, both developed over the last fifty years in order to justify positions in a contemporary legal and cultural fight under circumstances very different from the framers'. In what follows, I briefly sketch the most prominent views on the subject-then go back to the beginning and set the record straight.

THE BATTLE LINES

The framers undertook an extraordinary experiment when they broke from past practice and prohibited the establishment of religion by the federal government while guaranteeing free exercise -on that much, everyone can agree. In England and on the European continent, in Catholic and Protestant countries alike, it had long been assumed that a close relationship between established religion and government was necessary to maintain social order and national cohesion. The framers were experimenting across the board, trying to create a federal union out of self-governing states despite the certainty of mainstream theorists like the influential Montesquieu that a geographically large republic could not survive. That innovation came out of necessity. The Articles of Confederation, loosely tying the original thirteen states to one another, had failed politically and economically, and the framers had little choice but to try something new. But why experiment in the realm of church and state?

One traditional answer begins with Thomas Jefferson, the most controversial founding father in his lifetime and beyond, and the author of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which ended state financial support for organized religion in Virginia. Determined to be remembered for the statute, Jefferson ordered it mentioned on his tombstone as one of his three greatest accomplishments, alongside the authorship of the Declaration of Independence and the foundation of the University of...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem--And...

Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem--and What We Should Do About It

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: As New. Like New condition. A near perfect copy that may have very minor cosmetic defects. Artikel-Nr. Z07H-01257

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem--and What We Should Do About It

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. K14B-01805

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem--and What We Should Do About It

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Artikel-Nr. S22L-00558

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem--And What We Should Do about It

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0374530386I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem--And What We Should Do about It

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0374530386I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Divided by God : America's Church-State Problem--And What We Should Do about It

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 5584953-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 3 verfügbar

Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem--and What We Should Do About It

Anbieter: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Artikel-Nr. mon0003411177

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem--and What We Should Do About It

Anbieter: Magers and Quinn Booksellers, Minneapolis, MN, USA

paperback. Zustand: Acceptable. May have underlining, highlighting, margin notes, remainder marks, inscriptions, book plates, tears, significant wear, and/or a missing dust jacket, box, or discs. Damaged item. Artikel-Nr. 1362523

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Divided by God

Anbieter: PBShop.store US, Wood Dale, IL, USA

PAP. Zustand: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Artikel-Nr. L2-9780374530389

Neu kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar

Divided by God

Anbieter: Ammareal, Morangis, Frankreich

Softcover. Zustand: Très bon. Légères traces d'usure sur la couverture. Ammareal reverse jusqu'à 15% du prix net de cet article à des organisations caritatives. ENGLISH DESCRIPTION Book Condition: Used, Very good. Slight signs of wear on the cover. Ammareal gives back up to 15% of this item's net price to charity organizations. Artikel-Nr. E-815-661

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Frankreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar