Inhaltsangabe

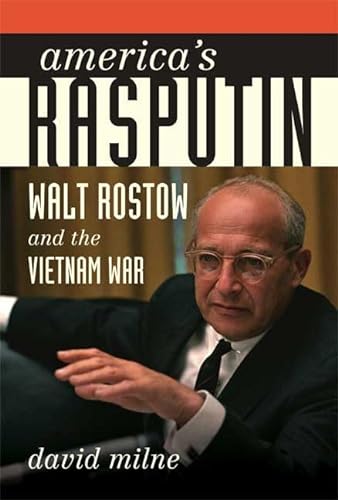

Examines the life, political career, and significant influence of Walt Rostow, a professor of economic history at MIT and foreign-policy advisor to presidents Kennedy and Johnson, critically analyzing his impact on presidential decision-making, especially in terms of the escalation of American military involvement in Vietnam.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

On february 27, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson’s closest foreign-policy advisers gathered in the White House to discuss a war that had spiraled out of control. A month previously South Vietnam’s major towns and cities had been overrun by communist insurgents dedicated to unifying their nation under North Vietnam’s president, Ho Chi Minh. Johnson had been promised “light at the end of the tunnel” at the end of 1967, and the Tet Offensive (so called because the assault coincided with the eve of Tet, the lunar New Year) devastated his administration’s credibility. Most recognized that while the campaign was a conventional military defeat for the insurgents, their psychological victory had been comprehensive. Who could now believe that the United States was winning the war? The mood in the West Wing was accordingly funereal.

The outgoing secretary of defense, Robert S. McNamara, spoke first. He reported that General William Westmoreland, America’s ranking field commander, wanted the president to dispatch 206,000 additional U.S. combat troops to Vietnam—bringing total troop levels close to 700,000. To satisfy Westmoreland’s request, McNamara calculated that the president would have to call up 150,000 reserves, extend the draft, and sanction a $15 billion increase in the defense budget. To pay for this, Johnson would be forced to increase taxes and make swinging cuts to his progressive domestic program—commit electoral suicide, in other words. Aside from the fiscal and political sacrifice required, McNamara wondered how Westmoreland was so certain that 206,000 more troops would do the job where half a million had failed.

McNamara’s successor as defense secretary spoke next. Playing devil’s advocate, Clark Clifford asked the group to consider whether Westmoreland’s request was sufficient. Why not call up a further 500,000 or even a million troops? Why not err on the side of caution to get the job done without fear of further failure? “That and the status quo have the virtue of clarity,” McNamara agreed matter-of-factly. “I do not understand the strategy in putting in 206,000 men. It is neither enough to do the job, nor an indication that our role must change.” McNamara believed that the time was now right to declare that the South Vietnamese government was secure and viable—accomplishing the original American objective—and then swiftly locate an exit strategy.

The president’s national security adviser, Walt Whitman Rostow, regarded McNamara’s assessment as ill-considered and defeatist. The Tet Offensive represented a defeat for the communist insurgents and this was no time to take any backward steps. Rostow explained that captured documents proved that the enemy was “disappointed” and unable to mount heavy attacks on the cities. He wanted to reinforce Westmoreland with the soldiers he required and further recommended that the military should up the ante by intensifying the American bombing campaign. The South Vietnamese National Liberation Front (NLF) was in disarray—some forty thousand insurgents had been killed during the assault—and Rostow believed that the Tet Offensive, if exploited correctly, might represent the birth pangs of a sustainable, noncommunist South Vietnam.

The national security adviser’s pugnacity was predictable, but something snapped in McNamara when Rostow finished speaking. The two men had clashed unpleasantly over the past two years, but their relationship was about to hit a new low. While Rostow was unfailingly optimistic about military prospects in Vietnam, McNamara had become disillusioned with the conflict in early 1966, and had henceforth urged LBJ to consider de-escalation. Rostow invariably prevailed in these debates, but it was McNamara’s last day in office and he was not going to miss an opportunity to confront his bureaucratic nemesis. “What then?” the defense secretary demanded of Rostow’s plan. “This goddamned bombing campaign, it’s been worth nothing, it’s done nothing, they’ve dropped more bombs than in all of Europe in all of World War II and it hasn’t done a fucking thing.” Speaking with the intensity of a tortured soul who had helped create an unnecessary war, the defense secretary finished his sentence, broke down, and wept. Rostow could only look on, stunned, as Robert McNamara—once described as an “IBM machine with legs”—melted down in a room filled with Washington’s most powerful men.1

In january 1961 the atmosphere in the nation’s capital could not have been more different. The United States was set to inaugurate a president whose popular appeal exceeded that of any twentieth-century incumbent not born to the name Roosevelt. John F. Kennedy was a cerebral, photogenic Massachusetts liberal with a young family and a glamorous wife. He possessed an energy that contrasted sharply with the staid conservatism of his Republican predecessor. In foreign policy Kennedy’s instincts compelled him to favor action over inaction and internationalism over parochialism. Courage under pressure was a trait that he had cultivated assiduously throughout his career. If Kennedy was clearly for anything, it was for taking the fight to America’s enemies.

The United States faced a clear enemy in 1960 and, unlike today, schoolchildren could find it on a map. The Soviet Union existed not just as America’s tactical and strategic competitor, but it also propagated a universal value system that was dedicated to replacing the liberal capitalist worldview championed by the United States. The McCarthyite era had convinced many Americans of the relentless, insidious nature of their enemy. And while the hysteria had passed—Joseph McCarthy had died in lonely ignominy in 1957—the nation still bore the scars that are inflicted when paranoiac bullying goes unchallenged by a fearful Congress. The pragmatic Nikita Khrushchev had succeeded the tyrant Josef Stalin, but the Soviet Union still instilled fear. Yet Kennedy was aware that communism’s danger lay not only in its potential to damage the United States and Western Europe. The so-called Third World was the arena in which the United States and the Soviet Union would battle for ascendancy. Who would find communism’s utopian promise of absolute equality most appealing? The answer: those people living in nations newly liberated from European colonialism and driven to despair by the inequities of daily life.

A day prior to his glittering inauguration, Kennedy announced that Walt Rostow would serve as his deputy assistant for national security affairs. Rostow’s appointment was greeted enthusiastically by the media, academia, and the Democratic Party. As a distinguished professor of economic history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Rostow had established a reputation as an articulate champion of Third World development. Through the 1950s Rostow had worked tirelessly to convince President Dwight D. Eisenhower that increasing America’s foreign-aid provision was morally unavoidable in a time of economic abundance and tactically essential in an age of global cold war. While Eisenhower was unmoved by Rostow’s campaign for an international New Deal, Kennedy found the young professor’s rationale compelling. If the Cold War was essentially a high-stakes geopolitical chess game—as defense intellectuals opined—then the pawns were surely critical to any winning strategy. If the United States continued to ignore the world’s failing nations, what was to stop them from seeking an ideological alliance with the Soviet Union?...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam...

America's Rasputin : Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. 1 Edition. Former library copy. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 7484289-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin : Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1 Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 467481-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin : Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1 Edition. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 467482-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. First Edition. With dust jacket. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Artikel-Nr. 0374103860-11-1-29

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0374103860I3N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0374103860I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0374103860I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: WeBuyBooks, Rossendale, LANCS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. A copy that has been read but remains in clean condition. All of the pages are intact and the cover is intact and the spine may show signs of wear. The book may have minor markings which are not specifically mentioned. Ex library copy with usual stamps & stickers. Artikel-Nr. wbs6439638390

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: HALCYON BOOKS, LONDON, Vereinigtes Königreich

hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. ALL ITEMS ARE DISPATCHED FROM THE UK WITHIN 48 HOURS ( BOOKS ORDERED OVER THE WEEKEND DISPATCHED ON MONDAY) ALL OVERSEAS ORDERS SENT BY TRACKABLE AIR MAIL. IF YOU ARE LOCATED OUTSIDE THE UK PLEASE ASK US FOR A POSTAGE QUOTE FOR MULTI VOLUME SETS BEFORE ORDERING. Artikel-Nr. mon0000937939

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War

Anbieter: JuddSt.Pancras, London, Vereinigtes Königreich

Hardcover. Zustand: As New. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: As New. 1st Edition. Artikel-Nr. c286104

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar