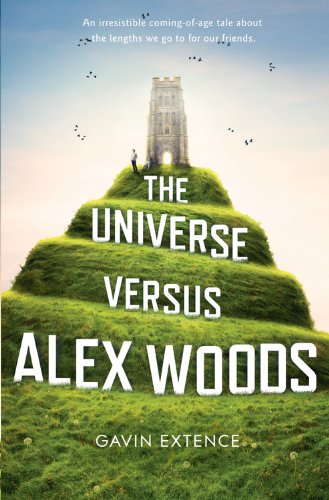

Verwandte Artikel zu The Universe Versus Alex Woods

Inhaltsangabe

A rare meteorite struck Alex Woods when he was ten years old, leaving scars and marking him for an extraordinary future. The son of a fortune teller, bookish, and an easy target for bullies, Alex hasn't had the easiest childhood.

But when he meets curmudgeonly widower Mr. Peterson, he finds an unlikely friend. Someone who teaches him that that you only get one shot at life. That you have to make it count.

So when, aged seventeen, Alex is stopped at customs with 113 grams of marijuana, an urn full of ashes on the front seat, and an entire nation in uproar, he's fairly sure he's done the right thing . . .

Introducing a bright young voice destined to charm the world, The Universe Versus Alex Woods is a celebration of curious incidents, astronomy and astrology, the works of Kurt Vonnegut and the unexpected connections that form our world.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Gavin Extence was born in 1982 and grew up in the interestingly named village of Swineshead, England. From the ages of 5-11, he enjoyed a brief but illustrious career as a chess player, winning numerous national championships and travelling to Moscow and St. Petersburg to pit his wits against the finest young minds in Russia. He won only one game.

Gavin now lives in Sheffield with his wife, baby daughter and cat. He is currently working on his next novel. When he is not writing, he enjoys cooking, amateur astronomy and going to Alton Towers.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Universe Versus Alex Woods

By Gavin ExtenceOrbit

All rights reserved.

CHAPTER 1

ENTENDER

They finally stopped me at Dover as I was trying to get back into the country. Iwas half expecting it, but it still came as kind of a shock when the barrierstayed down. It's funny how some things can be so mixed up like that. Havingcome this far, I'd started to think that I might make it the whole way homeafter all. It would have been nice to have been able to explain things to mymother. You know: before anyone else had to get involved.

It was 1 a.m., and it was raining. I'd rolled Mr Peterson's car up to the boothin the 'Nothing to Declare' lane, where a single customs officer was on duty.His weight rested on his elbows, his chin was cupped in his hands, and, but forthis crude arrangement of scaffolding, his whole body looked ready to fall likea sack of potatoes to the floor. The graveyard shift – dreary dull fromdusk till dawn – and for a few heartbeats it seemed that the customsofficer lacked the willpower necessary to rotate his eyeballs and check mycredentials. But then the moment collapsed. His gaze shifted; his eyes widened.He signalled for me to wait and spoke into his walkie-talkie, rapidly and withobvious agitation. That was the instant I knew for sure. I found out later thatmy picture had been circulated in every major port from Aberdeen to Plymouth.With that and the TV appeals, I never stood a chance.

What I remember next is kind of muddled and strange, but I'll try to describe itfor you as best I can.

The side door of the booth was swinging open and at the same moment there washedover me the scent of a field full of lilacs. It came on just like that, fromnowhere, and I knew straight away that I'd have to concentrate extra hard tostay in the present. In hindsight, an episode like this had been on the cardsfor a while. You have to bear in mind that I hadn't slept properly for severaldays, and Bad Sleeping Habits has always been one of my triggers. Stress isanother.

I looked straight ahead and I focussed. I focussed on the windscreen wipersmoving back and forth and tried to count my breaths, but by the time I'd got tofive, it was pretty clear that this wasn't going to be enough. Everything wasbecoming slow and blurry. I had no choice but to turn the stereo up to maximum.Handel's Messiah flooded the car – the 'Hallelujah' chorus, loudenough to rattle the exhaust. I hadn't planned it or anything. I mean, if I'dhad time to prepare for this, I'd have chosen something simpler and calmer andquieter: Chopin's nocturnes or one of Bach's cello suites, perhaps. But I'd beenworking my way through Mr Peterson's music collection since Zurich, and it justso happened that at that precise moment I was listening to that precisesection of Handel's Messiah – like it was Fate's funny joke. Ofcourse, this did me no favours later on: the customs officer gave a full reportto the police in which he said that for a long time I'd resisted detention, thatI'd just sat there 'staring into the night and listening to religious music atfull volume, like he was the Angel of Death or something'. You've probably heardthat quote already. It was in all the papers – they have a real boner fordetails like that. But you should understand that at the time I didn't have achoice. I could see the customs officer in my peripheral vision, hunchbacked atmy window in his bright yellow jacket, but I forced myself to ignore him. Heshone his torch in my eyes, and I ignored that too. I just kept staring straightahead and focussing on the music. That was my anchor. The lilacs were stillthere, trying their best to distract me. The Alps were starting to intrude– jagged, frosted memories, as sharp as needles. I swaddled them in themusic. I kept telling myself that there was nothing but the music. Therewas nothing but the strings and the drums and the trumpets, and all thosecountless voices singing out God's praises. I know in retrospect that I musthave looked pretty suspicious, just sitting there like that with my eyes glazedand the music loud enough to wake the dead. It must have sounded like I had theentire London Symphony Orchestra performing on the back seat. But what could Ido? When you get an aura that powerful, there's no chance of it passing of itsown accord: to be honest with you, there were several moments when I was righton the precipice. I was just a hair's breadth from convulsions.

But after a while, the crisis abated. Something slipped back into gear. I wasdimly aware that the torch beam had moved on. It was now frozen on the space twofeet to my left, though I was too frazzled to figure out why at the time. It wasonly later that I remembered Mr Peterson was still in the passenger seat. Ihadn't thought to move him.

The moments ticked on, and eventually the torchlight swung away. I managed toturn my head forty-five degrees and saw that the customs officer was againspeaking into his walkie-talkie, palpably excited. Then he tapped the torchagainst the window and made an urgent downwards gesture. I don't rememberpushing the button, but I do remember the rush of cold, damp air as the glassrolled down. The customs officer mouthed something, but I couldn't make it out.The next thing I knew, he'd reached through the open window and flipped off theignition. The engine stopped, and a second later, the last hallelujah died onthe night air. I could hear the hiss of drizzle on tarmac, fading in slowly,like reality resolving itself. The customs officer was speaking too, and wavinghis arms in all these weird, wobbly gestures, but my brain wasn't able to decodeany of that yet. Right then, there was something else going on – a thoughtthat was fumbling its way towards the light. It took me for ever to organize myideas into words, but when I finally got there, this is what I said: 'Sir, Ishould tell you that I'm no longer in a fit state to drive. I'm afraid you'llhave to find someone else to move the car for me.'

For some reason, that seemed to choke him. His face went through a whole seriesof strange contortions, and then for a very long time he just stood there withhis mouth open. If it had been me standing there with my mouth open, it wouldhave been considered pretty rude, but I don't think it's worth getting toouptight about things like that. So I just waited. I'd said what I needed to say,and it had taken considerable effort. I didn't mind being patient now.

When he'd cleared his airways, the customs officer told me that I had to get outof the car and come with him straight away. But the funny thing was, as soon ashe said it, I realized that I wasn't quite ready to move yet. My hands werestill locked white on the steering wheel, and they showed no signs ofrelinquishing their grip. I asked if I could possibly have a minute.

'Son,' the customs officer said, 'I need you to come now.'

I glanced across at Mr Peterson. Being called 'son' was not a good omen. Ithought I was probably in a Whole Heap of Shit.

My hands unlocked.

I managed to get out of the car, reeled and then leaned up against the side fora few seconds. The customs officer tried to get me to move, but I told him thatunless he wanted to carry me, he'd have to give me a moment to find my feet. Thedrizzle was prickling the exposed skin on my neck and face, and small tears ofrain were beginning to bead on my clothing. I could feel all my sensationsregrouping. I asked how long it had been raining. The customs officer looked atme but didn't reply. The look said that he wasn't interested in small talk.

A police car came and took me away to a room called Interview Room C in DoverPolice Station, but first I had to wait in a small Portakabin back in the mainpart of the port. I had to wait for a long time. I saw a lot of differentofficers from the Port Authority, but no one really talked to me. They just keptgiving me all these very simple two-word instructions, like 'wait here' and'don't move', and telling me what was going to happen to me next, like they werethe chorus in one of those Ancient Greek plays. And after every utterance,they'd immediately ask me if I understood, like I was some kind of imbecile orsomething. To be honest with you, I might have given them that impression. Idon't know. I still hadn't recovered from my seizure. I was tired, my co-ordination was shot, and on the whole I felt pretty disconnected, like my headhad been packed with cotton wool. I was thirsty too, but I didn't want to ask ifthere was a vending machine I might use in case they thought I was trying to beclever with them. As you probably know, when you're in trouble already, you canask a simple, legitimate question like that and end up in even more trouble. Idon't know why. It's like you cross this invisible line and suddenly peopledon't want to acknowledge that everyday things like vending machines or DietCoke exist any more. I guess some situations are supposed to be so grave thatpeople don't want to trivialize them with carbonated drinks.

Anyway, eventually a police car came and took me away to Interview Room C, wheremy situation was in no way improved. Interview Room C was not much larger than acupboard and had been designed with minimum comfort in mind. The walls and floorwere bare. There was a rectangular table with four plastic chairs, and a tinywindow that didn't look like it opened, high up on the back wall. There was asmoke alarm and a CCTV camera in one corner, close to the ceiling. But that wasit as far as furnishings were concerned. There wasn't even a clock.

I was seated and then left alone for what seemed like a very long time. I thinkmaybe that was deliberate, to try to make me feel restless or uncomfortable, butreally I've got no definite grounds for thinking that. It's just a hypothesis.Luckily, I'm very happy in my own company, and pretty adept at keeping my mindoccupied. I have about a million different exercises to help me stay calm andfocussed.

When you're tired but need to stay alert, you really need something a bit trickyto keep your mind ticking over. So I started to conjugate my irregular Spanishverbs, starting in the simple present and then gradually working my way throughto the more complicated tenses. I didn't say them aloud, because of the CCTVcamera, but I voiced them in my head, still taking care with the accent andstresses. I was on entiendas, the informal second-person presentsubjunctive of entender (to understand), when the door opened and twopolicemen walked in. One was the policeman who had driven me from the port, andhe was carrying a clipboard with some papers attached to it. The other policemanI hadn't seen before. They both looked pissed off.

'Good morning, Alex,' said the police officer whom I didn't know. 'I'm ChiefInspector Hearse. You've already met Deputy Inspector Cunningham.'

'Yes,' I said. 'Hello.'

I'm not going to bother describing Chief Inspector Hearse or Deputy InspectorCunningham for you at any great length. Mr Treadstone, my old English teacher,used to say that when you're writing about a person, you don't need to describeevery last thing about him or her. Instead, you should try to give just onetelling detail to help the reader picture the character. Chief Inspector Hearsehad a mole the size of a five-pence piece on his right cheek. Deputy InspectorCunningham had the shiniest shoes I've ever seen.

They sat down opposite, and gestured that I should sit down too. That was when Irealized that I'd stood up when they walked in the room. That's one of thethings they taught you at my school – to stand up whenever an adult entersthe room. It's meant to demonstrate respect, I guess, but after a while, youjust do it without thinking.

They looked at me for quite a long time without saying anything. I wanted tolook away, but I thought that might seem rude, so I just kept looking straightback and waited.

'You know, Alex,' Chief Inspector Hearse said finally, 'you've created quite astir over the past week or so. You've become quite the celebrity ...'

Straight away, I didn't like the way this was going. I had no idea what heexpected me to say. Some things there's no sensible response to, so I just keptmy mouth shut. Then I shrugged, which wasn't the cleverest thing to do, but it'svery difficult to do nothing in situations like that.

Chief Inspector Hearse scratched his mole. Then he said: 'You realize thatyou're in a lot of trouble?'

It might have been a question; it might have been a statement. I nodded anyway,just in case.

'And you know why you're in trouble?'

'Yes. I suppose so.'

'You understand that this is serious?'

'Yes.'

Chief Inspector Hearse looked across at Deputy Inspector Cunningham, who hadn'tsaid anything yet. Then he looked at me again. 'You know, Alex, some of youractions over the past hour suggest otherwise. I think if you realized howserious this was, you'd be a lot more worried than you appear to be. Let me tellyou, if I was sitting where you are now, I think I'd be a lot more worried thanyou appear to be.'

He should have said 'if I were sitting where you are now' – Inoticed because I already had the subjunctive on my mind – but I didn'tcorrect him. People don't like to be corrected about things like that. That wasone of the things Mr Peterson always told me. He said that correcting people'sgrammar in the middle of a conversation made me sound like a Major Prick.

'Tell me, Alex,' Chief Inspector Hearse went on, 'are you worried? Youseem a little too calm – a little too casual – all thingsconsidered.'

'I can't really afford to let myself get too stressed out,' I said. 'It's notvery good for my health.'

Chief Inspector Hearse exhaled at length. Then he looked at Deputy InspectorCunningham and nodded. Deputy Inspector Cunningham handed him a sheet of paperfrom the clipboard.

'Alex, we've been through your car. I think you'll agree that there are severalthings we need to discuss.'

I nodded. I could think of one thing in particular. But then Chief InspectorHearse surprised me: he didn't ask what I thought he was going to ask. Instead,he asked me to confirm, as a matter of record, my full name and date of birth.That threw me for about a second. All things considered, it seemed like a wasteof time. They already knew who I was: they had my passport. There was no reasonnot to cut to the chase. But, really, I didn't have much choice but to go alongwith whatever game they were playing.

'Alexander Morgan Woods,' I said. 'Twenty-third of the ninth, 1993.'

I'm not too enamoured with my full name, to be honest with you, especially themiddle part. But most people just call me Alex, like the policemen did. Whenyou're called Alexander, hardly anyone bothers with your full name. My motherdoesn't bother. She goes one syllable further than everyone else and just callsme Lex, as in Lex Luthor – and you should know that she was calling methat long before I lost my hair. After that, I think she started to regard myname as prophetic; before, she just thought it was sweet.

Chief Inspector Hearse frowned and then looked at Deputy Inspector Cunninghamagain and nodded. He kept doing that, like he was the magician and DeputyInspector Cunningham was his assistant with all the props.

Deputy Inspector Cunningham took from the back of his clipboard a clear plasticbag, which he then tossed into the centre of the table, where it landed with aquiet slap. It was extremely dramatic, it really was. And you could tell thatthey wanted it to be dramatic. The police have all sorts ofpsychological tricks like that. You probably know that already if you ever watchTV.

'Approximately one hundred and thirteen grams of marijuana,' Chief InspectorHearse intoned, 'retrieved from your glove compartment.'

I'm going to level with you: I'd completely forgotten about the marijuana. Thefact is, I hadn't even opened the glove compartment since Switzerland. I'd hadno reason to. But you try telling the police something like that at around 2a.m. when you've just been stopped at customs.

'That's a lot of pot, Alex. Is it all for personal use?'

'No ...' I changed my mind. 'Actually, yes. I mean, it was for personal use, butnot for my personal use.'

Chief Inspector Hearse raised his eyebrows about a foot. 'You're saying thatthis one hundred and thirteen grams of marijuana isn't for you?'

(Continues...)

Excerpted from The Universe Versus Alex Woods by Gavin Extence. Copyright © 2014 Gavin Extence. Excerpted by permission of Orbit.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Gratis für den Versand innerhalb von/der USA

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenEUR 28,75 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für The Universe Versus Alex Woods

The Universe Versus Alex Woods

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.22. Artikel-Nr. G0316246573I3N10

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Universe Versus Alex Woods

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.22. Artikel-Nr. G0316246573I2N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Universe Versus Alex Woods

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.22. Artikel-Nr. G0316246573I4N10

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Universe Versus Alex Woods

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 4049711-75

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Universe Versus Alex Woods

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. GOR007236404

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Universe Versus Alex Woods

Anbieter: medimops, Berlin, Deutschland

Zustand: good. Befriedigend/Good: Durchschnittlich erhaltenes Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit Gebrauchsspuren, aber vollständigen Seiten. / Describes the average WORN book or dust jacket that has all the pages present. Artikel-Nr. M00316246573-G

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Universe Versus Alex Woods

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Hardcover. Zustand: Brand New. june 25, 2013 edition. 416 pages. 9.00x6.00x1.00 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. 0316246573

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar