Inhaltsangabe

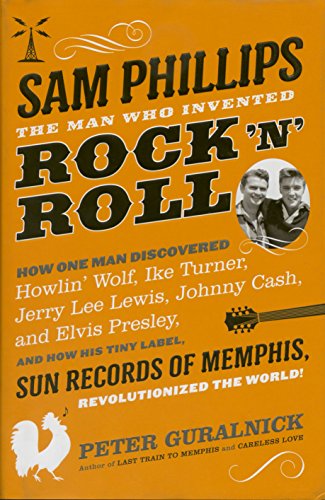

The music that he shaped in his tiny Memphis studio with artists as diverse as Elvis Presley, Ike Turner, Howlin' Wolf, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Johnny Cash, introduced a sound that had never been heard before. He brought forth a singular mix of black and white voices passionately proclaiming the vitality of the American vernacular tradition while at the same time declaring, once and for all, a new, integrated musical day.

With extensive interviews and firsthand personal observations extending over a 25-year period with Phillips, along with wide-ranging interviews with nearly all the legendary Sun Records artists, Guralnick gives us an ardent, unrestrained portrait of an American original as compelling in his own right as Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, or Thomas Edison.

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll was named Best Blues Book of the Year (Living Blues), Best Book on Country Music (by Belmont University’s International Country Music Conference), and was a finalist for the Plutarch Award for Best Biography of the Year, awarded by the Biographers International Organization.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Peter Guralnick's books include the prize-winning two-volume biography of Elvis Presley, Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love. He is a recent inductee in the Blues Hall of Fame. Other books include an acclaimed trilogy on American roots music, Sweet Soul Music, Lost Highway, and Feel Like Going Home; the biographical inquiry Searching for Robert Johnson; the novel, Nighthawk Blues, and Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke. His most recent book is Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Sam Phillips

The Man Who Invented Rock 'N' Roll

By Peter GuralnickLittle, Brown and Company

All rights reserved.

Contents

Cover,

Disclaimer,

Also by Peter Guralnick,

Title Page,

Copyright,

Dedication,

Author's Note,

1 | "I Dare You!" 1923–1942,

2 | Radio Romance 1942–1950,

3 | The Price of Freedom January 1950–June 1951,

4 | "Where the Soul of Man Never Dies" June 1951–October 1952,

5 | Perfect Imperfection June 1952–July 1953,

6 | Prisoner's Dream July 1953–February 1955,

7 | Spiritual Awakenings January 1955–December 1956,

8 | I'll Sail My Ship Alone 1957–1961,

9 | "They'll Carry You to the Cliff and Shove You Off" 1979–1961–1979,

10 | How Lucky Can One Man Get 1980–2003,

Notes,

Bibliography,

A Brief Discographical Note,

Acknowledgments,

Index,

CHAPTER 1

"I Dare You!"

Nothing passed my ears. A mockingbird or a whippoorwill — out in the country on a calm afternoon. The silence of the cottonfields, that beautiful rhythmic silence, with a hoe hitting a rock every now and then and just as it spaded through the dirt, you could hear it. That was just unbelievable music: to hear that bird maybe three hundred yards away, the wind not even blowing in your direction, or no wind at all. But it carried, it got to my ears. I would hear somebody speak to a mule harshly, I heard that. I mean, I heard everything. It wasn't any time until I began to observe people [too], more by sound — I certainly didn't know what to do with everything I heard, but I knew I had something that could be an asset if I could just figure out what to do with it.

In later years Sam Phillips would always refer to the moment of his arrival on this earth with a wonderment not altogether free of caustic amusement. "You take my ass dying when I was born, and you take a drunk doctor showing up — man, he didn't even make it till I was born — and my mama being so kind she got up out of bed and put him to bed until he sobered up, and then the midwife comes and Mama feels so sorry for Dr. Cornelius she named me after him!"

Nobody ever took more pleasure in his own story than Sam Phillips. It was, in his telling, a poetic as much as a realistic vision, a mythic journey combining narrative action, revolutionary rhetoric, Delphic pronouncements, and the satisfaction, like that of any Old Testament god, of being able to look back on the result and pronounce it "good." He would return again and again to the same themes over the years, with different details and different emphases, but always with the same underlying message: the inherent nobility not so much of man as of freedom, and the implied responsibility — no, the obligation — for each of us to be as different as our individuated natures allowed us to be. To be different, in Sam's words, in the extreme.

But it always started out with a slight, sickly looking tow-headed little boy looking out at the world from the 323-acre farm at the Bend of the River, about ten miles outside Florence, Alabama. His daddy didn't own the farm, just rented it, and by the time Sam was eight years old, his two oldest brothers and older sister had all married, leaving him at home with his seventeen-year-old sister, Irene, his fifteen-year-old-brother, Tom, and the next youngest, ten-year-old J.W. (John William, later to be known as Jud), who was, like Sam, something of an afterthought for parents who were forty-four and nearly forty by the time their youngest child was born.

He and his family worked the fields with mules, along with dozens of others, black and white sharecroppers, poor people — his daddy was a fair man, he treated them all the same. His daddy didn't say much; the one thing that really made him mad was if someone told him a lie — it didn't matter who it was, he would stand up and tell them to their face. Daddy had a feel for the land, he grew corn, hay, and sweet sorghum, and the cotton rows were half a mile long. His mama was kind to everyone, believed wholeheartedly in all her children, and worried a lot — there was nothing she wouldn't do for any of them, and nothing she couldn't do as well as any man. Sometimes at night she might dip a little snuff and pick the guitar, old folk songs like "Barbara Allen" and "Aura Lee," the guitar took on all the properties of a human voice, but she didn't sing, it was almost as if she were quilting the music together.

Just like Daddy, she taught them how to work, by her example. She taught them responsibility by the kindness she and Daddy showed to others less fortunate, including relatives, passing strangers, and, by the presence in their own home, her sister Emma, blinded in one eye and made deaf and mute by Rocky Mountain spotted fever when she was three. Sam observed Aunt Emma closely and, in order to communicate with her (she was a well-educated woman, a graduate of the internationally renowned Alabama Institute for Deaf and Blind at Talladega), learned to sign almost before he could read. He was the only one in the family who could communicate fully with her except for Mama and his sister Irene, who wanted to become a nurse. Even when he was working (and there was seldom a time that he wasn't), he was watching, listening, observing: the interactions of people, the scudding of the clouds across the sky, the communication of crickets and frogs (he was convinced that he could talk to them — and not just as a little boy either), the flow of the beautiful Tennessee River. He couldn't understand why all the little black boys and girls he worked and played with couldn't go to the same little country school that he did; he registered the unfairness of the way in which people were arbitrarily set apart by the color of their skin, and he thought, What if I had been born black? And he admired the way they dealt with adversity — he envied them their power of resilience, their ability to maintain belief in a situation in which he doubted he could have sustained belief himself. But, for the most part, knowing how different his feelings were even from those closest to him, from his very family, and knowing how much more different he intended to be, he kept his thoughts to himself and listened to the a cappella singing that came from the fields, testament as he saw it, whether sacred or secular, to an invincible human spirit and spirituality.

They found a way to worship. You could hear it. You could feel it. You didn't have to be inside a building, you could participate in a cotton patch, picking four rows at a time, at 110 degrees! I mean, I saw the inequity. But even at five or six years old I found myself caught up in a type of emotional reaction that was, instead of depressing — I mean, these were some of the astutest people I've ever known, and they were in [most] cases almost totally overlooked, except as a beast of burden — but even at that age, I recognized that: Hey! The backs of these people aren't broken, they [can] find it in their souls to live a life that is not going to take the joy of living away.

Samuel Cornelius Phillips (remember Dr. Cornelius) was born on January 5, 1923, in the only home that his father would ever own, in a tiny hamlet six or seven miles north of Florence called Lovelace Community, named for his mother's family and populated with musically...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n'...

Sam Phillips: the Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. First Edition. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 7751085-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: the Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. First Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 11189734-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: the Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. First Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 11189734-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: the Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. First Edition. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Artikel-Nr. 5696221-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. Good dust jacket. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Artikel-Nr. O09N-00285

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. Like New dust jacket. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. V02B-05357

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0316042749I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0316042749I4N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0316042749I3N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0316042749I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar