Inhaltsangabe

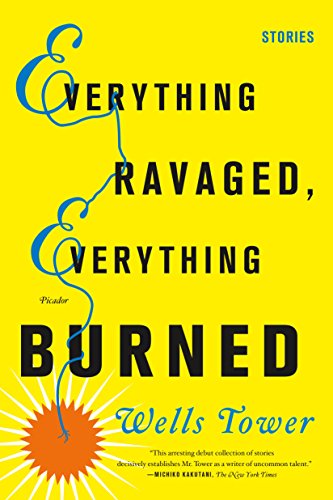

In Tower's debut collection of stories, families fall apart and messily try to reassemble themselves in an America that is touched by the seamy splendor of the dropout, the misfit, boozy dreamers, hapless fathers, and wayward sons.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Wells Tower

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned

StoriesBy Wells TowerPicador

Copyright © 2010 Wells TowerAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780312429294

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Artikel-Nr. F06D-01636

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. 1 Reprint. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 4107399-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1 Reprint. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 5748792-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1 Reprint. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 4107399-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 5 verfügbar

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0312429290I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0312429290I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0312429290I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0312429290I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned: Stories

Anbieter: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, USA

paperback. Zustand: Good. First Edition. first edition. Artikel-Nr. mon0003237444

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

EVERYTHING RAVAGED, EVERYTHING BURNED

Anbieter: Magers and Quinn Booksellers, Minneapolis, MN, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. May have light to moderate shelf wear and/or a remainder mark. Complete. Clean pages. Artikel-Nr. 44291

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar