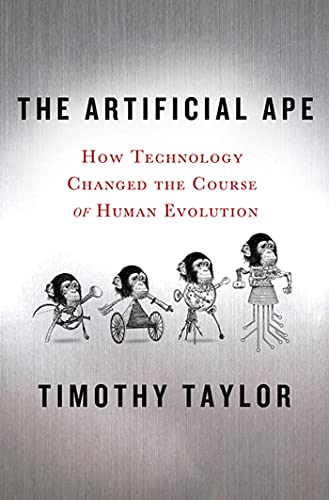

The Artificial Ape: How Technology Changed the Course of Human Evolution (MacSci) - Hardcover

Buch 10 von 24: MacSci

Inhaltsangabe

One of the enduring mysteries of human origins is how our ancestors separated from the other great apes and set out on a different evolutionary path: they began to walk upright, lost their body hair, and grew significantly larger brains. These new physical traits changed us so much that we could no longer exist in the wild with our primate cousins without special protection. While Darwin's theory explains our common descent, scientists are grappling with the reasons why human evolution defies the principles of natural selection and why, although we dominate the planet, we have become the weakest ape. In this fascinating narrative, leading archeologist Timothy Taylor proposes that it was our early adoption of tools, objects, and, now, technology that changed us, demonstrating how:

Baby slings made out of animal fur freed up our arms up to use tools

Clothes kept us warm reducing our need for body hair

Shelter protected us from the elements and led our bodies to become slighter and physically weaker

Fire enabled us to cook which changed the make up of our stomachs

Drawing on the latest fossil evidence Taylor argues, that every step of the way, humans made choices that assumed greater control over their own evolution. This is a process that continues today as we push the frontiers of scientific technology, creating prosthetics and implants that integrate seamlessly into our bodies creating a new form of artificial humans.

A breakthrough theory that tools and technology are the real drivers of human evolution.

Although humans are one of the great apes, along with chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, we are remarkably different from them. Unlike our cousins who subsist on raw food, spend their days and nights outdoors, and wear a thick coat of hair, humans are entirely dependent on artificial things, such as clothing, shelter, and the use of tools, and would die in nature without them. Yet, despite our status as the weakest ape, we are the masters of this planet. Given these inherent deficits, how did humans come out on top?

In this fascinating new account of our origins, leading archaeologist Timothy Taylor proposes a new way of thinking about human evolution through our relationship with objects. Drawing on the latest fossil evidence, Taylor argues that at each step of our species' development, humans made choices that caused us to assume greater control of our evolution. Our appropriation of objects allowed us to walk upright, lose our body hair, and grow significantly larger brains. As we push the frontiers of scientific technology, creating prosthetics, intelligent implants, and artificially modified genes, we continue a process that started in the prehistoric past, when we first began to extend our powers through objects.

Weaving together lively discussions of major discoveries of human skeletons and artifacts with a reexamination of Darwin's theory of evolution, Taylor takes us on an exciting and challenging journey that begins to answer the fundamental question about our existence: what makes humans unique, and what does that mean for our future?

A new take on the evolutionary story as archaeological evidence unravels the great mystery of why human evolution defies the principles of natural selection

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Timothy Taylor, PhD is the author of The Buried Soul and The Prehistory of Sex. He has appeared on the History Channel, the Discovery Channel, and National Geographic specials. He contributes to such publications as Nature, Scientific American, and World Archaeology, and is editor-in-chief of the Journal of World Prehistory. He teaches archaeology at the University of Bradford in the United Kingdom.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Artificial Ape

How Technology Changed the Course of Human Evolution

By Timothy TaylorPalgrave Macmillan

All rights reserved.

Contents

Introduction: Just Three Systems,

1 Survival of the Weakest,

2 Naked Cunning,

3 Unintelligent Design,

4 The 7,000-Calorie Lunch,

5 The Smart Biped Paradox,

6 Inward Machinery,

7 Skeuomorphs,

8 Screen Culture,

Conclusion: One World, Again,

Acknowledgments,

Notes,

Bibliography,

Index,

CHAPTER 1

SURVIVAL OF THE WEAKEST

A fox (canis fulvipes), of a kind said to be peculiar to the island, and very rare in it, and which is a new species, was sitting on the rocks. He was so intently absorbed in watching the work of the officers, that I was able, by quietly walking up behind, to knock him on the head with my geological hammer.

—Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches, December 6, 1834

IN THE HIGH ALPS a 5,000-year-old frozen corpse, "Ötzi the Ice Man," lay beside his longbow. The axe marks had not been smoothed off, but the functional aspects were complete—it was a replacement weapon, made in haste. We know he was a man in a hurry: sophisticated forensic archaeological analysis has revealed his story, from the sequence of inhaled tree pollens in his lungs, characteristic of different altitudes, to his stomach contents and the scans that show a rib broken only days before death. He had, my Austrian colleagues are now convinced, been on the run, up mountains and down valleys, for several days, living rough, pursued, desperate to rearm himself, and finally driven toward a high mountain pass with a blizzard threatening. There he was shot in the back from a distance by an expert. Still running, he reached back to grasp the shaft where it projected beneath his shoulder blade; it snapped, leaving the flint arrowhead lodged. The internal bleeding was unstoppable, and by now out of sight of his enemies, he collapsed into the first heavy snow of winter and died. Ice closed over him, and he vanished from memory until 1991, when global warming, acting on the Ötztal glacier, melted him back into view. By the time of Ötzi's death, in the later Neolithic period around 3300 B.C., human beings had long been the planet's top predator, fearing mostly each other.

Before Ötzi died, he had been a farmer who, from time to time, also hunted. He was part of a wave of colonization and economic change that had been sweeping into central Europe from the Balkans (and ultimately western Asia) since 5500 B.C. His ancestors had carved out territory in a zone previously dominated by dedicated wilderness dwellers. These were people who had never had domestic animals or fenced off land. They were mobile and innovative bands of men, women, and children who hunted, fished, and gathered. Their communities had expanded rapidly into the burgeoning new forests of Europe around 10,000 years ago, after the ice sheets receded and the climate quickly warmed. These Mesolithic people were in turn descended from big-game hunters whose lineage can be traced back to a time when mammoth-hunting scenes were painted on cave walls.

This period, the Upper Paleolithic, was when the previous lords of Europe, the Neanderthals, were being squeezed out by our kind, anatomically modern Homo sapiens, first arriving from the Near East around 40,000 years ago. Neanderthals had weathered successive periods of advancing and retreating ice over the previous quarter of a million years. Before them had been Homo heidelbergensis, and, yet further back, Homo erectus. The sequence of kinds of humans, and kinds of human culture, arriving in waves over the hundreds of millennia before Ötzi's death is at least as complex as the history of Europe since that date. To understand how Ötzi (and we) came to look physically modern, to be able to think intelligently and make use of tools and weapons, we will have to track back far earlier, to a point even before there were humans.

* * *

I am unconvinced by the current understanding of our evolution— not whether or when evolutionary changes took place, but how and why. Like my academic colleagues, I have no doubt that humans emerged over vast spans of time, that our distant ancestors were apes, and that we are biological creatures. The results of each new field season of research in paleoanthropology—a new pelvis from Ethiopia, a different sort of small-headed Homo erectus from the high Caucasus Mountains, a new, very early tree-living ape that might be placed on or off our direct ancestral line according to highly technical arguments and scholarly taste—important as they are, do not change the basic fact that humans evolved from apes.

This simple fact is often misunderstood: "If we evolved from chimpanzees, then why are there still chimpanzees?" asked one child, after an introductory lecture I had given his school class, sure that he had spotted the killer weakness in the evolution argument. The answer, of course, is that we didn't. Chimpanzees have evolved alongside us since a point, maybe 7 million years ago, when we formed a single breeding community of some kind of ape. That ape, whatever it was, was much more like a chimpanzee than like us, and that means that modern chimpanzees have not evolved as dramatically as we have. One group of apes continued doing what they had been doing pretty successfully. They may have moved down from trees more, and evolved knuckle-walking, but they never walked fully upright. They kept their insulating fur, never finding a need for clothes, never freeing up their hands to make them, or developing brains large enough to think of them. The other group, split off perhaps by a simple fact of geography, got embroiled in something else. What happened to them was very different and very varied: before we emerged as the only surviving upright-walking ape, there were numerous prototypes, most of them evolutionary dead ends.

Darwin had no access to the African fossil record—he suspected it might exist, but he did not live long enough to see even the first finds. But he did apply some smart thinking to the living species of ape he knew about. He considered it significant that two kinds of great ape— gorillas and chimpanzees (two species of each are now recognized)— lived in the wild in Africa while only one—the orangutan (also now divided into two species)—lived wild outside it, in southeast Asia. Using the same logic he had applied to the evolution of birds and fish, Darwin argued that Africa, as home to the most kinds of great ape, should be the continent on which the common ancestor of apes and humans had lived. He predicted, in advance of the fossil evidence, that it would be there that any intermediate "missing links" would be discovered.

Darwin upheld his African origin theory even after the discovery of the first Neanderthal skeleton in Germany, believing (correctly, as it turns out) that Neanderthals were relatively modern, being a parallel line of later human evolution and not an intermediate link with apes. It was nearly a decade after Darwin's death that the first physical evidence for a missing link came to light, at Trinil in Java. Although "Java Man," now classified as Homo erectus, was, like the orangutan, also outside Africa, paleontological fieldwork throughout the twentieth century and up to the present shows that the most significant phases of human...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Suchergebnisse für The Artificial Ape: How Technology Changed the Course...

The Artificial Ape : How Technology Changed the Course of Human Evolution

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 5302808-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Artificial Ape : How Technology Changed the Course of Human Evolution

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. GRP70742608

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Artificial Ape

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0230617638I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Artificial Ape

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0230617638I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Artificial Ape

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0230617638I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Artificial Ape

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0230617638I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Artificial Ape

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0230617638I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Artificial Ape

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0230617638I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Artificial Ape : How Technology Changed the Course of Human Evolution

Anbieter: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. 5302808-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Artificial Ape : How Technology Changed the Course of Human Evolution

Anbieter: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. 1st Edition. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Artikel-Nr. GRP70742608

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar