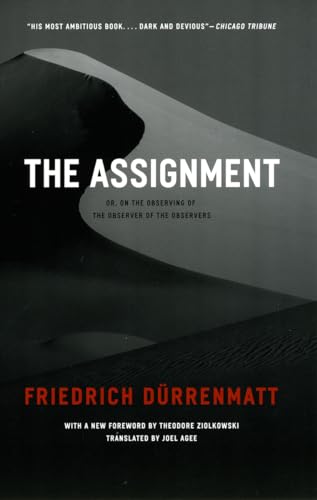

The Assignment: or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers: Or, on the observing of the observe of the observers. With a new foreword by Theodore Zidlkowski (Heritage of Sociology) - Softcover

Inhaltsangabe

In Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s experimental thriller The Assignment, the wife of a psychiatrist has been raped and killed near a desert ruin in North Africa. Her husband hires a woman named F. to reconstruct the unsolved crime in a documentary film. F. is soon unwittingly thrust into a paranoid world of international espionage where everyone is watched—including the watchers. After discovering a recent photograph of the supposed murder victim happily reunited with her husband, F. becomes trapped in an apocalyptic landscape riddled with political intrigue, crimes of mistaken identity, and terrorism.

F.’s labyrinthine quest for the truth is Dürrenmatt’s fictionalized warning against the dangers of a technologically advanced society that turns everyday life into one of constant scrutiny. Joel Agee’s elegant translation will introduce a fresh generation of English-speaking readers to one of European literature’s masters of language, suspense, and dystopia.

“The narrative is accelerated from the start. . . . As the novella builds to its horripilating climax, we realize the extent to which all values have thereby been inverted. The Assignment is a parable of hell for an age consumed by images.”—New York Times Book Review

“His most ambitious book . . . dark and devious . . . almost obsessively drawn to mankind’s most fiendish crimes.”—Chicago Tribune

“A tour-de-force . . . mesmerizing.”—Village Voice

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Joel Agee has translated numerous German authors into English, including Heinrich von Kleist, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Elias Canetti. In 2005 he received the Modern Language Association’s Lois Roth Award for his translation of Hans Erich Nossack’s The End: Hamburg 1943.

Theodore Ziolkowski is the Class of 1900 Professor Emeritus of German and Comparative Literature at Princeton University. He is the author of many books, including The Mirror of Justice: Literary Reflections of Legal Crises.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Assignment, or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers

By Friedrich Dürenmatt, Joel AgeeThe University of Chicago Press

All rights reserved.

When Otto von Lambert was informed by the police that his wife Tina had been found dead and violated at the foot of the Al-Hakim ruin, and that the crime was as yet unsolved, the psychiatrist, well known for his book on terrorism, had the corpse transported by helicopter across the Mediterranean, suspended in its coffin by ropes from the bottom of the plane, so that it trailed after it slightly, over vast stretches of sunlit land, through shreds of clouds, across the Alps in a snowstorm, and later through rain showers, until it was gently reeled down into an open grave surrounded by a mourning party, and covered with earth, whereupon von Lambert, who had noticed that F., too, had filmed the event, briefly scrutinized her and, closing his umbrella despite the rain, demanded that she and her team visit him that same evening, since he had an assignment for her that could not be delayed.

CHAPTER 2F., well known for her film portraits, who had resolved to explore new paths and was pursuing the still vague idea of creating a total portrait, namely a portrait of our planet, by combining random scenes into a whole, which was the reason why she had filmed the strange burial, stood staring after the massively built man, von Lambert, who, drenched and unshaven, had accosted her, and had turned his back on her without greeting, and she decided only after some hesitation to do what he had asked, for she had an unpleasant feeling that something was not right, and that besides, she was running the danger of being drawn into a story that would deflect her from her plans, so that it was with a feeling of repugnance that she arrived with her crew at the psychiatrist's house, impelled by curiosity about the nature of his offer but determined to refuse whatever it was.

CHAPTER 3Von Lambert received her in his studio, demanded to be immediately filmed, willingly submitted to all the preparations, and then, sitting behind his desk, explained to the running camera that he was guilty of his wife's death because he had always treated the heavily depressed woman as a case instead of as a person, until she had accidentally discovered his notes on her sickness and, according to the maid, left the house straight away, a red fur coat thrown over her denim suit, clutching her pocketbook, after which he had not heard from her at all, but neither had he undertaken to learn her whereabouts, if only to grant her whatever freedom she desired, or, on the other hand, should she discover his investigations, to spare her the feeling that she was being watched from a distance, but now that she had come to such a terrible end he was forced to recognize his guilt not only in having treated her with the cool scrutiny prescribed by psychoanalytic practice but also in having failed to investigate her disappearance, he regarded it as his duty to find out the truth, and beyond that, to make it available to science, since his wife's fate had brought him up against the limits of his profession, but since he was a physical wreck and not capable of taking the trip himself, he was giving her, F., the assignment of reconstructing the murder (of which he as her doctor was the primary cause, the actual perpetrator being but an accidental factor) at the apparent scene of the crime, of recording whatever was there to be recorded, so that the results could be shown at psychoanalytic conferences and presented to the state prosecutor's office, since, being guilty, he, like any criminal, had lost the right to keep his failure secret, and having said this, he handed her a check for a considerable sum of money, several photographs of the murdered woman, her journal, and his notes, whereupon F., much to the surprise of her crew, accepted the assignment.

CHAPTER 4After leaving the psychiatrist's house, F. refused to answer her cameraman's question as to the meaning of all this nonsense, spent most of the night perusing the journal and the doctor's notes, and, after a brief sleep, still in bed, made arrangements with a travel agency for the flight to M., drove into town, bought several newspapers with pictures of the strange funeral and the dead woman on their front pages, and, before checking a hastily scribbled address she had found in the journal, went to an Italian restaurant for breakfast, where she encountered the logician D., whose lectures at the university were attended by two or three students — an eccentric and sharp-witted man of whom no one could tell whether he was unfit for life or merely pretended to be helpless, who expounded his logical problems to anyone who joined him at his table in the always crowded restaurant, and this in such a confused and thoroughgoing manner that no one was able to understand him, not F. either, though she found him amusing, liked him, and often told him about her plans, as she did now, mentioning first the peculiar assignment she had been given, and going on to talk about the dead woman's journal, as if to herself, unconscious of her interlocutor, so preoccupied was she by that densely filled notebook: never, she said, never in her life had she read a similar description of a person, Tina von Lambert had portrayed her husband as a monster, but gradually, not immediately, virtually peeling off pieces of him, facet by facet, examining each one separately, as if under a microscope, constantly narrowing and magnifying the focus and sharpening the light, page after page about his eating habits, page after page about the way he picked his teeth, page after page about how and where he scratched himself, page after page about his coughing or sneezing or clearing his throat or smacking his lips, his involuntary movements, gestures, twitches, idiosyncrasies more or less common to most people, but described in such a way that she, F., had a hard time contemplating the subject of food now, and if she had not touched her breakfast yet, it was only because she could not help imagining that she herself was disgusting to look at while eating, for it was impossible to eat aesthetically, and reading this journal was like being immersed in a cloud of pure observations gradually condensing into a lump of hate and revulsion, or like reading a film script for a documentary of every human being, as if every person, if he or she were filmed in this manner, would turn into a von Lambert as he was described by this woman, all individuality crushed out by such ruthless observation, while F.'s own impression of the psychiatrist had been one of a fanatic who was beginning to doubt his cause, extraordinarily childlike and helpless in a way that reminded her of many scientists, a man who had always believed and still believed that he loved his wife, and to whom it had never occurred that it was all too easy to imagine that one loved someone, and that basically one loved only oneself, but even before meeting him, the spectacular funeral had made her suspect that its purpose was to cover up his hurt pride, why not, and as for the assignment to hunt for the circumstances of her death, he was probably trying, albeit unconsciously, to build a monument to himself, and if Tina's description of her husband was grotesque in its exaggeration and excessive concreteness, von Lambert's notes were equally grotesque in their abstraction, they weren't observations at all but literally an abstracting of her humanity, defining depression as a psychosomatic phenomenon resulting from insight into the meaninglessness of existence, which is...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für The Assignment: or, On the Observing of the Observer...

The Assignment: or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers (Heritage of Sociology)

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. P16D-01732

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Assignment: or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0226174468I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Assignment: or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0226174468I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Assignment: or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0226174468I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Assignment: or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers (Heritage of Sociology)

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. GOR003954540

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Assignment: or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers: Or, on the Observing of the Observer of the Observed (Heritage of Sociology)

Anbieter: medimops, Berlin, Deutschland

Zustand: very good. Gut/Very good: Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit wenigen Gebrauchsspuren an Einband, Schutzumschlag oder Seiten. / Describes a book or dust jacket that does show some signs of wear on either the binding, dust jacket or pages. Artikel-Nr. M00226174468-V

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Assignment or, On the Oberserving of the Observer of the Observed

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. revised ed. edition. 152 pages. 7.75x5.50x0.50 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. x-0226174468

Neu kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Assignment

Anbieter: moluna, Greven, Deutschland

Kartoniert / Broschiert. Zustand: New. The wife of a psychiatrist has been raped and killed near a desert ruin in North Africa. Her husband hires a woman named F to reconstruct the unsolved crime in a documentary film. F is soon thrust into a paranoid world of international espionage where every. Artikel-Nr. 350932078

Neu kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar

The Assignment - or, On the Observing of the Observer of the Observers; . : Or, on the observing of the observe of the observers. With a new foreword by Theodore Zidlkowski

Anbieter: AHA-BUCH GmbH, Einbeck, Deutschland

Taschenbuch. Zustand: Neu. Neuware - The wife of a psychiatrist has been raped and killed near a desert ruin in North Africa. Her husband hires a woman named F to reconstruct the unsolved crime in a documentary film. F is soon thrust into a paranoid world of international espionage where everyone is watched - including the watchers. Artikel-Nr. 9780226174464

Neu kaufen

Versand von Deutschland nach USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar