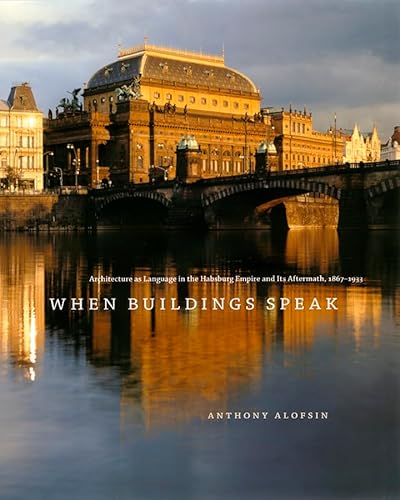

When Buildings Speak: Architecture as Language in the Habsburg Empire and Its Aftermath, 1867-1933 (Emersion: Emergent Village resources for communities of faith) - Softcover

Inhaltsangabe

&;The book itself as a production is spectacular.&;&;David Dunster, Architectural Review

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

When Buildings Speak

Architecture as Language in the Habsburg Empire and Its Aftermath, 1867–1933By ANTHONY ALOFSINThe University of Chicago Press

Copyright © 2006 Anthony AlofsinAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-226-01507-1

Contents

Preface.......................................................................................ixINTRODUCTION Issues of Architecture, Language, and Identity...................................11 The Language of History.....................................................................172 The Language of Organicism..................................................................553 The Language of Rationalism.................................................................814 The Language of Myth........................................................................1275 The Language of Hybridity...................................................................177CONCLUSION Continuities, Discontinuities, and Transformations.................................231Appendix: Place-Names, Educational Institutions, Translation of Secession.....................265Notes.........................................................................................267Selected Bibliography.........................................................................295Illustration Credits..........................................................................311Index.........................................................................................313

Chapter One

FROM THE outset, Austria and much of what would become the Austro-Hungarian Empire confronted foreign architectural idioms that it either copied or transformed for its own purposes. The process began when the area became a part of the Roman Empire, and the classical tradition provided early, if rudimentary, models for buildings and city forms, including Vindobona, the settlement that would become Vienna. After the fifth century, Germanic tribes occupied the area, and it eventually became a frontier in the empire of Charlemagne, a duchy and, in 1282, the seat of the Habsburg dynasty. Gothic architecture, with origins in France and variations from German states, provided other models, particularly for churches. Later, classical architecture, filtered through the Renaissance but more important through baroque architecture, eventually became the official imperial style.While architects and their patrons transformed the models of Italian baroque and French Gothic, cultural undercurrents from the East surrounded them. The residue of Celtic invasions, the exoticism of Asia, and the resonance of Islamic architecture spread over centuries of Turkish control of the southeast sector of the region, and pockets of folk and native traditions from the Carpathian Mountains to the Tyrol formed part of the heritage and culture. Furthermore, from the early nineteenth century, the emergence of industry and expanded commerce altered society. Official architecture still relied on a narrow selection of historical styles, but after 1850, architects and critics increasingly asked: was the language of history alive enough to express a variety of emerging meanings and identities? The answers are complex and paradoxical.

While many buildings could represent the paradoxical use of the language of history, Friedrich von Schmidt's Rathaus (city hall) in Vienna, Josef Zítek's Czech National Theater in Prague, and Otto Wagner's Rumbach Street Synagogue in Budapest not only provide a range of civic, cultural, and religious buildings, but show depth and complexity. The Rathaus invokes a tension between religion and government, city and empire; the theater appropriates historical idioms of neo-Renaissance architecture to represent national identity; and the synagogue shows Otto Wagner, a pivotal figure, early in his career as he begins to transform history into a modern idiom while engaging the question of defining religious identity with forms borrowed from diverse cultures.

WHILE THE Gothic mode had provided models for earlier buildings, particularly religious ones in Austria, the neo-Gothic revival affecting architecture in western Europe throughout the nineteenth century had limited appeal, as preference for neoclassical styles and the Baroque remained dominant. So it was unexpected when, in 1869, the City of Vienna used Gothic architecture as a language of history for the design of its new city hall, the Rathaus (fig. 1.1). After the revolution of 1848, the middle class established itself as a powerful political and economic entity whose multiple needs for a comprehensive new bureaucratic government made the old city hall too small. To provide a home for the practical and ceremonial functions of the government of Vienna and all of its councils, departments, and agencies, a new building was needed.

The location of the new Rathaus would be somewhere on the Ringstrasse, the urban thoroughfare created in the 1850s and 1860s on the recently demolished old city walls. Its exact site, however, was determined only after much political and financial struggle, which yielded the decision to build on a roomy site at the former imperial parade ground. Part of the feasibility of this location lay in the fact that it was a public health risk that needed cleaning up anyway: often muddy, it was a hazard to cross and a breeding ground for infestations particular to swamps. Locating the primary object of civic pride on such a site was daunting, but it had potential because of its size and location near the city core, home of Vienna's royal and aristocratic legacies.

Announcement in 1868 of the design competition for the new city hall elicited an international response, with sixty-four entries from France, Germany, Italy, and Austria. In October the following year, the jury selected a scheme coded as Saxa Loquuntor, or "the rocks are speaking," and named its German designer, Friedrich von Schmidt (1825–91), the winner. Designed in 1868–69 and constructed between 1872 and 1883, the new Rathaus was finally completed with furnishings in 1888.

Schmidt wanted his rocks to say something specific: his goal was to have civic architecture "speak" on behalf of the citizenry with the propriety of the religion he espoused. Born a Protestant in Frickenhofen, Württemberg, Schmidt had attended trade school in Stuttgart. His apprenticeship as a stonemason included fourteen years of work on the renovation and expansion of Cologne Cathedral under its supervising architects and, more important, its ideological backer, August Reichensperger. He became a member of Reichensperger's Cologne Circle, a group in close allegiance with similar contemporary pro-Gothic associations in England.

In 1858, after converting to Catholicism, Schmidt moved to Milan and became a professor at the Milan Academy. But the next year, because of the outbreak of war between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont, he moved to Vienna, arriving with the reputation of being one of Germany's most notable practitioners of the neo-Gothic. With the support of Emperor Franz Josef and Count Leo Thun-Hohenstein, the pro-Gothic education minister, he was appointed professor at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, the most prestigious school of art and architecture in the empire and its only institution at that time to offer instruction in architectural design.

Schmidt brought to this prestigious post an ideological position supporting neo-Gothic architecture as espoused in Reichensperger's Cologne Circle. While Gothic architecture was traditionally seen as a sacred idiom, the Cologne Circle...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für When Buildings Speak: Architecture as Language in the...

When Buildings Speak. Architecture as Language in the Habsburg Empire and Its Aftermath, 1867 - 1933. SIGNED DEDICATION BY THE AUTHOR.

Anbieter: Antiquariat Willi Braunert, München, Deutschland

4°, paperback. 326 pp Very fine copy. Sprache: Englisch Gewicht in Gramm: 0. Artikel-Nr. 23715

Gebraucht kaufen

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar