Verwandte Artikel zu Years With Laura Diaz Pa

Inhaltsangabe

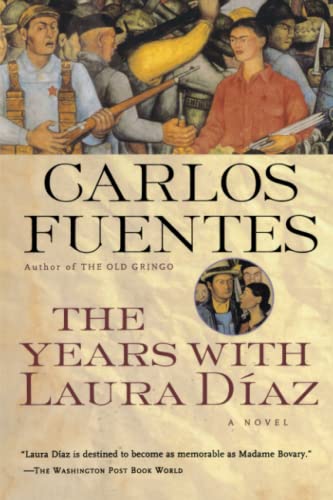

A radiant family saga set in a century of Mexican history, by one of the world's greatest writers.

Carlos Fuentes's hope-filled novel sees the twentieth century through the eyes of Laura Diaz, a woman who becomes as much a part of our history as of the Mexican history she observes and helps to create. Born in 1898, this extraordinary woman grows into a wife and mother, becomes the lover of great men, and, before her death in 1972, is celebrated as a politically committed artist. A complicated and alluring heroine, she lives a happy life despite the tragedies and losses she experiences, for she has borne witness to great changes in her country's life, and she has loved and understood with unflinching honesty.

In his most important novel in decades, Carlos Fuentes has created a world filled with brilliantly colored scenes and heartbreaking dramas. The result is a novel of subtle, penetrating insight and immense power.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Years with Laura Diaz

By Carlos FuentesHarvest/HBJ Book

Copyright © 2001 Carlos FuentesAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780156007566

Chapter One

Detroit: 1999

I knew the story. What I didn't know was the truth. In a way,my very presence was a lie. I came to Detroit to begin a televisiondocumentary on the Mexican muralists in the United States.Secretly, I was more interested in capturing the decay of a great city?thefirst capital of the automobile, no less, the place where Henry Fordinaugurated mass production of the machine that governs our livesmore than any government.

One proof of the city's power, we're told, is that in 1932 it invitedthe Mexican artist Diego Rivera to decorate the walls of the DetroitInstitute of Arts. And now, in 1999, I was here?officially, of course?tomake a TV series on this and other Mexican murals in the UnitedStates. I would begin with Rivera in Detroit, then move on to Orozco atDartmouth and in California, and then to a mysterious Siqueiros inLos Angeles, which I was instructed to find, as well as lost works byRivera himself: the mural in Rockefeller Center, obliterated becauseLenin and Marx appeared in it; and other large panels which had alsodisappeared.

This was the job I was assigned. I insisted on beginning in Detroitfor one reason. I wanted to photograph the ruin of a great industrialcenter as a worthy epitaph for our terrible twentieth century. I wasn'tmoved either by the moral in the warning or by any apocalyptic tastefor misery and deformity, not even by simple humanitarianism. I'm aphotographer, but I'm neither the marvelous Sebastião Salgado nor thefearsome Diane Arbus. I'd prefer, if I were a painter, the problem-freeclarity of an Ingres or the interior torture of a Bacon. I tried painting.I failed. I got nothing out of it. I told myself that the camera is thepaintbrush of our age, so here I am, contracted to do one thing butpresent?with a presentiment, maybe?to do something else very different.

I got up early to take care of my business before the film team setup in front of Diego's murals. It was 6 a.m. in the month of February. Iexpected darkness. I was ready for it. But its duration sapped myenergy.

"If you want to do some shopping, if you want to go to a movie, thehotel limo can take you and pick you up," they told me at the receptiondesk.

"But the center of town is only two blocks from here," I answered,both surprised and annoyed.

"Then we can't take any responsibility." The receptionist gave me apracticed smile. His face wasn't memorable.

If the guy only knew that I was going farther, much farther, thanthe center of town. Though I didn't know it yet, I was going to reachthe heart of this hell of desolation. Walking quickly, I left behind thecluster of skyscrapers arranged like a constellation of mirrors?a newmedieval city protected against the attacks of barbarians?and it tookme only ten or twelve blocks to get lost in a dark, burned-out wastelandof vacant lots pocked with scabs of garbage.

With each step I took?blindly, because it was still dark, becausethe only eye I had was my camera, because I was a modern Polyphemuswith my right eye glued to the Leica's viewfinder and my left eyeclosed, blind, with my left hand extended forward like a police dog,groping, tripping sometimes, other times sinking into something Icould smell but not see?I was penetrating into a night that was notonly persisting but being reborn. In Detroit, night was born fromnight.

I let the camera drop onto my chest for an instant, I felt the dullblow over my diaphragm?two diaphragms, mine and the Leica's?andthe sensation was repeated. What surrounded me was not the prolongednight of a winter dawn; it wasn't, as my imagination wouldhave me believe, a nascent darkness, disturbed companion of the day.

It was permanent darkness, the unexpected darkness of the city, itscompanion, its faithful mirror. All I had to do was turn right aroundand see myself in the center of a flat, gray lot, adorned here and therewith puddles, fugitive paths traced by fearful feet, naked trees blackerthan this landscape after a battle. In the distance, I could see spectral,broken-down Victorian houses with sagging roofs, crumbling chimneys,empty windows, bare porches, dilapidated doors, and, from timeto time, the tender and immodest approach of a leafless tree to a grimyskylight. A rocking chair rocked, all by itself, creaking, reminding me,vaguely, of other times barely sensed in memory ...

Fields of solitude, withered hill, my schoolboy memory repeatedwhile my hands picked up my camera and my mental hand went fromsnap to snap, photographing Mexico City, Buenos Aires if it weren't forthe river, Río if it weren't for the sea, Caracas if it weren't a shithole,Lima the horrible, Santa Fe de Bogotá losing its faith, holy or otherwise,Santiago with no saint to cure it. I was photographing the futureof our Latin American cities in the present of the most industrial cityof all, capital of the automobile, cradle of mass production and theminimum wage: Detroit, Michigan. I made my way shooting all of it,old, abandoned jalopies in lots even more abandoned, sudden streetspaved with broken glass, blinking lights in shops selling ... sellingwhat?

What could they be selling on the only illuminated corners in thisimmense black hole? I walked in, almost dazzled by the light, to buy asoda at one of those stands.

A couple almost as ashen as the day stared at me with a mix ofmockery, resignation, and malign hospitality, asking me, What do youwant? and answering me, We've got everything.

I was a little dazed, or it might have been habit, but I ordered, inSpanish, a Coke. They laughed idiotically.

"Stands like this, we only sell beer and wine," said the man. "Nodrugs."

"But lottery tickets we do sell," added the woman.

I got back to the hotel by instinct, changed my shoes, which weredripping all the waste of oblivion, and was just about to take my secondshower of the day when I checked my watch. The crew would be waitingfor me in the lobby, and my punctuality signaled not only my prestigebut also my discipline. Slipping on my jacket, I looked out at thelandscape from the window. A Christian city and an Islamic city coexistedin Detroit. Light illuminated the tops of skyscrapers and mosques.The rest of the world was still sunk in darkness.

We, the whole team, reached the Institute of Arts. First we crossedthe same unending wasteland, block after block of vacant lots, here andthere the ruin of a Victorian mansion, and at the end of the urbandesert (actually right in its heart) a structure in kitschy pompier stylefrom the early years of the century, clean and well preserved, spaciousand accessible by means of wide stone stairways and tall doors of steeland glass. It was like a memento of happiness in a trunkful of misfortunes,an old lady, erect and bejeweled, who has outlived her descendants,a Rachel without tears. The Detroit Institute of Arts.

The enormous central courtyard, protected by a high skylight, wasthe setting for a flower show. It was there the crowds were gatheringthat morning. Where'd they get the flowers? I asked a gringo in ourteam; he answered by shrugging his shoulders and not even glancing atthe plethora of tulips, chrysanthemums, lilies, and gladiolas displayedon the four sides of the patio?which we crossed with a speed that boththe team and I imposed on ourselves. Television and movies are thekind of work you want to get away from fast, as soon as quitting timecomes. Unfortunately, those who live on such work can imagine nothingelse to do with their lives but to go on filming one day after anotherafter another ... we're here to work.

Here he was. Rivera, Diego, Diego María of Guanajuato, DiegoMaría Concepción Juan Nepomuceno de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta yRodríguez, 1886-1957.

Pardon me for laughing. It's a good kind of' laugh, an irrepressibleguffaw of recognition and perhaps of nostalgia. For what? I think forlost innocence; for faith in industry; for progress, happiness, and historyjoining hands thanks to industrial development. To all those gloriesRivera had sung praise, as you'd have to in Detroit. Like the anonymousarchitects, painters, and sculptors of the Middle Ages who builtand decorated the great cathedrals to praise God ..... one, everlasting,indivisible?Rivera came to Detroit as pilgrims long ago went to Canterburyand Compostela: full of faith. I also laughed because this muralwas like a color postcard of the black-and-white setting for Chaplin'smovie Modern Times. The same machines, smooth as mirrors, the perfect,implacable meshing of gears, the confidence-inspiring factoriesthat Rivera the Marxist saw as an equally trustworthy sign of progressbut that Chaplin saw as devouring jaws, swallowing machines, like ironstomachs gobbling up the worker and at the end expelling him like apiece of shit.

Not here. This was the industrial idyll, the reflection of theimmensely rich city Rivera saw during the 1950s, when Detroit gavejobs and a decent life to half a million workers.

How did the Mexican painter see them?

There was something strange in this mural, with its teeming activityand spaces crowded with human figures working at shining serpentine,unending machines like the intestines of a prehistoric animal thatwas taking a long time to slouch back toward the present age. It alsotook me a long time to locate the source of my own surprise. I had a displacedand exciting sensation of creative discovery?very rare in televisionwork. Here I am in Detroit, standing in front of a mural byDiego Rivera because I depend on my audience just as Rivera, perhaps,depended on his patrons. But he made fun of them, he planted red flagsand Soviet leaders right in the very bastion of capitalism. On the otherhand, I wouldn't deserve either the censure or the scandal: the audiencegives me success or failure, nothing more. Click. The idiot box turns off.There are no more patrons, and what's more no one gives a fuck. Whoremembers the first soap opera they ever saw?or, for that matter, thelast?

But that sensation of surprise in front of such a well-known muralwouldn't let me alone or let me film as I wanted. I scrutinized things. Iused the pretext of wanting the best angle, the best light. Techies arepatient. They respected my efforts. Until I figured it out: I'd been lookingwithout seeing. All the American workers Diego painted have theirbacks to the spectator. The artist painted only working backs, exceptwhen the white workers are using goggles to protect themselves fromsparks thrown by the welding torches. The American faces are anonymous.Masked. Rivera saw them the way they see us, Mexicans. Withtheir backs turned. Anonymous. Faceless. Rivera wasn't laughing then,he wasn't Charlie Chaplin, he was only a Mexican who dared to say,None of you has a face. He was the Marxist who told them, Your workhas neither the worker's name nor his face, your work is not your own.

In contrast, who is looking out at the spectator?

The blacks. They do have faces. They had faces in 1932, whenRivera came to paint and Frida checked into Henry Ford Hospital, andthe great scandal was a Holy Family that Diego introduced into themural ostensibly as a provocation, although Frida was pregnant andlost the child and instead of a child gave birth to a rag doll and the baptismof the doll was attended by parrots, monkeys, doves, a cat, and adeer ... Was Rivera mocking the gringos or did he fear them? Was thatwhy he didn't paint them facing the world?

The artist never knows what the spectator knows. We know thefuture, and in that mural of Rivera's, the black faces that do dare tolook outward, who did dare to look at us, had fists and not only to buildFord's cars. Without knowing it, by pure intuition, Rivera in 1932painted the blacks who on July 30, 1967?the date is burned into theheart of the city?set fire to Detroit, sacked it, shot it to pieces, reducedit to ashes, and delivered forty-three bodies to the morgue. Were thosethe only people who looked out from the mural, those forty-threefuture dead men painted by Diego Rivera in 1932 and killed in 1967,ten years after the death of the painter, thirty-five years after beingpainted?

A mural only appears to disclose itself at a glance. Actually, itssecrets require a long, patient look, an examination which does notwear itself out, not even in the space of the mural, but which extendsto all those who prolong it. Inevitably, the mural's context renders thegaze of the figures eternal, along with that of the spectator. Somethingstrange happened to me. I had to direct my own gaze outside themural's perimeter in order to return violently?the way a movie cameracan move like an arrow from a full shot to a brutal close-up, to thedetail?to the faces of the women workers, masculinized by their shorthair and overalls but, no doubt of it, feminine figures. One of them isFrida. But her companion, not Frida but the other woman in the painting?heraquiline features, consistent with her large stature, hermelancholy eyes with shadows under them, her lips thin but sensual intheir very thinness, as if the fugitive lines of her mouth were proclaiminga superiority that was strict, sufficient, unadorned, sober, andinexhaustible, abounding in secrets when she spoke, ate, made love ...

I looked at those almost golden eyes, mestizo, between Europeanand Mexican, I looked at them as I'd looked at them so often in a forgottenpassport found in a trunk as outdated as the document itself. I'dlooked at them just as I had at other photos hung up, scattered around,or put away all over the house of my young father, murdered in October1968. Those eyes my dead memory didn't recognize but my livingmemory retained in my soul decades later, now that I'm about to turnthirty and the twentieth century is about to die; trembling, I stared atthose eyes with an almost sacred consternation which lasted so longthat my team stopped, gathered around?was something wrong withme?

Was something wrong with me? Did I remember something? I wasstaring at the face of that strange beautiful woman dressed as a worker,and as I did, all the forms of recollection, memory of whatever you callthose privileged instants of life, poured into my head like an oceanwhose unleashed waves are always yet never the same: it's the face ofLaura Díaz I've just seen; the face revealed in the hurly-burly of themural is that of one woman and one woman only, and her name isLaura Díaz.

The cameraman, Terry Hopkins, an old?even if young?friend,gave the painted wall a final illumination, filtered through blueaccents, perhaps as an act of farewell (Terry is a poet), for his lightingblended in perfectly with the real sunset of the day we were livingthrough in February 1999.

"Are you crazy?" he asked. "You're walking back to the hotel?"

I don't know what kind of look I gave him, but he didn't say anotherword. We separated. They packed up the annoying (and expensive)film equipment. They went off in the van.

I was left alone with Detroit, a city on its knees. I started walkingslowly.

Free, with the fury of a teenage onanist, I began to take pictures inall directions, of black prostitutes and young black policewomen, ofblack boys wearing ragged woolen caps and thin jackets, of old peoplehuddled around a garbage can turned into a street fireplace, of abandonedhouses?I felt I was getting inside all of them?the misérableswith no refuge, junkies who injected themselves with pleasure andscum in corners, I photographed all of them insolently, idly, provocatively,as if I were traveling down a blind alley where the invisible manwasn't any of them but me, I myself suddenly restored to the tenderness,nostalgia, affection of a woman whom I never in my life met butwho had filled my life with all those kinds of memory that are bothinvoluntary and voluntary, both a privilege and a danger: memoriesthat are simultaneously expulsion from home and return to the maternalhouse, a fearsome encounter with the enemy and a longing for theoriginal cave.

A man with a burning torch ran screaming through the halls of theabandoned house, setting fire to everything that would burn. I was hiton the back of my neck and fell, staring up at an upside-down, solitaryskyscraper under a drunken sky. I touched the burning blood of a summerthat still hadn't come, I drank the tears that won't wash away thedarkness of someone's skin, I listened to the noise of the morning butnot its desired silence, I saw children playing among the ruins, I examinedthe prostrate city, offering itself for examination without modesty.My entire body was oppressed by a disaster of brick and smoke, theurban holocaust, the promise of uninhabitable cities, no man's home inno man's city.

I managed to ask myself as I fell if it were possible to live the life ofa dead woman exactly as she lived it, to discover the secret of her memory,to remember what she would remember.

I saw her, I will remember her.

It's Laura Díaz.

Continues...

Excerpted from The Years with Laura Diazby Carlos Fuentes Copyright © 2001 by Carlos Fuentes. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Gebraucht kaufen

Zustand: BefriedigendEUR 8,19 für den Versand von USA nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenEUR 11,56 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für Years With Laura Diaz Pa

The Years with Laura Diaz

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1 Harvest. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 313738-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Years with Laura Diaz

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1 Harvest. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. GRP47852173

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Years with Laura Diaz

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.55. Artikel-Nr. G0156007568I4N00

Anzahl: 3 verfügbar

The Years with Laura Diaz

Anbieter: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Artikel-Nr. mon0003682379

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Years with Laura Diaz

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Artikel-Nr. P02N-00758

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Years with Laura Diaz

Anbieter: LiLi - La Liberté des Livres, CANEJAN, Frankreich

Zustand: very good. vendeur pro, expedition soignee en 24/48h.Le livre peut montrer des signes d'usure dus à son utilisation, etre marque ou presenter plusieurs dommages esthetiques mineurs. Artikel-Nr. 2104000002984

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Years with Laura Diaz

Anbieter: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Brand New. reprint edition. 516 pages. 9.00x6.00x1.00 inches. In Stock. Artikel-Nr. x-0156007568

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar