Inhaltsangabe

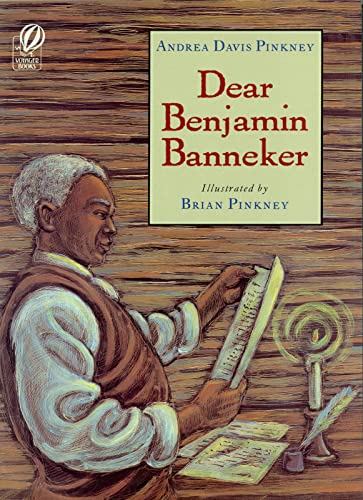

Throughout his life Banneker was troubled that all blacks were not free. And so, in 1791, he wrote to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who had signed the Declaration of Independence. Banneker attacked the institution of slavery and dared to call Jefferson a hypocrite for owning slaves. Jefferson responded. This is the story of Benjamin Banneker--his science, his politics, his morals, and his extraordinary correspondence with Thomas Jefferson. Illustrated in full-page scratchboard and oil paintings by Caldecott Honor artist Brian Pinkney.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorinnen und Autoren

Andrea Davis Pinkney is the New York Times best-selling author of several books for young readers, including the novel Bird in a Box, a Today Show Al Roker Book Club for Kids pick, and Hand in Hand: Ten Black Men Who Changed America, winner of the Coretta Scott King Author Award. Additional works include the Caldecott Honor and Coretta Scott King Honor book Duke Ellington, illustrated by her husband, Brian Pinkney; and Let It Shine: Stories of Black Women Freedom Fighters, a Coretta Scott King Honor book and winner of the Carter G. Woodson Award. Andrea Davis Pinkney lives in New York City.

Brian Pinkney is a celebrated picture-book illustrator who has won two Caldecott Honors. His professional recognition includes the Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award and three Coretta Scott King Illustrator Honors. He has collaborated with his wife, author Andrea Davis Pinkney, on several picture books including Duke Ellington: The Piano Prince and His Orchestra and Sleeping Cutie. The Pinkneys live in Brooklyn, New York.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Dear Benjamin Banneker

By Andrea Davis Pinkney, Brian PinkneyHoughton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

All rights reserved.

Contents

Title Page,

Table of Contents,

Copyright,

Dedication,

Author's Note,

Dear Benjamin Banneker,

About the Author,

About the Illustrator,

CHAPTER 1

No slave master ever ruled over Benjamin Banneker as he was growing up in Maryland along the Patapsco River. He was as free as the sky was wide, free to count the slugs that made their home on his parents' tobacco farm, free to read, and to wonder: Why do the stars change their place in the sky from night to night? What makes the moon shine full, then, weeks later, disappear? How does the sun know to rise just before the day?

Benjamin's mother, Mary, grew up a free woman. His daddy, Robert, a former slave, gained his freedom long before 1731 when Benjamin was born. Benjamin Banneker had official papers that spelled out his freedom.

But even as a free person, Benjamin had to work hard. When Benjamin grew to be a man, he discovered that to earn a decent living he had little choice but to tend to the tobacco farm his parents left him, a grassy hundred acres he called Stout.

Benjamin worked long hours to make sure his farm would yield healthy crops. After each harvest, Benjamin hauled hogshead bundles of tobacco to sell in town. The work was grueling and didn't leave him much time for finding the answers to his questions about the mysterious movements of the stars and cycles of the moon.

But over the course of many years, Benjamin managed to teach himself astronomy at night while everyone else slept.

There were many white scientists in Benjamin's day who taught themselves astronomy and published their own almanacs. But it didn't occur to them that a black man — free or slave — could be smart enough to calculate the movements of the stars the way Benjamin did.

Benjamin wanted to prove folks wrong. He knew that he could make an almanac as good as any white scientist's. Even if it meant he would have to stay awake most nights to do it, Benjamin was determined to create an almanac that would be the first of its kind.

In colonial times, most families in America owned an almanac. To some, it was as important as the Bible. Folks read almanacs to find out when the sun and moon would rise and set, when eclipses would occur, and how the weather would change from season to season. Farmers read their almanacs so they would know when to seed their soil, when to plow, and when they could expect rain to water their crops.

Beginning in 1789, Benjamin spent close to a year observing the sky every night, unraveling its mysteries. He plotted the cycles of the moon and made careful notes.

The winter of 1790 was coming. In order to get his almanac printed in time for the new year, Benjamin needed to find a publisher quickly. He sent his calculations off to William Goddard, one of the most well-known printers in Baltimore. William Goddard sent word that he wasn't interested in publishing Benjamin's manuscript. Benjamin received the same reply from John Hayes, a newspaper publisher.

Benjamin couldn't find a publisher who was willing to take a chance on him. None seemed to trust his abilities. Peering through his cabin window at the bleak wintry sky, Benjamin's own faith in his almanac began to shrivel, like the logs burning in his fireplace.

Finally, in late 1790, James Pemberton learned of Benjamin Banneker and his almanac. Pemberton was the president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, a group of men and women who fought for the rights of black people. Pemberton said Benjamin's almanac was proof that black people were as smart as white people. He set out to help Benjamin get his almanac published for the year 1791.

With Pemberton's help, news about Benjamin and his almanac spread across the Maryland countryside and up through the channels of the Chesapeake Bay. Members of the abolitionist societies of Pennsylvania and Maryland rallied to get Benjamin's almanac published.

But as the gray days of December grew shorter and colder, Benjamin and his supporters realized it was too late in the year 1790 to publish Benjamin's astronomy tables for 1791. Benjamin would have to create a new set of calculations for an almanac to be published in 1792.

Benjamin knew many people would use and learn from his almanac. He also realized that as the first black man to complete such a work, he'd receive praise for his accomplishment. Yet, Benjamin wondered, what good would his almanac be to black people who were enslaved? There were so many black people who wouldn't be able to read his almanac. Some couldn't read and were forbidden to learn. Others, who could read, had masters who refused to let them have books. These thoughts were never far from Benjamin's mind as he worked on his 1792 almanac.

Once his almanac was written, Benjamin realized he had another task to begin. On the evening of August 19, 1791, Benjamin lit a candle and sat down to write an important letter to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. The letter began:

Maryland, Baltimore County, Near Ellicott's Lower Mills August 19th. 1791. Thomas Jefferson Secretary of State.

Sir, I am fully sensible of the greatness of that freedom which I take with you on the present occasion; a liberty which Seemed to me Scarcely allowable, when I reflected on the distinguished, and dignifyed station in which you Stand; and the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so previlent in the world against those of my complexion.

Years before, in 1776, Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, a document that said "all men are created equal." But Thomas Jefferson owned slaves. How, Benjamin wondered, could Thomas Jefferson sign his name to the declaration, which guaranteed "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness" for all? The words Thomas Jefferson wrote didn't match the way he lived his life. To Benjamin, that didn't seem right.

Benjamin knew that all black people could study and learn as he had — if only they were free to do so. Written on the finest paper he could find, Benjamin's letter to Thomas Jefferson said just that. His letter reminded Thomas Jefferson that, at the time of the American Revolution when he was struggling against British tyranny, he had clearly seen the right all men have to freedom:

Sir how pitiable is it to reflect, that altho you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of those rights and privileges which he had conferred upon them, that you should at the Same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my bretheren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the Same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others, with respect to yourselves.

Along with his letter, Benjamin enclosed a copy of his almanac.

Eleven days later, Benjamin received a reply from Thomas Jefferson. In his letter, Jefferson wrote that he was glad to get the almanac and that he agreed with Benjamin, black people had abilities that they couldn't discover because they were enslaved. He wrote:

Philadelphia, Aug. 30. 1791.

Sir, I Thank you sincerely for your letter of the 19th instant and for the Almanac it contained. No body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Dear Benjamin Banneker

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Reprint. It's a well-cared-for item that has seen limited use. The item may show minor signs of wear. All the text is legible, with all pages included. It may have slight markings and/or highlighting. Artikel-Nr. 0152018921-8-1

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Very Good condition. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Artikel-Nr. J06A-03517

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 8 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0152018921I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 5 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0152018921I3N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0152018921I3N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0152018921I3N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0152018921I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 12 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0152018921I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0152018921I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Dear Benjamin Banneker

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Pinkney, Brian (illustrator). Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0152018921I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar