Inhaltsangabe

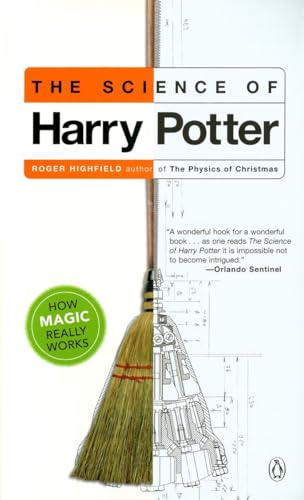

Behind the magic of Harry Potter—a witty and illuminating look at the scientific principles, theories, and assumptions of the boy wizard's world, newly come to life again in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child and the upcoming film Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald

Can Fluffy the three-headed dog be explained by advances in molecular biology? Could the discovery of cosmic "gravity-shielding effects" unlock the secret to the Nimbus 2000 broomstick's ability to fly? Is the griffin really none other than the dinosaur Protoceratops? Roger Highfield, author of the critically acclaimed The Physics of Christmas, explores the fascinating links between magic and science to reveal that much of what strikes us as supremely strange in the Potter books can actually be explained by the conjurings of the scientific mind. This is the perfect guide for parents who want to teach their children science through their favorite adventures as well as for the millions of adult fans of the series intrigued by its marvels and mysteries.

• An ALA Booklist Editors' Choice •

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorinnen und Autoren

Dr. Roger Highfield is science editor of The Daily Telegraph, which has published several thousand of his articles since 1986. A regular broadcaster on the BBC and the winner of several journalism awards, Highfield is the author ofThe Physics of Christmas and coauthor of such highly acclaimed books as The Arrow of Time and The Private Lives of Albert Einstein.

Roger Highfield was born in Wales, raised in north London and became the first person to bounce a neutron off a soap bubble. He was the science editor of The Daily Telegraph for two decades and the editor of New Scientist between 2008 and 2011. Today, he is the Director of External Affairs at the Science Museum Group. A regular broadcaster on the BBC and the winner of several journalism awards, Highfield is the author of The Physics of Christmas and coauthor of such highly acclaimed books as The Arrow of Time and The Private Lives of Albert Einstein.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Broomsticks, Time Travel

and Splinching

"The Bludgers are up!" yells the commentator. In the airborne stadium with golden goalposts, two teams of seven players zoom around on broomsticks, swooping and weaving as they dodge their opponents' missiles-Bludgers-while trying to score with the red Quaffle. The game of Quidditch enthralls the broomstick-riding Harry, who tries to catch the Golden Snitch and win the game for Gryffindor House.

The wizarding world's favorite form of transport, the broomstick, is one of its worst-kept secrets, for every Muggle knows that witches and wizards use them to get about. Even now, scientists and engineers are trying to figure out how they do so. The most prized of racing broomsticks, the Nimbus 2000 and the Firebolt, probably use extremely advanced technology to defy the tug of Earth's gravity, a technology that has massive commercial and scientific implications. Researchers from NASA would sell their grandmothers to obtain Harry's broomstick, not to mention Hover Charms, Mr. Weasley's enchanted turquoise Ford Anglia, the flying motorbike that Hagrid borrowed from Sirius Black, or the candles that hover in the Great Hall of Hogwarts, all of which suggest that witches and wizards must know how to turn gravity on and off at will.

Exotic materials that can produce antigravity could also pave the way to wormholes, hypothetical shortcuts between two widely separated points in space-time. You could, for example, step into one end of a wormhole and emerge from the other a million miles away, 10,000 years in the past. There are several episodes in the Harry Potter books where wizards travel through a shortcut to Platform Nine and 3/4, or to visit the Diagon Alley wizard shopping arcade. Maybe they made these quick trips by wriggling through wormholes.

Enchanted travel opportunities do not end there. Harry used Floo powder to flit about. Other objects and people can appear out of thin air, whether the Knight bus, the food that fills plates at mealtimes, or a wizard clutching an old boot. Such remarkable materializations could be due to exotic technology, perhaps similar to that used in Star Trek to beam members of the Enterprise down to the surface of alien planets. Today, the possibility of such extraordinary feats taking place can be glimpsed when properties of atoms have been shuffled around the laboratory by practitioners of a leading-edge field called quantum teleportation.

The Quest to Fly with Broomsticks

It is a dream that is as old as humanity: to step out into thin air and fly like a bird, to cast off the bonds of gravity, to soar free, zooming through the clouds with the wind rustling past our outstretched and rapidly flapping arms.

Why, then, can't we fly? The short answer is that we are not birds. The longer one is that the human body is unable to deliver the right combination of thrust and lift. The longest answer I intend to give is that we lack feathers to help generate lift and propulsion, efficient lung design, large enough hearts, hollow bones to reduce our weight, and adequate muscle power to generate a sufficient flap.

While we cannot fly unaided, a broomstick is not as preposterous a form of transport as it sounds. Even NASA has pronounced on broomstick propulsion: A considered overview of the various technologies on offer has been put together by Mark Millis, who has the impressive title of project manager for the Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Project at the NASA Glen Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio.

Millis began with the oldest technology, a balloon-assisted broomstick. This does not seem like a particularly promising contender for Harry's wooden steed. First, a blimplike construction would seem unlikely to achieve the Firebolt's quoted performance of zero to 150 mph in ten seconds. (That's fast, although a fraction of the performance of a 6,000-horsepower dragster, which can cover a quarter-mile from a standing start in less than five seconds to reach 320-plus mph.) Millis also points out that balloon-based vehicles would make easy targets for Bludgers.

How about an airplane-style broom? Intriguingly, this suggestion is more magical than it may at first seem. A century after the Wright brothers made their first flight, Jef Raskin, a former professor at the University of California at San Diego and the inventor of the Macintosh computer, says that the usual popular textbook explanations for what keeps aircraft aloft are wrong.

Aircraft fly because air travels faster over the top surface of each wing than underneath. A theory by Dutch-born Daniel Bernoulli established that this speed difference produces a drop in air pressure over the top of the wing, which generates lift. (You can demonstrate this effect at home by blowing between two dollar bills.) But there is a problem, says Raskin. "The naive explanation attributes the lift to the difference in length between the curved top of a wing and the flat bottom of the wing. If this were true, planes could not fly upside down, for then the curve would be on the bottom and the flat on the top." But planes can fly upside down, and not only do some wings have the same curve on top and bottom, but even flat-winged paper airplanes can take to the skies.

The key question remains: How do wings generate lift? Robert Bowles of University College London, a mathematician with expertise in aerodynamics, agrees with Raskin that lift occurs when the flow of air around a wing is turned downward. When flow is deflected in one direction, lift is generated in the opposite direction, according to Newton's third law of motion. However, for a wing, it is crucial to understand that the downward flow depends on air being both deflected by the underside of the wing and bent by the topside.

The latter is trickier to visualize. Because air is slightly viscous it tends to stick to the top of the wing and can generate whirling masses of air called vortices. You can see this effect by adding a dash of milk to black coffee and moving a spoon through it, revealing how movement through such a "sticky" fluid generates a coffee vortex. As vortices are shed by the top surface of a wing, the flow turns downward to generate an upward force on the wing.

With the right equipment, you could detect a force on your spoon as you move it through the coffee, says Bowles. This force-the same as the one that keeps a wing aloft-depends on the angle of attack and the shape of the spoon. Mathematical models show that even flat wings can fly if they have an angle of attack to deflect air downward. As for planes flying upside down, the lift can remain positive even if the angle of attack is negative, because of the shape-a stretched teardrop-of the wing.

Although this "airfoil theory" is now standard in books on mathematical fluid mechanics, some mysteries of flight remain. How to capture the essence of turbulence (when air flow is disorderly), in a computer or clever mathematical formula has in no way been mastered by even the best Muggle scientists. Turbulence is generated to some degree by all forms of flight through air. Next time you board an aircraft, just remember that a little magic helps to keep you aloft.

Wings mark a conventional solution to the broomstick problem, and one that would be a good way to build up frequent-flyer miles, though it may be easy to lose your luggage, remarked Millis, a not entirely serious answer. Save a mention of the Slytherin team whizzing through the air like jump jets, however the many references to swooping and soaring on brooms contain no suggestion of wings, engines, or any such equipment. Harry must sit on exotic technology.

How about a rocket-assisted broom? This is an entirely feasible solution, but a stick thus outfitted could be tricky to steer and, given the long robes that wizards wear, something of a fire hazard. Which brings us to the...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Very Good condition. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Artikel-Nr. O11D-02387

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 3 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Reprint. It's a well-cared-for item that has seen limited use. The item may show minor signs of wear. All the text is legible, with all pages included. It may have slight markings and/or highlighting. Artikel-Nr. 0142003557-8-1

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0142003557I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0142003557I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0142003557I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Artikel-Nr. G0142003557I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter : How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. 3128402-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter : How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Artikel-Nr. GRP88639180

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: WeBuyBooks, Rossendale, LANCS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. A copy that has been read but remains in clean condition. All of the pages are intact and the cover is intact and the spine may show signs of wear. The book may have minor markings which are not specifically mentioned. Artikel-Nr. rev7555021384

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works

Anbieter: WeBuyBooks, Rossendale, LANCS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Very Good. Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. A copy that has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Artikel-Nr. rev3774460436

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar