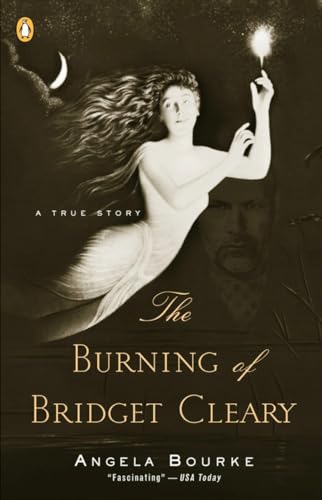

Verwandte Artikel zu The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Inhaltsangabe

In 1895, Bridget Cleary, a strong-minded and independent young woman, disappeared from her house in rural Tipperary. At first her family claimed she had been taken by fairies-but then her badly burned body was found in a shallow grave. Bridget's husband, father, aunt, and four cousins were arrested and tried for murder, creating one of the first mass media sensations in Ireland and England as people tried to make sense of what had happened. Meanwhile, Tory newspapers in Ireland and Britain seized on the scandal to discredit the cause of Home Rule, playing on lingering fears of a savage Irish peasantry. Combining historical detective work, acute social analysis, and meticulous original scholarship, Angela Bourke investigates Bridget's murder.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Angela Bourke is senior lecturer in Irish at University College, Dublin. She has been a visiting professor at Harvard University and the University of Minnesota and writes, lectures, and broadcasts on Irish oral tradition and literature.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Burning of Bridget Cleary

A True StoryBy Angela BourkePenguin Books

Copyright © 2001 Angela BourkeAll right reserved.

ISBN: 0141002026

Chapter One

Laborers, Priests, and Peelers

The winter of 1894/95 was exceptionally hard, with February1895 the coldest yet recorded in many parts of Ireland and Britain.Farm work was seriously delayed, and agricultural laborers in Irelandwere facing unemployment and destitution. In mid-March, though,both weather and economic prospects improved. It was a time ofrecord keeping and centralized bureaucracy. At Birr Castle Observatoryin King's County, as Offaly was then called, Robert Jacob keptscrupulous twice-daily weather records, which he entered by handon large printed sheets supplied by the Meteorological Office inLondon. On April 2, 1895, in accordance with instructions printedon the form, he folded his March return four times to make a letter-sizedpacket, stuck on a red halfpenny stamp showing the head of ayounger Queen Victoria, and sent it off. The back of the form hadalready been printed with the address: 63 Victoria Street, London. Itarrived there on April 4, postmarked "Parsonstown 6.50 Ap 2 95."

According to Jacob's records, the temperature at Birr Castle atnine o'clock in the morning, Wednesday, March 13, had been 37.4degrees Fahrenheit; twenty-four hours later it had risen to 50.5. By9 o'clock on Thursday evening the weather was still mild and dry,with a temperature of 46.8. Fifty miles away, on a farm at Kishogue,near the village of Drangan, County Tipperary, Michael Kennedyasked his employer, Edward Anglin, for his wages, and set out on athree-mile walk along dark roads to give the money to his widowedmother. Mary Kennedy lived in a tiny, mud-walled, thatched housebeside Ballyvadlea bridge, where Michael and his brothers and sisterhad grown up. When he got there, however, she was on her wayout. Her twenty-six-year-old niece Bridget Cleary had been ill forseveral days, and Mary Kennedy was going to visit her for the secondor third time. Michael Kennedy decided to follow his mother to hiscousin's house, across the bridge and up the hill. Bridget lived onlyhalf a mile away, with her husband, Michael Cleary, a cooper, andher father, who was Mary Kennedy's brother.

The Clearys lived in a slate-roofed laborers' cottage, built a fewyears earlier; though modest, it was a much better house than MaryKennedy's, or indeed than many others in the area. When MichaelKennedy arrived there on the night of Thursday, March 14, it wasfull of people and activity. His cousin's illness seemed to have reachedsome kind of crisis. In the kitchen, where a group of neighborswaited, some green stumps of whitehorn were burning slowly in thefire grate, and a large oil lamp stood on the table. Just off the kitchen,Bridget Cleary lay in the front bedroom, where the only light camefrom a candle. Her bed almost filled the tiny room, but several menwere standing around it, holding her down; another was lying acrossher legs.

Most of the men in the bedroom were Bridget Cleary's relatives,among them Michael Kennedy's brothers, Patrick, James, and William.The others were her husband Michael, her father PatrickBoland, and a cousin of his called Jack Dunne. A teenage boy, WilliamAhearne, was with them, holding the candle. The men were tryingto make Bridget Cleary swallow herbs boiled in new milk?MichaelCleary was holding a saucepan and a spoon?but she was resistingthem. Again and again, as though they doubted her identity, they demanded,in the name of God, that she say whether or not she was indeedBridget Cleary, daughter of Patrick Boland and wife ofMichael Cleary. The men were shouting as they questioned her andforced the mixture into her mouth. Eventually they lifted her out ofbed and carried her through the door to the kitchen fire, abouttwenty feet away. There they questioned her again, holding her overthe smoldering wood as they demanded that she answer her name.The neighbors who were in the kitchen heard them talk aboutwitches and fairies.

When Bridget Cleary's death was being investigated in the weeksthat followed, Michael Kennedy claimed not to remember muchabout the events of that evening. In Clonmel Prison, seven monthslater, it was noted that he had been tubercular ("phthisical") for years.He may also have had epilepsy, for he told the court that he was susceptibleto fits, and that he had lost consciousness in the crowded andnoisy house. When he woke up, he said, he was lying in bed in thesecond small bedroom at the back of the house, where his uncle,Patrick Boland, usually slept. He believed he had been unconsciousfor at least half an hour.

The house was quiet again by the time he woke. Bridget Clearywas in bed, and apparently resting, but at some point during theevening word had come that her husband's father had died. MichaelCleary was not from Ballyvadlea, but from Killenaule, about eightmiles away, and several of the men were preparing to walk there toattend his wake. Wakes were all-night affairs, and major social eventsfor the rural working class, with storytelling, games, and other amusements;they were prime occasions for the exchange of terrifying legendsabout ghosts and fairies, and for young men and women tomeet. Patrick, James, and William Kennedy had wanted to go earlier?theyhad spent part of the evening shaving each other in theback bedroom in preparation?but Michael Cleary had delayed themby demanding that they stay and assist him with his wife's treatmentuntil after midnight. Michael Cleary himself might have been expectedto go to Killenaule, if only to see his bereaved mother, but heinsisted on staying at home with his wife. Old-style wakes were increasinglyfrowned on by respectable society, and Michael Cleary wasbetter educated than most of his wife's relatives; still, his decision notto attend his own father's wake was surprising.

Michael Kennedy's older brother Patrick was thirty-two, Michaelhimself was twenty-seven, James was twenty-two, and Williamtwenty-one. All were farm laborers and unmarried, and only theyounger two could read or write. They left the house in Ballyvadleatogether at about one o'clock in the morning to walk to Killenaule.Eight miles was a considerable distance, but the night was fine andmen of their class were used to walking. The moon had been fullthree nights earlier, and had been up for over an hour by the timethey set out, so they would have had no difficulty in finding theirway. Several women and a few of the other men remained in thehouse for the rest of the night, carrying drinks to Bridget Cleary asshe called for them. It was not unusual for people to stay up very latelike this, talking and swapping stories, when they visited neighbors:the Irish word airneán, which has no precise equivalent in English,means just this sort of gathering.

The moon was high in the sky at about three in the morningwhen the Kennedys arrived at the wake. Their sixty-six-year-old uncle,Patrick Boland, joined them there even later. After a few hours,he returned to Ballyvadlea, where his daughter still lay ill, but thefour Kennedys stayed all the next day in Killenaule. They walkedback together as far as Drangan on Friday evening, then Patrick,James, and William continued home to their mother's house at Ballyvadleabridge, while Michael returned to Anglin's farm at Kishogue.

Saturday, March 16, was warm and sunny, but as MichaelKennedy walked from Kishogue back into Drangan village, a shockawaited him. Thirty-six hours earlier, he had seen his cousin BridgetCleary ill in bed in Ballyvadlea, but now he was told that she had disappearedfrom her home. More disturbing still was the suggestionthat she had gone across the fields with two men in the middle of theprevious night, wearing only her nightdress. Some people were evensaying plainly that the fairies had taken her away.

Despite his protestations about having fainted in his cousin'shouse, Michael Kennedy must have known something of the treatmentshe had received on Thursday evening. According to the kindof stories often told at firesides and at wakes, certain illnesses weresupposed to be the work of the fairies, who could abduct a healthyyoung person and leave a sickly changeling instead: herbal medicinesand ordeals by fire were both said to be ways of banishing such achangeling.

In Drangan, Michael Kennedy spent a while outside Feelys' groceryshop and spoke to two men named Burke and Donovan, but hecould get no further information. He had begun to walk back towardAnglin's farm when he met the two men most likely to know thetruth, Michael Cleary and Jack Dunne. Dunne had been one of themen gathered around Bridget Cleary's bed on Thursday night. Hewas Mary Kennedy and Patrick Boland's first cousin, and lived nearBallyvadlea, in the townland of Kylenagranagh.

Cleary and Dunne were both agitated when Michael Kennedymet them in the street, a little after midday. In fact Michael Clearyseemed distraught. He was wearing a suit of light gray tweed?jacket,waistcoat, and trousers?and a navy-blue cap, but his clotheshad greasy marks and hung loosely, as though they were too big forhim, and when Kennedy spoke to him he made no answer. Ignoringthe younger man's questions, he kept on walking toward the largeCatholic church in the center of the village, while Jack Dunnelimped along behind. Dunne, according to his own later account, wasgravely concerned about Cleary. Cleary had been talking wildlyabout strange men, and burning, and had threatened to cut his ownthroat, so Dunne had persuaded him to come to Drangan to talk tothe priest. When Michael Kennedy could get no reply from either ofthe men, he turned and followed them, and together the three enteredthe chapel yard.

Drangan is a quiet village in the beautiful and fertile green rollingfarmland of County Tipperary's South Riding, about fifteen milesnortheast of Clonmel, and seven from the medieval walled town ofFethard. When the census was taken in 1891, it had 34 houses, and apopulation of 127. The village has one street, which begins wherethe road from Fethard enters from the southwest. Mullinahone is fourmiles to the east, but the main road between the two towns passes farthersouth, through the village of Cloneen. Drangan lies surroundedby hills, on the edge of the Slieve Ardagh range, roughly at the centerof a quadrangle of major roads whose northern corners are at Killenauleand Ballingarry. It is a natural meeting place for a scatteredrural population, at the head of a small valley which runs down toMullinahone, but its importance is strictly local.

By far the most imposing building in Drangan is the chapel, asCatholic churches are usually called in rural Ireland. It stands on thenorth side of the main street, squarely in the center of the village,surrounded by graves dating from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.High iron railings and gates separate it from the street outside,and a plaque announces its dedication in 1850 to the ImmaculateConception of the Virgin Mary.

In the years following Catholic Emancipation in 1829, "bigchapels" like this one steadily replaced the humble buildings in whichCatholics had previously worshipped. The earliest were rectangularand strictly functional, but by 1895, large, costly, and elaborately decoratedcruciform buildings in towns and villages proclaimed the socialand economic importance of the Catholic Church and its clergy.Drangan chapel was built of cut stone between 1850 and 1853, andDrangan, whose shops and houses flank it and look up to it, is a classicexample of what has been called a "chapel-village," where theconstruction of a big chapel in the countryside in the nineteenthcentury generated the growth of other services, including the stateapparatus of police station and post office.

When Michael Kennedy, Michael Cleary, and Jack Dunne enteredthe chapel yard at about one o'clock, Michael McGrath, thefifty-nine-year-old parish priest of Cloneen and Drangan, was inthe church. The Synod of Thurles in 1850 had laid down rules forthe administration and regulation of Catholic practice in Ireland, reinforcingthe Church's control of its members' daily lives. The Synodwas the first formal meeting of the Irish bishops since 1642, andmany of its prescriptions were designed to centralize religious activityin church buildings, and put an end to the tradition of administeringthe sacraments in private homes. The Synod had decreed thatconfessions should be heard regularly in all churches, and the faithfulencouraged to attend the sacrament weekly; so on March 16, 1895,Fr. McGrath was hearing confessions. His curate, or coadjutor, CorneliusFleming Ryan, known as "Father Con" was also in the chapel.Not only was this the day before St. Patrick's Day, it was a feast of theImmaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, to whom the buildingwas dedicated.

Jack Dunne went into the building alone. Like Michael Kennedyand his brothers, he was a farm laborer. A short, fat, gray-haired manwho walked with a pronounced limp, he was described in contemporaryaccounts as old, although records show that he was fifty-fivein 1895. The same pattern emerges again and again among the documentsof this story, as people in their fifties and sixties, if they belongto the laboring class, are described as "old." Accounts of theirphysical appearance reflect the hardships and privations of working-classlife in nineteenth-century Ireland, especially for those born beforethe Famine of 1845-49. Jack Dunne could read, but not write.He was missing several teeth; his eyesight was poor, and a fracture hadleft his right leg shorter than his left.

Michael Kennedy stayed in the yard with the still-agitatedMichael Cleary, while Dunne went into the chapel. Cleary, beardedand balding, looked older than his thirty-five years. He was easily themost educated of the three, able to read and write, and possessor of askilled trade, for he was a cooper, a maker of the casks and barrels inwhich commodities of all kinds, both wet and dry, were stored andtransported. Before coming to live with his wife and her father,Michael Cleary had worked for several years in Clonmel, and he hadbuilt up a lucrative trade of his own since moving to Ballyvadlea. Ashe waited outside the chapel, however, he was weeping and distressed.Michael Kennedy stood awkwardly beside him.

In the chapel, Jack Dunne made his way to where Fr. McGrathwas hearing confessions. When Fr. McGrath had listened to Dunne'sstory, he told him to send Michael Cleary in at once to speak to him.

Michael Cleary, still crying, went into the chapel, but instead ofgoing to speak to Fr. McGrath, he approached the altar. There theyounger of the parish's two priests, Fr. Con Ryan, found him kneeling,tearing out his hair and, as he put it later, behaving like a madman.Cleary seemed to be suffering, Fr. Ryan said, from remorse forsomething he had done, and wanted to go to confession, but the curatedid not think he was "in a fit state to receive the sacrament" andasked him instead to come into the vestry. Fr. Ryan began to feelafraid of him then, however, and coaxed him back out into the yard,where Jack Dunne and Michael Kennedy were waiting. Cleary wasstill crying loudly.

Fr. Ryan moved toward Dunne, gesturing to Michael Cleary toleave him. "Go on," he said, according to Dunne's memory; "'tis thisman I want to be talking to." Throughout the evidence given later tothe magistrates at Clonmel Petty Sessions, and again before a judgeand jury at the summer assizes, witnesses who could not write toldtheir stories with considerable dramatic use of direct speech.

The priest addressed Jack Dunne as Michael Kennedy took Clearyaside. "What's up with him?"

Dunne told him that Cleary had claimed to have burned his wifethe previous night, and that three or four people had buried her. "I'vebeen asking them all morning to take her up and give her a Christianburial."

Fr. Ryan had visited Bridget Cleary in her home only the day before.He was horror-struck: "How could three or four of them goout of their minds simultaneously?" he wondered in his evidence.His impression, he said, had been that Michael Cleary's mind was goingastray. "He's in a bad way," he told Dunne. "It would be better tosee after him [to do something about him]. We'll see the parishpriest."

Fr. McGrath had come out of the chapel into the yard, and theyounger priest went to speak to him. Jack Dunne watched the twopriests talking, then both he and Michael Kennedy saw Fr. Ryancross the street and go into the constabulary barracks.

In 1895, as now, Drangan's architecture proclaimed the importanceof Catholicism in the life of rural Ireland, its centrality in the village,and the authority of its priests. In 1895, it also demonstrated the delicatebalance between the church and a very different, equally centralizedauthority.

The "Peelers," called after their founder, Sir Robert Peel, livedand worked in the Royal Irish Constabulary barracks in Drangan.RIC men were the eyes, ears, and often the arms, of the British administration,based in Dublin Castle. Their training and disciplinewere military and, unlike other police forces in the United Kingdom,they were armed. They were engaged in surveillance of known or suspectedsubversives, but also had considerable civil and local governmentresponsibility, to the extent that by the end of the nineteenthcentury their duties had become "more akin to house-keeping thanto peace-keeping" and they rarely carried firearms. Their positioncould still be ambiguous, however: their work did not endear themto the tenant farmers and shopkeepers, who constituted the increasinglynationalist Irish Catholic middle class, even though over 70percent of the men recruited to the force after 1861 were Catholic.In the 1880s, members of the RIC were boycotted in County Tipperary,especially during the operation of the repressive "coercion"legislation, during and after the Land War of 1879-82.

With a history of nationalist politics and agrarian conflict, CountyTipperary's South Riding had the highest police presence of anycounty in Ireland in the 1890s: 47 per 10,000 of population, comparedwith the lowest figure of 12 each in the northern counties ofDerry and Down, or 34 and 38 in North Tipperary and Meath respectively.According to the census of 1891, 7 district inspectors, 10head constables, and 454 sergeants, acting sergeants, and constablescomprised the force in South Tipperary.

A road guide published in 1893 for the use of members of theconstabulary gives a flavor of the world in which the RIC was operating.The agrarian disturbances and "outrages" that had characterizedthe Land War and its aftermath had largely ceased, althoughoccasional incidents were still reported. Members of the constabularyhad leisure to become proficient riders of bicycles: a new sport andmode of transport until recently available only to the gentry. The authoracknowledges the help he has received from all ranks of theRIC, including "the junior constable, who, perhaps an enthusiasticcyclist, did his utmost to place his local knowledge at the service ofthe public." The book includes, among advertisements for corn cures,fishing tackle, insurance, and whiskey, several for bicycles, pneumatictires, and cycling clothes, as well as for publications devoted to cycling.Intended for "the overcoat pocket, or the hand-bag of thetourist," this work was undertaken "with the view of supplying agreat want of the Royal Irish Constabulary, and of kindred publicservices; and also of providing a `Road Book' of a reliable and comprehensivecharacter, for the use of cyclists and tourists, of Irish travellersand others of the public who may desire to travel through ourbeautiful island."

"Each Police Barrack in Ireland," the guidebook begins, "is thecentre of a circle of `Circumjacent' Stations. Each Police Station hassent in a return, on identical lines, giving similar information as regardsitself and circumjacent neighbouring Police Barracks which areprinted in uniform style and sequence." Reduced to a system of abbreviations,each entry details the facilities available in the vicinity ofa barracks: post, telegraph, and money-order offices, with theiropening hours and times of delivery and collection; horse-drawn"post-cars" for hire; nearest railway station; markets, court sittings,and places of interest or beauty, if any. (None is listed for Drangan orCloneen, although Fethard has several.) Directions to each of the"circumjacent" stations are given as part of every entry, with distancescalculated to within a quarter of a mile. Every road mentionedis classified from A ("level broad roads, on which two four-wheeledvehicles can trot abreast") to D ("up and down hill, and narrow"),with a description of its condition, ranging from G[ood] or F[air], toI[ndifferent] or R[ocky and rutty].

Standardization and uniformity were hallmarks of nineteenth-centuryofficial thinking, gradually imposed throughout the countryside:police officers, soldiers, railway employees, and postmenwore uniform clothing, which immediately identified them; worksof literature were published in identical bindings in uniform editions;administrators at every level of society filled out printed forms andreturned them by post to central offices for filing; trains ran accordingto printed timetables, and standard time was gradually adoptedeven in the most remote areas. In Ireland, as elsewhere in Europe,these were the symptoms of profound cultural change. As the Englishlanguage replaced Irish throughout most of the country during thesame period, oral tradition gave way to print. A whole world ofwakes, herbal cures, stories of kings and heroes, and legends of thefairies?the culture of those who had not learned to read and write?becameincreasingly marginal. Jack Dunne, Michael Kennedy, hisolder brother Patrick, and several others in this story, were amongthose people. They still lived in a symbolic universe very differentfrom the one mapped by the RIC: centralization and uniformity hadlittle relevance to their daily lives.

Even priests wore uniform in late-nineteenth-century Ireland. Bydecree of the Synod of Thurles, and partly as a strategy for safeguardingclerical celibacy, black clerical garb, including the Romancollar, had become standard for Catholic priests, who were also orderedto avoid undue familiarity with women. The Catholicism thepriests propounded in the towns and chapel villages of County Tipperarywas modern minded, outward looking, literate, and essentiallymiddle class. It sternly opposed attendance at wakes, and had no timewhatever for stories about fairies. Highly centralized, with priests reportingto bishops, and bishops reporting to Rome, the church inIreland was strongly influenced by Continental practice, especiallythe Marian devotions favored increasingly by the papacy in this period.The dedication of Drangan Chapel to the Immaculate Conception,four years before Rome defined that doctrine as dogma, wastypical. Since 1870, the church hierarchy's authority had beenstrengthened by the declaration of papal infallibility, but such teachinghad little effect on the landless, or on their oral culture. Folk religionwas centered on holy wells, local saints, the kin-group, and thehome, rather than on church buildings, and its teachings were transmittedthrough traditional prayers, songs, and stories, not throughprinted catechisms. Well into the twentieth century, this kind of uncentralizedCatholicism, which sat more easily with unofficial traditionsabout a fairy supernatural than the official version could, wasstill strong in places where Irish was spoken.

Most Catholic priests in Tipperary in the late nineteenth centurywere drawn from the increasingly prosperous class of English-speakingtenant farmers. Many held leases on farms of their own, and lived atleast as well as the better-off farmers to whom they ministered. Althoughthe five, seven, or more years they spent in seminary trainingcould not be described as a liberal education, it equipped them totake the lead in a society where schooling and literacy were steadilyadvancing. Many were involved in the politics of the Land League(1880-81), and of the Irish National League that succeeded it: mostof the National League's ninety-six branches were centered onCatholic chapels.

The RIC monitored the activities of the Land League and theNational League, and reported regularly on the movements of themany priests known to be politically active. By 1895, the politicalpower of priests was less than it had been, and land agitation had dieddown, but Michael McGrath, parish priest of Drangan, had a historyof political involvement, and his activities were still of interest to themembers of the constabulary stationed across the street from his church.

Continues...

Excerpted from The Burning of Bridget Clearyby Angela Bourke Copyright © 2001 by Angela Bourke. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

EUR 3,44 für den Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenGratis für den Versand innerhalb von/der Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: Bahamut Media, Reading, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Artikel-Nr. 6545-9780141002026

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I3N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I5N00

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I5N00

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I3N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I4N00

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I5N00

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I3N00

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I5N00

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Burning of Bridget Cleary: A True Story

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.56. Artikel-Nr. G0141002026I3N00

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar